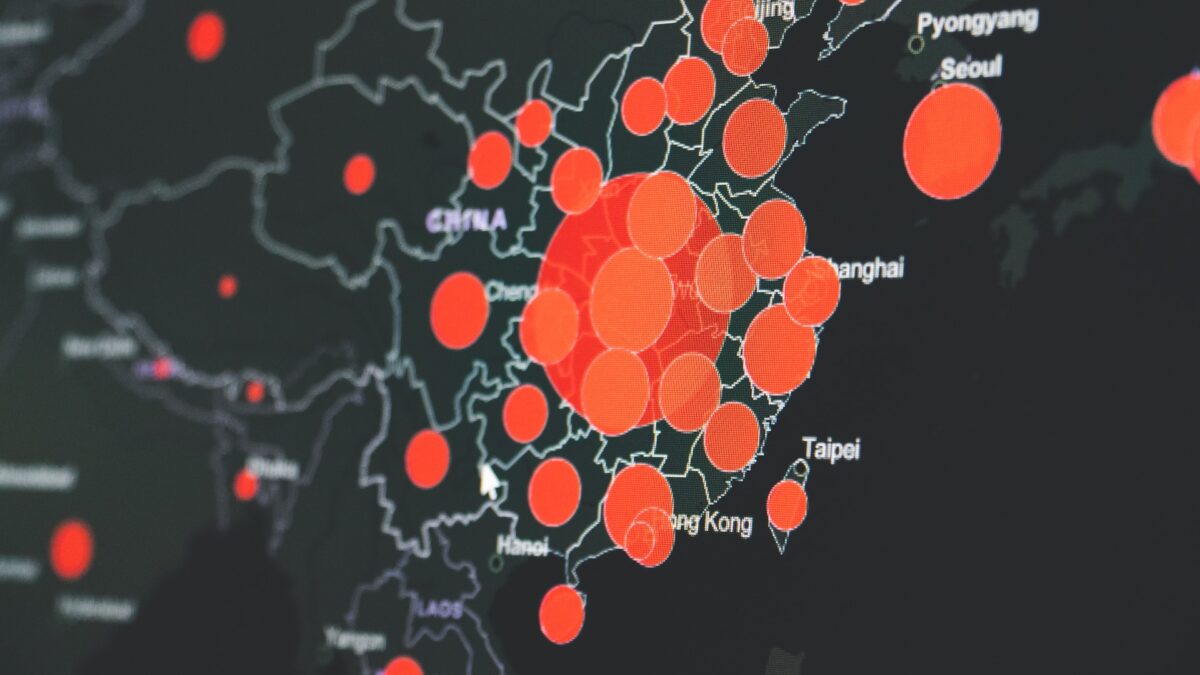

This week marks just over two months since most states instituted shelter-in-place orders to contain COVID-19, and with this milestone came an apparent turn in the tide of public opinion—or at least, public behavior—on social distancing.

Even as Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and one of President Trump’s most prominent pandemic advisors, warned against rolling back lockdown orders in his testimony to Congress on May 12, the return of warmer weather combined with “quarantine fatigue” compelled more and more people to return to pre-pandemic activities.

A recent study from Ipsos reported that since May a full third of Americans have visited friends or relatives, up from 19 percent in April. Whereas more than half of Americans (55 percent) reported “self-quarantining” last month, those numbers slid to 36 percent. Surveys from Kantar further revealed that as the spread of coronavirus slows, frustration has overtaken worry as Americans’ prevailing sentiment, and jobs have replaced health as the primary concern.

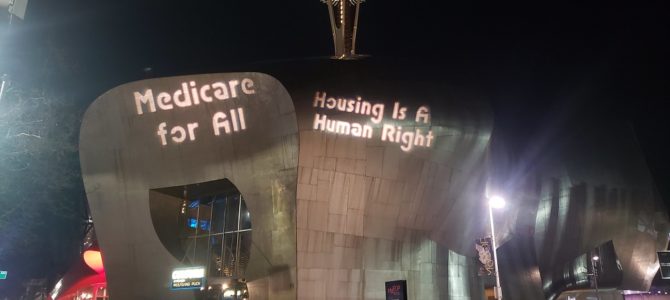

Regardless of where the masses lie on lockdowns, the decision to re-open local economies technically rests with government officials. While some are more aggressive in their re-opening strategy, such as Florida’s Gov. Ron DeSantis, many pro-quarantine politicians still err on the side of caution. Take Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan, who said, “it is still far too early to take our foot off the brake,” and “[every] one of us must continue physical distancing” to save lives.

But if local leaders prolong shelter-in-place rules with no end in sight, the ruinous social and economic consequences for individuals will inevitably harm American cities as suffering residents like me face little choice but to skip town in search of greener pastures.

The New, Virtual Reality

Three years ago I moved to Seattle from suburban Pennsylvania as a fresh-faced grad ready to take on the abundant opportunity promised by the city’s booming economy. Consistently ranked among the fastest-growing regions in the nation, Seattle is home to a slew of sexy start-ups and big tech firms, the influx of which has helped cultivate a diverse social scene and a bustling night life. These qualities, combined with the surrounding mountains and picturesque lakes characteristic of the Pacific Northwest, make the city an ideal locale for any twenty-something looking for a fresh start.

