After the 2016 election when millions of Americans were thrown into existential free-fall, one could almost hear the gnashing of teeth as the defeated decried the incoming president as a man of low moral character, unbefitting the highest office in the land. The assertions were numerous and quite a sight to behold. America was tearing itself apart and democracy with it. In short, everything was awful.

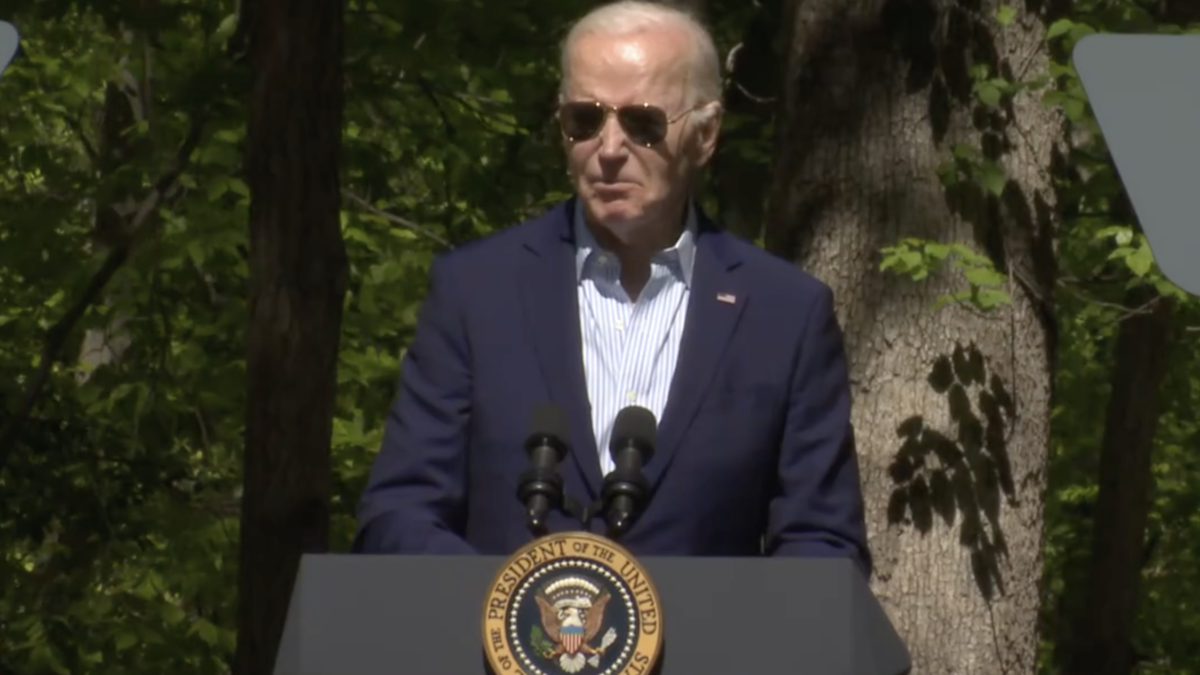

Since then, there has been a spate of articles addressing how to talk to your children — some are even pretty decent. Talking to our kids about our misgivings regarding political leaders is a good thing. Indeed, I fully expect we’ll all have numerous discussions with our children about President-elect Joe Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris. My concern, however, is that we make sure not to project our anxieties and fears onto our children in doing so.

While it’s OK for our children to see us as human beings who sometimes enter periods of distress, we must be careful not to behave in a way that leaves them overly prone to being distressed. We saw versions of this when we had reports of school children responding in terror to Donald Trump as president.

Parents and caregivers teach kids by example how to regulate fear. Frankly, it’s a travesty that over the last four years, too many children were taught to live in fear for their lives because Trump was president.

Replicating that kind of mental abuse in 2021 or taking cheap shots at Biden’s character is equally unhelpful. There is, however, an appropriate way to talk to our children about legitimate concerns for our republic.

