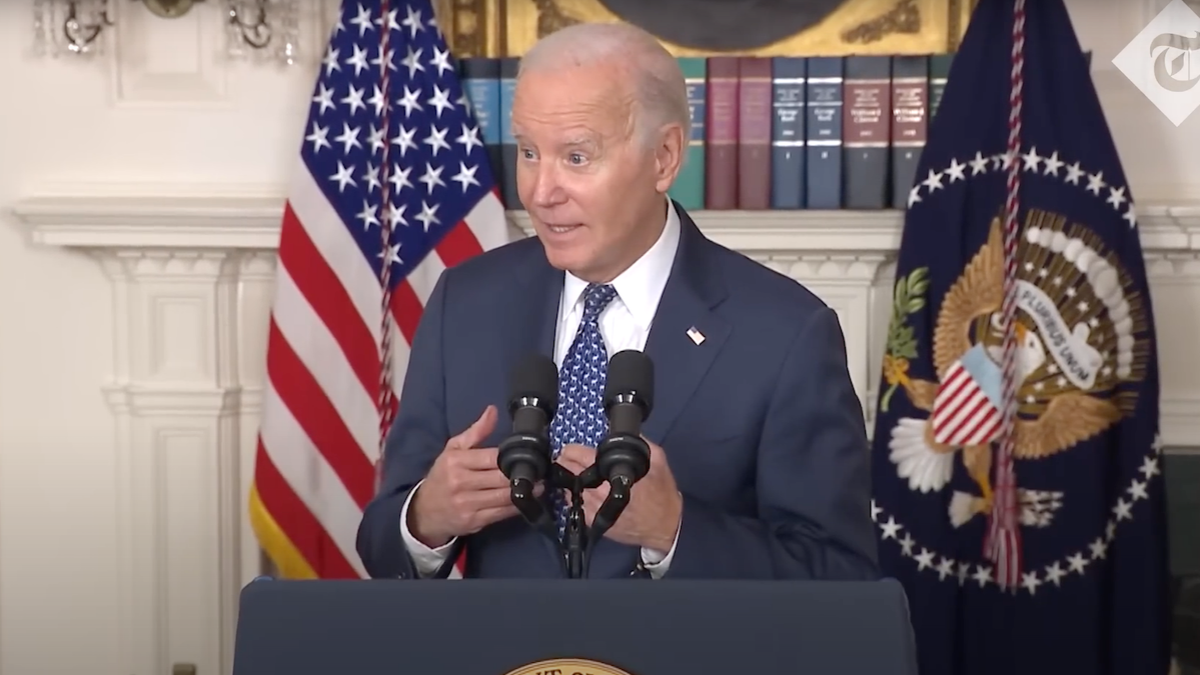

During closing arguments in the Trump impeachment trial, lead impeachment manager Rep. Adam Schiff argued it was imperative that Trump be removed from office, otherwise he’d have unchecked power and might do something like offer to sell Alaska back to Russia in exchange for support in the 2020 election.

No really, Schiff said that. He wasn’t joking. He thinks that Trump’s delay of foreign aid to Ukraine over concerns about corruption means that unless Trump is removed right now for the vague and unsubstantiated charge of “abuse of power,” then he’ll keep abusing his office and no one will be able to stop him.

Set aside the weakness and absurdity of Schiff’s half-baked argument, such that it is, and consider his claim that Trump might offer Alaska to the Russians in exchange for “support” in the next election. Schiff’s mind is apparently so addled with the debunked Russian collusion hoax that he must have thought this Alaska-Russia example would be a real zinger, really drive his point home. What he didn’t stop to consider was the historical irony in invoking the sale of Alaska.