Yet the drastic changes wrought by the state’s response to coronavirus threaten the life many transplants have built. Since moving west, I’ve worked as a salesperson for a small corporate training company, picking up an additional part-time gig as a bartender in one of the city’s many restaurants. Given Seattle’s high cost of living, I’m dependent on both incomes to sustain my life here. As the pandemic reached emergency levels in March, I quickly lost my latter job as Washington suspended dine-in service.

While I consider myself lucky to retain my sales career, my future there is highly uncertain. As we sell a product often deemed non-essential by our clients, budgets allocated for services like ours are often first cut. Indeed, our revenue has plummeted. We’re surviving in large part due to government assistance provided by the payroll protection program in the CARES Act, but once those funds run out, the company will likely administer layoffs unless the economy rebounds quickly.

We’re hardly unique. “Non-essential” businesses large and small, such as Airbnb and Uber, have cut huge segments of their workforce, while others like BuzzFeed and TripAdvisor have scaled back or ceased global operations. To date, at least 46 percent of Americans are out of work and nearly 40 million have applied for unemployment benefits, numbers increasing each day. Despite these catastrophic statistics, major cities like Seattle have yet to alleviate the immense financial burden posed by ever-increasing rents, which continue to climb even amid the pandemic.

With no definitive timeline for re-opening, my company has ditched our pricey downtown workspace and transitioned to a permanently virtual organization. Industries have seen little-to-no decrease in productivity among their employees since shifting to remote work (in many cases experiencing quite the opposite), leading more and more companies to consider forsaking their expensive urban offices, which would reduce overhead while facilitating a healthier, more flexible employee experience.

A City Without a Soul

Jobs are often the magnet drawing people to cities, and with my company going virtual, I’m now anchored only by the other main metropolitan allure: its role as a cultural center and hub for entertainment, recreation, and social activity. But now this crucial function has also all but vanished, sacrificed at the #StayHomeSaveLives altar by our powerful municipal overlords.

Prior to COVID-19, my typical weekend might include a sojourn to the busy restaurants of Ballard, a popular North Seattle neighborhood, where my friends and I would bounce between local shops and bars before catching a show at a music venue or having a bonfire at a local park. Given the famously idyllic summers here, the rest of the weekend would likely entail a hike or camping trip to one of the hundreds of trails dotting the I-5 corridor.

For Seattleites, this is now a pipe dream. Although Gov. Jay Inslee has eased restrictions on a few outdoor activities like golfing and fishing, most recreation remains inaccessible, from closed-off camping sites and mountain access roads to shuttered gyms, sports leagues, and outdoor courts. Retail and entertainment, including farmer’s markets, movie theaters, and concert halls, have, of course, remained shut down.

Even if Inslee reopens Seattle restaurants, his phased approach only allows for 50 percent capacity, prohibits bar seating, and mandates employers log customer information such as phone numbers and email addresses—a profoundly intrusive measure sure to deter patrons. Indeed, these restrictions on public accommodations will not only hamper employers’ efforts to survive financially, but also effectively abolish crowded celebrations, events, and the lively social climate of pre-pandemic life.

Government officials’ histrionic warnings have also compelled many people I know to reject private social gatherings of any kind. While virtual happy hours and Jackbox games can be entertaining, they’re simply no replacement for the physical interaction humans desperately need.

As Washington and other states look poised to impose physical distancing measures until there is a vaccine, I ask myself: What is the point of living in a city devoid of the very things that distinguish it? Why spend an exorbitant amount to live a lonely, isolated life in Seattle, when I could maintain an equally unsatisfying existence, for far less, somewhere else?

Lockdowns Don’t Save Lives, They Trade Them

Inevitably, some folks will read this and think, “So what?” When we’re told by politicians and media that the most important thing is to do all we can to “save just one life,” what does it matter if people start deserting cities?

What’s missing is an acknowledgement of the tradeoffs. Two scholars from the Foundation for Economic Education, Dr. Anthony Davies and James R. Harrigan, recently noted that while most recoil at the mention of tradeoffs in a crisis, “each one of us balances human lives against dollars, and any number of other things, every day.” We don’t, for example, legally mandate exercise even though heart disease claims hundreds of thousands of lives each year, nor do we ban driving cars, which statistically carry much greater risk than driving SUVs.

So while public figures sound very noble in their commitment to save all lives from COVID-19 no matter the cost, this is an irrational and short-sighted way to craft policy. “The uncomfortable truth,” Davies and Harrigan conclude, “is that no policy can save lives; it can only trade lives.”

There have already been tremendous costs from lockdowns globally. Seriously ill patients can’t access critical care as hospitals limit their capacity; UNICEF predicts more than 1 million children under age five will die from preventable causes in the next six months.

Access to the outdoors and a vibrant social life are critical to mental health, yet after just two months of quarantine, calls to hotlines have surged by 900 percent. Increases in domestic violence and suicides nearly always accompany rises in unemployment, and as that figure is now broaching 15 percent, there is significant cause for concern.

I have not yet contracted the coronavirus, and while for that I am thankful, I can’t say for certain that state-sanctioned physical distancing is responsible. Because I’m young and maintain a healthy lifestyle, I’m naturally lower risk.

What I do know, however, is that in just two months, the state’s measures have already cost me a job, deeply fractured my community, and compromised my emotional well-being. This is something I’m not willing to endure indefinitely, and I know I’m not alone. Seattle, and America’s other major cities, must urgently re-evaluate their commitment to quarantine lest they drive away the very people who helped them flourish.