Eddie was just four years old when his older brother Albert died. The youngest of 10 children, Eddie remembered the funeral well: The casket rested on a set of chairs in the front room of their simple farmhouse, while their congregation and pastor stood outside, behind the fence, near the road.

It was 1925 in rural Wentworth, South Dakota, and Eddie’s family was in quarantine. His sister, 9-year-old Ella, had diphtheria. Albert, 20, was the first in their family to receive the diphtheria vaccination. He died from the shot.

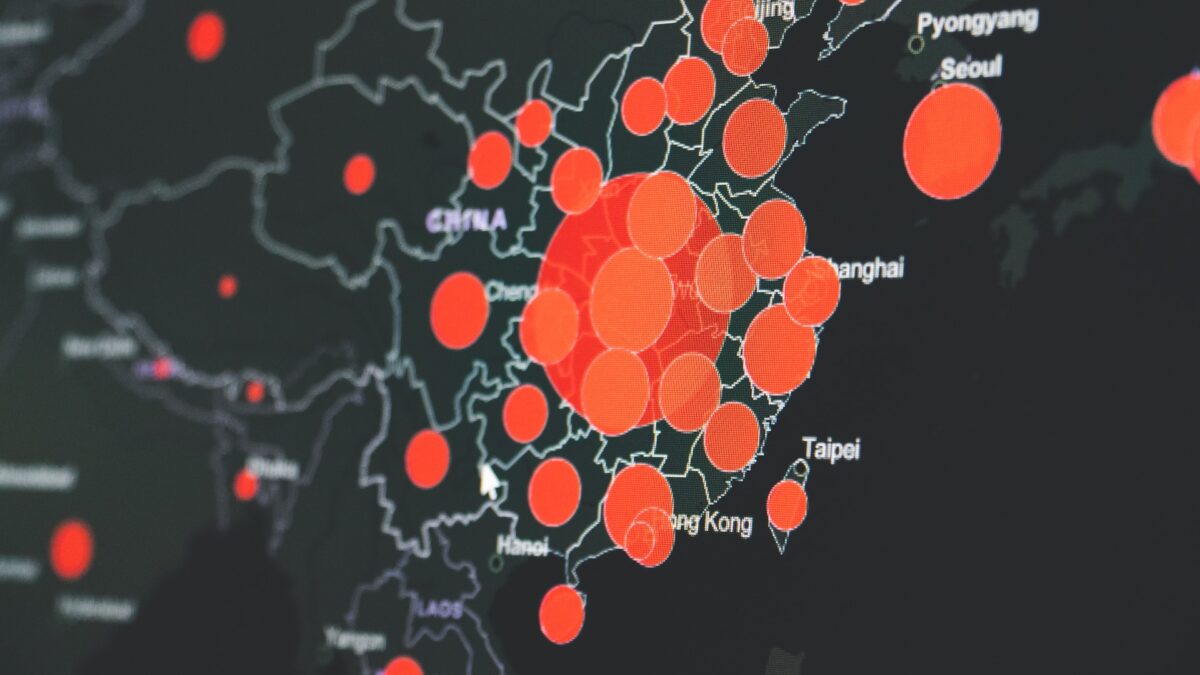

Some 94 years later, Eddie’s family and friends stood behind other “fences,” watching his funeral from a distance — for us, 685 miles — as it was live-streamed from a nearly empty church. We were in quarantine as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

A Zoom Funeral Isn’t At All Like Real Thing

Edward Robert Weerts, my husband’s father, died April 17, less than a month shy of his 99th birthday. He did not have COVID-19, but because of nationwide restrictions, we weren’t able to see him in the last weeks of his life at the senior care facility where he lived, nor attend his memorial service.

Instead, we joined family and friends electronically, an experience shared by thousands across the country during this time, as gathering sizes are limited at the grave, the church, and the funeral home.

My friend attended a memorial service through Zoom with about 700 others for a young mother who took her life. Another friend was one of 10 allowed at her mother-in-law’s graveside committal, where her four sons, their wives, the pastor, and the funeral director mourned. When a church mother from St. Paul Lutheran Church in Dallas died, only 10 could go to the grave, but the many members who cherished her stood at the cemetery at a distance, behind invisible fences.

We sat in our living room in Selma, Alabama, and tuned in to the memorial service at Ed’s Lutheran church in Fort Wayne, Ind. We could see the pastor and the altar with lit candles and altar cloths, a photograph of Edward, a box containing his ashes, and flowers. We could also see the back of the heads of my brother-in-law and his wife, who had lived near Ed and helped with his care. Many friends and family wanted to attend but were turned down. The magic number 10 was taken up by the quartet, organist, pastor, camera man, and three people from the congregation.