Adam Schiff:

If Trump isn't removed he "could offer Alaska to the Russians in exchange for support in the next election or decide to move to Mar-a-Lago permanently and leave Jared Kushner to run the country, delegating to him the decision whether they go to war." pic.twitter.com/VBzkonqpmH

— Daily Caller (@DailyCaller) February 3, 2020

Why Schiff’s Historical Allusion Is Unintentionally Ironic

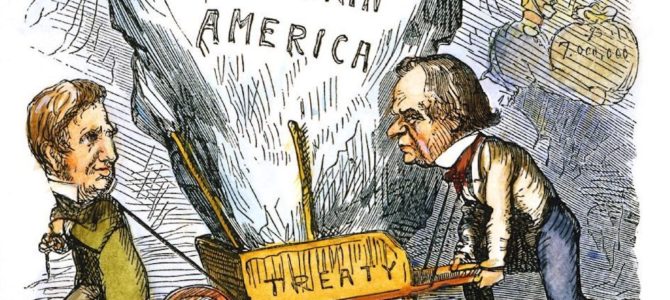

As an Alaskan who has some familiarity with my home state’s history, allow me to set the record straight: the United States bought Alaska from Russia in 1867, in the leadup to President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment. It was orchestrated by Johnson and his Secretary of State William Seward in part as a way to distract the public from domestic troubles.

In March of 1867, less than a year before Johnson was formally impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives, the Senate signed the treaty authorizing the purchase of Alaska from the Empire of Russia in a dead-of-the-night session, signing the treaty itself at 4 a.m. The entire treaty was drafted, debated, and voted on in a single night.

Things weren’t going very well for Johnson at the time. That same month, Republican supermajorities in Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act over Johnson’s veto. The law required the president to seek the Senate’s advice and consent before removing any member of his cabinet. Johnson desperately wanted to remove Abraham Lincoln’s appointee for secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton, because Stanton insisted on complying with congressionally authorized Reconstruction policies, which Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat, adamantly opposed.

In defiance of the new law, in August 1867 Johnson tried to suspend Stanton and replace him with Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, then serving as commanding general of the Army. In December, the Senate adopted a resolution of non-compliance with Stanton’s dismissal, saying it violated the Tenure of Office Act. When the Senate voted to reinstate Stanton, Grant immediately resigned as interim secretary of war. Johnson was furious at Grant, and the two had a public falling out (which led to Grant becoming the frontrunner for the 1868 Republican presidential nomination).

In February 1868, Johnson tried to appoint a replacement over the Senate’s objections, a brevet major general in the Army named Lorenzo Thomas. When Thomas personally delivered the news to Stanton, Stanton barricaded himself in his office, ordered the arrest of Thomas for violating the Tenure of Office Act, and notified Congress of the situation.

Outraged at the president’s actions, House Republicans quickly drafted and overwhelmingly approved a resolution to impeach the president, which passed 126 to 45, with 17 members abstaining. Four Democrats joined Republicans in approving the resolution. A week later, the House approved 11 articles of impeachment.

The Purchase of Alaska Was Corrupt to Begin With

As for the purchase of Alaska, the Senate signed the treaty in March 1867 but the House didn’t appropriate funds until July 1868, after weeks of debate over the treaty and fiery denunciations of the Senate treaty from all quarters.

Then, suddenly, the mood in the House changed. The funds, $7.2 million (about $108 million today), were appropriated in a vote of 113 to 43, with 44 not voting. Suspicions of bribery abounded, and a committee was even convened to investigate. But the investigation came to nothing when the Russian minister to the United States, Eduard de Stoeckl, refused to allow himself to be questioned—and refused to explain why more than $125,000 had suddenly gone missing from his bank account.

So Alaska finally came into possession of the United States, about two months after President Johnson escaped removal from office by a single vote in his Senate impeachment trial. He would serve out the remainder of his term in ignominy and impotence.

The moral of the story is this: If you’re Adam Schiff and you want to show how corrupt it might be to offer to sell Alaska to the Russians, you might want to consider that the purchase of Alaska in the first place was by all accounts thoroughly corrupt.