In the fluid pandemic situation, religious freedom is being tossed around, both as the basis for continuing public gatherings and as a focus of derision from those using the crisis to argue that religious people are the problem. Some defiant pastors have held large gatherings, while some government officials have threatened to permanently close churches that won’t comply with stay-at-home orders.

How would all these scenarios play out in a legal contest? There are basically three relevant rules:

- The current U.S. Supreme Court interpretation of the First Amendment dictates that a law limiting religious practice is allowed as long as it affects nonreligious practice in the same way.

- If a law or order singles out religious practice for disfavored treatment, that would be unconstitutional.

- In jurisdictions with more robust protections for religious liberty, such as Religious Freedom Restoration Acts (RFRAs), the government can’t create a burden on religious practice unless it has a compelling reason for doing so and the burden narrowly affects only the religious practices that interfere with the government’s compelling interest.

Do Louisiana and Florida Rules Violate Religious Freedom?

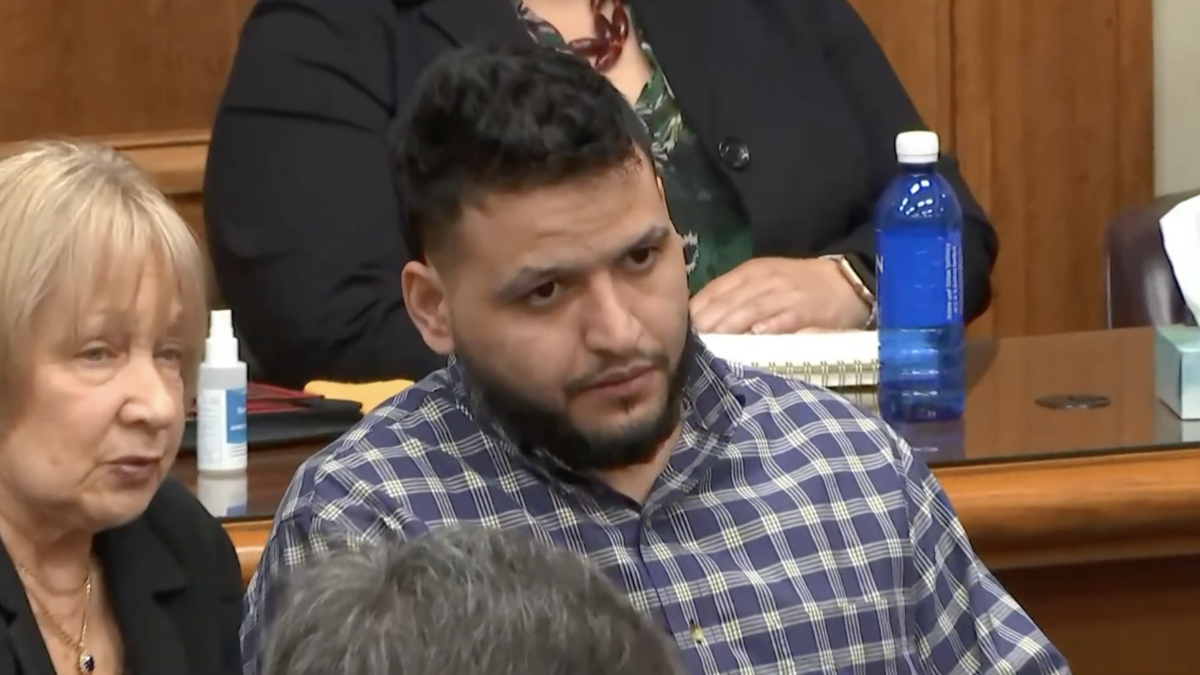

Thanks to the pandemic, we’re now looking at real-world examples. A Louisiana pastor is under fire for holding church services for hundreds of parishioners despite a state ban on large gatherings. His attorney argued that people “would rather come to church and worship like free people than live like prisoners in their homes” and then suggested that depression and anxiety experienced by people confined to their homes could be “worse than the people who have already contracted this virus and died.”

That’s not the only example. A Florida pastor was also arrested for holding large church services in defiance of an executive order meant to limit gatherings.

It’s important to note that these instances appear to be a small exception to the strong trend of religious groups canceling services to protect public health. In a recent survey, only 12 percent of regular church attendee respondents said that “in-person services at their house of worship have not been canceled.”