The liturgy was beautifully arranged with favorite hymns, prayers, and scripture readings, including Psalm 23 and Sunday’s gospel reading. It also incorporated his selected scripture, Ephesians 2:1-10, with verses that touch the heart of the Lutheran expression of faith: “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God.”

The pastor’s eulogy was thoughtful and theologically rich; he clearly knew Edward personally and of his dedicated life as a parochial school educator. Edward taught school and served as principal in Lutheran schools across the Midwest for more than 43 years. He also played organ and led Bible studies in church on Sundays.

During one of his last phone conversations with my husband, he was happy to tell him that he had finally caught up on tithes to his church. His strong Christian faith was the center of his life.

The service lasted about 40 minutes. I’m grateful the church had the capacity to live-stream it — my little country church does not — and that the pastor spoke with such wisdom and warmth. At the end was a photo montage of my father-in-law from various ages, mostly pictures with his beloved wife, Margaret, who passed the previous year. They were married 74 years and had four children.

Remembering Loved Ones Isn’t the Same in Isolation

Then it was over. We sat on our couch on a Monday afternoon miles away from “home” in a quiet, empty house. There were no hugs, no words of condolence. There were no stories, no favorite shared memories. No communal meal, prepared with love by the women of the church, and no shared laughter remembering our loved one — like the time he ran out of gas and uncharacteristically stopped to buy a six-pack of beer, or his endless “punny” jokes. “It’s raining cats and dogs out there. See all the poodles?”

The mourning of a loved one is best done with those who knew and loved him: family, friends, and church members. It’s hard to do alone.

No one seemed to expect how hard it would be. After the service, we heard from only one family member, one of my husband’s cousins. Sweet cards arrived in the mail, mostly from our friends in Alabama who never knew Ed, and couldn’t talk about his love of fishing in his small aluminum boat, his favorite red sweater, and how he won all the word games he played.

The first in his family to go to college, Ed got his teaching degree at Concordia Teacher’s College in Seward, Nebraska, where he met Margaret, who also was a Lutheran school teacher. Every summer, he went home to Wentworth to help his father combine for local farmers.

My husband remembered how his father’s analytical mind could plan bus routes for 300 students at the urban parochial school where he was principal. He set up the school lunch program, ordered books and supplies, hired teachers and staff, and attended all the school games while carrying a full teaching load. During summer “breaks,” he earned his master’s degree in administration, while raising his family and taking long drives back to Wentworth to see extended family.

COVID-19 Recalls a Past Quarantine

Every once in a while, the memory would return, of the ugly orange placard screaming “DANGER” across their farmhouse, and the surreal funeral of his beloved older brother that September day.

Diphtheria was a major cause of illness and death in the 1920s, especially for children. Between 1921 and 1925, about 15,529 people died from the disease. Characterized as “the Strangling Angel of Children,” diphtheria is a bacterial infection that causes swelling of the mucous membranes, including the throat, that can obstruct breathing and swallowing. It is highly contagious and can be spread by chronic carriers without knowing it. (Sound familiar?) Before treatment existed, the disease was fatal in up to half of cases.

The strict quarantine laws on the books in 1920 required a prominently displayed placard on the home once a member was diagnosed — a sign Ed remembered well, even though he had not yet learned to read. No family member was permitted to attend school, church, the theater, parties, picnics, or any other public gathering, eat in public places, drink from fountains, use public transportation, or enter public parks.

No food was to be given to the family in containers to be returned, nor was anyone to touch the same pencils, books, or clothing. The quarantine finally ended only when nose and mouth tests of all family members were clear.

By the mid-1920s, researchers had developed a vaccine against the disease, and infection rates dropped dramatically. In the 1940s, a combined diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine was developed that is still given today.

It was a cruel irony that Ed’s brother Albert died from the vaccine that would virtually eliminate the disease, while his sister Ella, the diphtheria patient, fully recovered. It is another irony that a traumatic childhood experience would be replayed decades later, in 2020, when everyone is quarantined, healthy or not.

During this season of shutdowns, families of the dead and the dying suffer a silent grief that lingers, unresolved. Like mourners behind the fence at the Weerts family farm in South Dakota, we leave the computer-projected memorial service in the disquieting silence with hurting hearts.