Of the many techniques to address apprehensions about a new political leader, teaching fear isn’t one of them. If you’re one of the millions of parents out there seeking counsel on how to talk about Biden and his upcoming administration to your children without damaging them, there’s good news, and there’s bad news.

Let’s start with the bad news, since it’s never good to end on a downer. Your concern is well-founded. Biden is unlikely to fix the reality that our children will live in a much more challenging and dysfunctional America than we did, and to what degree his presidency improves things is debatable.

Conversely, we, Generation X and older, could take as fact that the executive, judicial, and legislative branches of our government, although imperfect, would generally protect our constitutional rights. We could trust we were a government for the people and by the people. We held as immutable that we are all created equal with certain inalienable rights given to us by God. There was a reasonable expectation that our government would responsibly adhere to the principles of democracy such as majority rule with minority rights.

The systemic erosion of the foundational institutions of our government has been ongoing for quite some time, however. A canon of scholarly work is dedicated to identifying the precise moment America started to go downhill. Suffice it to say, while I’m unwilling to chuck the republic whole cloth, by Biden’s own admissions, certain parts of our government and daily life will become imperiled by his presidency, such as forcing both sexes into intimate spaces, forcing taxpayers to sponsor abortion, and eroding our rights to free speech.

So that’s the bad news, and this assessment is probably understating the damage that will be done. Yet I believe there’s still hope — which brings us to the good news.

The good news is, we as parents and caregivers, have a lot of influence over who our children will be, and by extension, the nation they inherit as they grow into adults. Kids will do what we do more often than what we say. And we’re created to have rich and full lives informed by our biological, psychological, social, and spiritual needs.

The first step to discussing the implications of this election is to make sure your children are observing responsive, emotionally mature, and regulated behavior from you.

Like I told my friends after Trump was elected, take this opportunity to model the behaviors your child needs to be resilient in times of uncertainty. Don’t catastrophize everything — instead, be the well-grounded, constant adult.

This is especially true for younger children. Our kids need us to show them appropriate crisis management. They need to see that even when we’re afraid, we can still be OK.

If you’re a person of faith, this is the time to model how faith informs attitudes and behavior. It’s confusing for a child to hear you speak about the sovereign power of Jesus in times of uncertainty and trouble, but watch then subsequently watch you collapse under the weight of fear in times of uncertainty and trouble.

Children should never receive a tacit message from you that either “Some things are too big and bad for God to handle” or “Somethings are too big and bad for me to handle.” So be mindful of how you demonstrate your frustration, concern, and occasional anger. Our kids are always watching, and they’ll take the strategies they witness from you into their own adulthood.

Secondly, for parents of older children, it’s best to frame objections to Biden and his administration in the context of history, not as character assassination. Engaging in personal attacks may feel good at the time, but it ultimately harms us and ends up saying more about our character than Biden’s. It helps nothing and it greatly increases the risk our objectionable behavior will shut down the conversation. Kids don’t want to talk to us when we’re hostile and unreasonable.

Using history provides a thoughtful and reasoned framework from which to have your discussion. It’s an opportunity to examine the central tenets of what makes America exceptional and why we protect them. If your children are already versed in American history, your conversation may look more like the Socratic method wherein you challenge your kids to ask questions and think critically about the arguments.

Your children may disagree with you. That’s OK. Ultimately, they may even disagree with you on incredibly important things. That’s OK, as well. The point isn’t to indoctrinate your child by overpowering him and bending him towards your will. Rather, you’re demonstrating that while there are important historical reasons for your (sometimes) mercurial and animated expressions of concern, you can still be gracious and open to the free exchange of ideas.

By regulating our emotions when we’re distressed, and by speaking in respectful ways when we have a robust disagreement, we can lovingly reinforce that our children’s opinions matter, and deserve our respect.

When we have civil discourse — even about alarming threats to things we hold dear — we help produce adults who have civil discourse. Even better, we can play a role in shaping adults who don’t see the opposition as enemies but as inherently valuable fellow human beings deserving of being treated respectfully. If we do that, there will be reasons for hope after all.