I was sitting comfortably at my parents’ dining room table, which doubles as a home office these days, sipping my Aldi coffee when I read the Washington Post opinion article warning that the Wuhan coronavirus will be much worse when it hits areas of the country like this one.

The work Zoom call I was supposed to be on had gotten cut short, courtesy of backwoods internet paired with a thick cumulus cloud making its poorly timed debut overhead, so I thought I’d switch gears and take a look at the Post’s prognosis of our COVID-19 plight. Acutely aware of my own rural Midwest experience in that disconnected moment, I refreshed the article, titled, “The covid-19 crisis is going to get much worse when it hits rural areas.” It loaded. The cloud must have passed.

“It’s only a matter of time before the virus attacks small, often forgotten towns and rural counties,” the authors, Michelle A. Williams, Bizu Gelaye, and Emily M. Broad Leib, said. “And that’s where this disease will hit hardest.” The disease will hit hardest in small-town USA? A bold claim, considering the fate of urban hubs such as New York City and San Francisco. I kept reading because anything is possible, but also because I wanted to know what the authors would propose for mitigating the impending doom.

Rural America Is Senior

Among the reasons the authors offer for this upcoming heavy blow in America’s heartland is that residents of rural America tend to be older than those in urban centers, with more than 20 percent over 65 years old, which makes sense considering where the jobs were when my grandparents were part of the working class and where those jobs have now moved — into big cities, where astronomical rent prices would discourage older people, who don’t have jobs there, from taking up residence. The authors also mention poor health conditions, financial hardships, and “deaths of despair” in their bleak prediction.

They’re right. For people who contract the virus, old age and other health problems contribute to the worst outcomes.

The writers bemoan this, revealing that while urban counties have more than 50,000 intensive care beds, rural counties have only 5,600, while some counties don’t have any. “The time to prepare rural America is now,” they say.

Those numbers look dismal, sure, but have any of these writers been outside the metropolis? Common sense eludes them. Do they know what makes rural America “rural”? Fewer people. Of course New York, a city of 8.6 million people, would require more beds for its virus-stricken than Pickens County, Alabama — a rural locale the article features in its header photo — where only about 20,000 people live.

But according to the Washington Post, these rural hospitals are facing extreme difficulties. I’m sure some are. Many have lost revenue as they’ve canceled elective procedures to make way for an influx of COVID-19 patients, rationing personal protective equipment for a rush that in many cases simply hasn’t occurred.

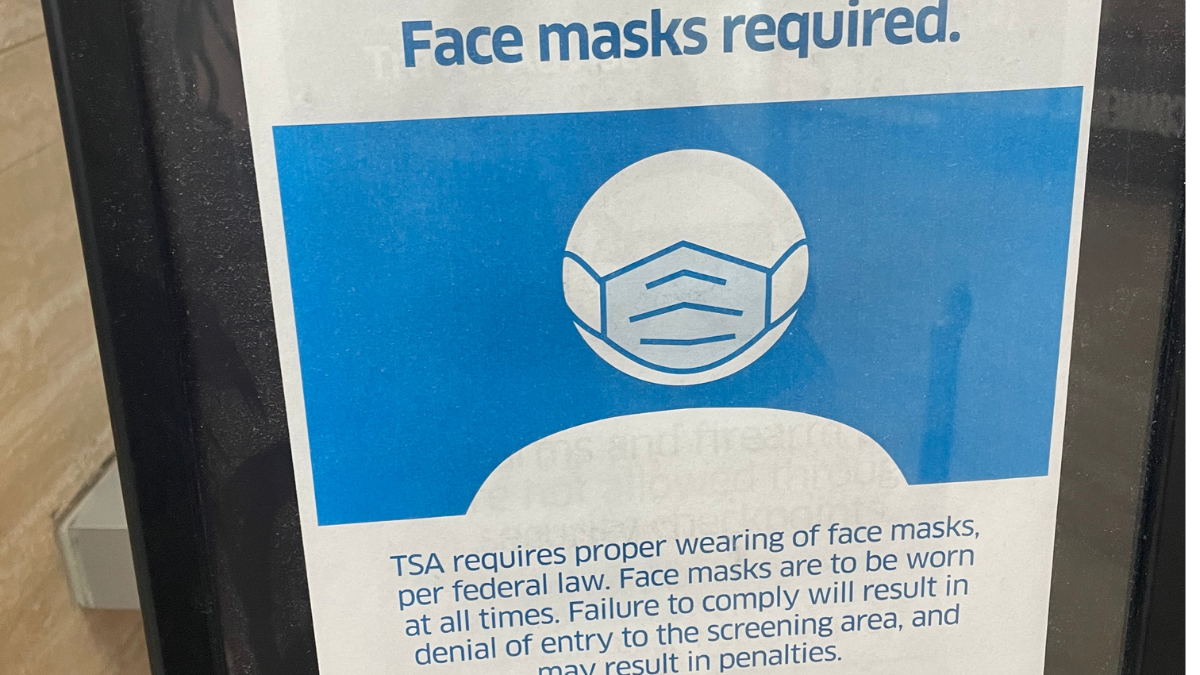

The Digital Divide Won’t Be Bridged

The solution they propose, however, to help both health systems and sick people shows that these authors profoundly misunderstand both rural America and the at-risk demographic they’re writing about. Their solution? Expand telemedicine and rural broadband. They write:

Of course, telemedicine is far from a panacea, as broadband access remains limited in so much of rural America. The stimulus included an additional $100 million for rural broadband access, but this will not be enough. In the long term, policymakers must continue to close the “digital divide,” recognizing that Internet access is both an economic and health necessity. In the short term, Internet service providers should consider rolling out mobile Internet units and providing WiFi hotspot access to temporarily increase connectivity.

I’m in rural America. My internet is horrible. I have to strike a “Lion King” pose on my back porch to get a good enough cell signal to send a picture text. With three people suddenly working from home here, we’ve run out of WiFi data three times already this cycle. I would love to have better broadband.

But broadband access won’t do anything for much of the 65-and-older population that would need the most medical assistance should this virus ravage rural communities. Only 4 in 10 adults in this demographic use smartphones. When it comes to the more vulnerable populations, digital device usage is markedly less. Only 17 percent of people ages 80 and over have a smartphone. Advancing broadband in Podunk America wouldn’t help people like my grandma, who the other day read one of my articles and referred to the comment section as people “Tweeting in.” Telemedicine would be lost on her and her TracFone.

Further, data suggests seniors with less education and lower incomes are even less likely to have smart devices and be on the grid, meaning older people in rural areas of the country, which are traditionally poorer, will be helped even less by broadband expansion than the above numbers suggest.

When then-presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren was yet persisting, you may recall her plethora of plans, one of which was an $85 billion broadband proposal for rural America. You might also remember that rural America rejected her and her lofty plans. Residents of those areas weren’t buying that philosophy then, and they aren’t buying it now.

In an ideal world, every American, young and old, would have lightning-fast internet, digital devices perfectly equipped to handle telemedicine, and enough tech savvy to tap into all the medical help they need. But rural broadband access alone won’t fix the digital divide. Bridging that tech chasm would require significantly more infrastructure and, importantly, a desire to be brought into the digital age. In my experience, many of America’s older and wiser are perfectly content to be kept in the digital dark. In many ways, I envy them.

Take my familial anecdote for what it’s worth. I certainly don’t represent rural America as a whole. But neither do the Harvard-affiliated opinion writers perched in coastal Massachusetts with their spreadsheets, high-speed internet, and array of accommodating digital devices.