The relevant rules applying to defiant pastors will depend on the state involved. The most high-profile case was in Louisiana, which has a RFRA. So the legal analysis would address three questions:

- Does the decision to prevent religious gatherings create a burden on religious practice? The answer would appear to be yes.

- Does the government have a compelling reason for imposing the burden? Here the answer too would probably be yes. Preserving public health is a crucial public interest, so a broad prohibition on gathering meant to prevent the spread of communicable disease is probably fine.

- Is the burden as narrow as possible so as not to limit religious practice more than absolutely necessary? This is often the most difficult question, but given the demonstrated risk of gatherings, and since churches aren’t singled out, the answer here is likely yes as well.

Absent another factor, the preclusion of gatherings in Louisiana would probably be found not to be an unfair imposition on religious freedom.

In a different state that does not have an RFRA, the analysis is simpler. If the government bans all gatherings, religious and nonreligious, it is not singling out religious practice for discrimination, so the bans would be allowed under the controlling interpretation of the U.S. Constitution.

Do These Laws Meet a Compelling State Interest?

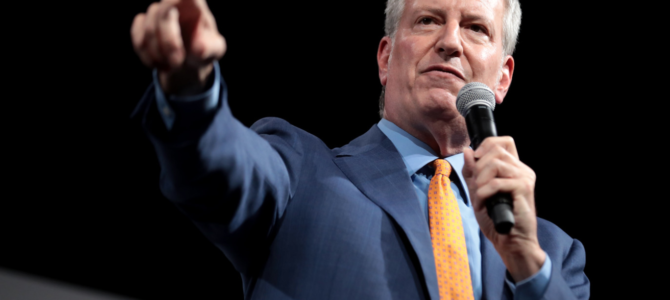

Now, let’s take an example on the other side. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio received harsh criticism when he made the ill-advised comment that churches that did not close down might be closed permanently. If de Blasio were really to try this, it would likely be held unconstitutional.

While protecting public health is a valid and probably compelling interest, a permanent ban is not the narrowest way to advance that interest. The city could probably prevent gatherings during the pandemic, but once the public health threat is over, the compelling reason for the regulation disappears.

These examples arguably represent extremes, so let’s look at another scenario that’s not as clear on its face. Imagine a situation wherein churches are not singled out because other similar organizations are closed, but bars or restaurants are allowed to stay open. This seems problematic because apparently similar activities are being treated differently, and since religion has formal constitutional protections, this seems unfair on its face.

The legal rules that apply to this scenario would depend on the controlling law. Under the low-protection rule (a non-RFRA state), the fact that religious groups are not singled out may be enough to make these distinctions valid. Under the high-protection rule (an RFRA state), the result could be different.

Like the analysis above, there is a burden on religious practice, and the government would have an interest in preventing the spread of the disease. Importantly, however, the differential treatment of apparently similar circumstances suggests the government is not tailoring its solution of closing churches as narrowly as it should to avoid burdening religious freedom. In that scenario, the government would need to show a justification for treating bars differently from churches, or the courts could decide the regulation doesn’t fit the government’s public health interest.

The Law Should Advance Safety and Freedom

Of course, it will take time to establish this through litigation. Some states are trying to avoid these conflicts entirely by recognizing the important spiritual needs of citizens while simultaneously limiting exposure to the virus.

For example, in Utah, Gov. Gary Herbert’s directive, asking the state to avoid gatherings of any size, includes an accommodation for religious leaders and workers to perform their necessary work and singles out workers “necessary to plan, record, and distribute online or broadcast content to community members.” This approach allows the use of technology to meet the need for religious services while still preventing gatherings that could spread the virus.

So in Louisiana and Florida, the courts would likely rule that the states can limit religious gatherings. In New York, the court would almost certainly reject a permanent closure of churches. Other states that have sought a reasonable accommodation are likely to avoid these problems entirely.

Rather than attacking government officials for attempting to prevent the spread of the virus or attacking religious leaders who are trying to serve their congregations, we could look for appropriate ways to advance both needs. At a time of uncertainty, it is normal that hard questions will develop. The basic legal standards for protecting religious freedom are flexible enough to provide initial answers to most of these questions, and the process of finding appropriate accommodations can guide future resolutions to religious freedom conflicts.