Kate McKinnon tried hard to soften Hillary Clinton’s image in 2016, playing the candidate on “Saturday Night Live” as a bubbly grandmother, competent as she was warm. McKinnon tried to help out another presidential candidate in 2020, this time Elizabeth Warren. Both lost.

In both cases, McKinnon’s version of the woman departed from their dominant public image—but, of course, only to massage them. McKinnon would probably argue her excessively kind depictions are but one small way to offset rampant misogyny in the media and electorate. That’s hilarious.

In McKinnon’s hands, Warren’s professorial persona transformed from patronizing dryness into endearing quirkiness. Clinton’s off-putting arrogance became the relatable byproduct of her superior qualifications. Obvious satirical fodder—corruption in Clinton’s case, bizarre claims about Native American heritage in Warren’s—were all but absent from the impressions.

At best, Warren is popularly known as an insistent leftist class warrior with a grave personality. Clinton, as a serious but polarizing stateswoman with decades of baggage. McKinnon depicted both women as exuberant civil servants, who salivate at the sight of spreadsheets and love kissing babies.

In other words, she captured them in the most positive possible light, characters from a consultant-crafted campaign video with soft lighting, rolled up sleeves, and lots of smiles. Neither campaign could have asked for better treatment. If they wrote and directed the sketches themselves, the best they could do is what McKinnon actually did.

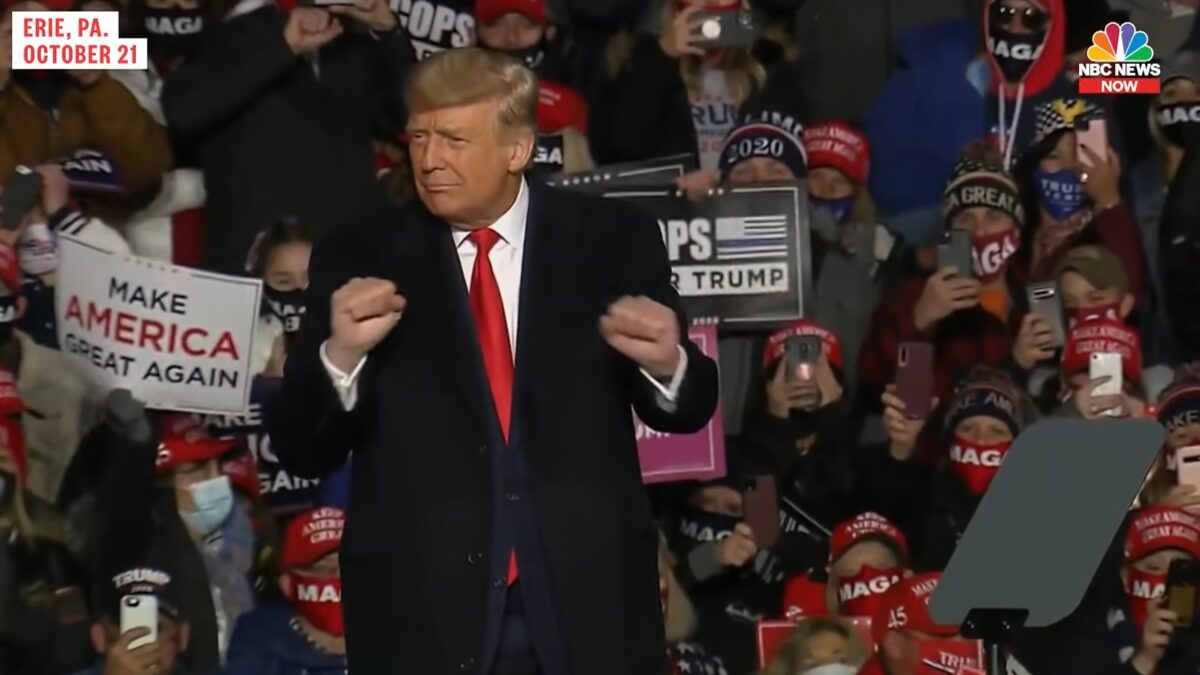

In 2016, McKinnon’s Clinton impression culminated in her bizarrely sober performance of “Hallelujah” the episode after President Trump won. Regarding “SNL’s” partisanship, we didn’t need a tell, but this would certainly have qualified. (See also the chummy backstage footage of McKinnon gushing over Clinton before her appearance in the new Hulu documentary “Hillary.”)

After Warren dropped out, she appeared with McKinnon’s version of herself in the cold open. The pair wrapped their arms around one another as they cut to break.

When Warren’s campaign faltered, Matthew Yglesias made a trenchant observation in Vox, seeking to explain to his peers “Why Elizabeth Warren is losing even as white professionals love her.”

“If you feel like Warren is very impressive and lots of people you know feel the same way, you’re not imagining it — lots of people just like you all across the country feel the same way,” he wrote. “It’s just that most Democrats aren’t all that much like you.”

McKinnon’s work captures this elite befuddlement over the rest of the country’s reluctance towards Clinton and Warren, both of whom struggled for reasons beyond rampant sexism. One of “SNL’s” few great political sketches of the Trump era captured that very befuddlement as well—but with some self-awareness. In the same episode as McKinnon’s “Hallelujah” performance, which came four days after Trump’s win, host Dave Chappelle made “Election Night” one of the show’s best moments of political satire in years, mocking the panic of coastal liberals who thought it would be impossible for Clinton to lose as they watch returns come in.

McKinnon will go down in history as one of “Saturday Night Live’s” great performers. She’s enormously talented, and one of the bright spots of “SNL’s” past decade. It’s possible she made some small measure of positive impact on the women’s public image, but there’s an important distinction between McKinnon’s portrayals and their more powerful predecessors.

Even Amy Poehler’s Clinton was slightly less friendly. Unlike Dana Carvey’s H.W., McKinnon’s impressions of Warren and Clinton were advocacy comedy, not comedy purely for the sake of laughs. That formula is rarely funny.