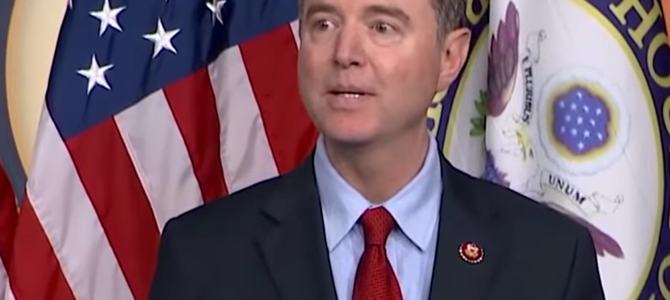

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi finally named the managers who would present the articles of impeachment to the Senate and subsequently prosecute the impeachment case. The lead manager is House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff. Given the strong possibility Schiff will be called as a witness, however, should he even be permitted to serve as a manager in the upcoming impeachment trial?

According to Module Rule of Professional Conduct 3.7(a):

A lawyer shall not act as advocate at a trial in which the lawyer is likely to be a necessary witness unless:

(1) the testimony relates to an uncontested issue;

(2) the testimony relates to the nature and value of legal services rendered in the case; or

(3) disqualification of the lawyer would work substantial hardship on the client.

Generally speaking, a manager’s role in an impeachment trial is similar to that of a prosecutor’s in a criminal trial. Like a criminal trial, the president’s lawyers will serve as defense counsel, and the Senate will serve as the jury.

In cases of presidential impeachments, the chief justice of the Supreme Court presides over the trial. Moreover, all managers typically come from the same party, as they are all in favor of impeachment. While the managers serve as prosecutors, they do not determine the rules of the trial, which the Senate decides.

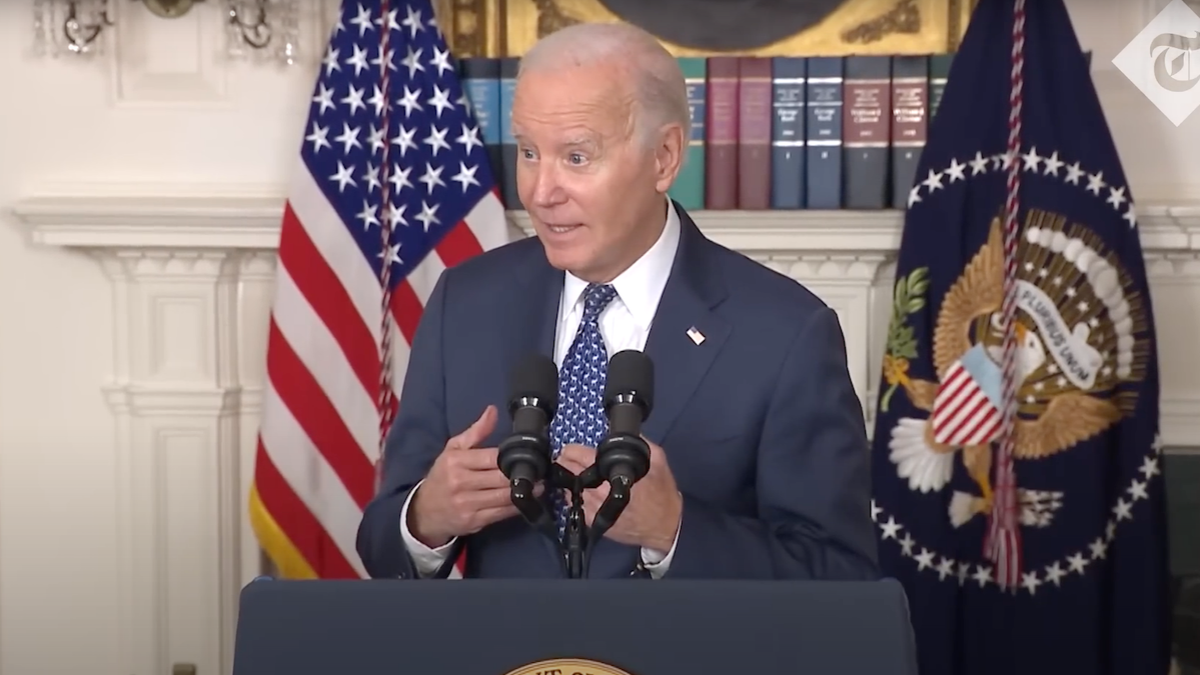

Schiff Doesn’t Fit Impeachment Manager Criteria

According to Democratic strategist Michael Gordon, an ideal manager choice would be a “credible, least-partisan-seeming” member, rather than an “overly partisan” member who would “not really be open to the facts.” Joe Lockhart, a spokesman for President Bill Clinton during his impeachment, noted that when choosing managers, congressional politics might win out over the most qualified managers.

According to Lockhart, “You could go, for example, with committee chairs and you could go by seniority. And that doesn’t necessarily give you the most effective prosecution.” In the instance of President Donald Trump’s impeachment, Schiff and the other managers will prosecute the case.

Rule 3.7 specifically applies to trials. While impeachment is quasi-judicial in nature, it is presumed that Rule 3.7 would still apply to those lawyers serving as impeachment trial managers. Moreover, the comments to Rule 3.7 provide some clarification as to the purpose of this rule. Specifically, Section (2) of the comments states:

The tribunal has proper objection when the trier of fact may be confused or misled by a lawyer serving as both advocate and witness. The opposing party has proper objection where the combination of roles may prejudice that party’s rights in the litigation. A witness is required to testify on the basis of personal knowledge, while an advocate is expected to explain and comment on evidence given by others.

During the interminable impeachment inquiry, House Republicans intended to call Schiff as a fact witness, but House Democrats prohibited them from doing so in accordance with the one-sided resolution that gave Schiff the ultimate say as to who would be permitted to testify as a witness.

Senate Republicans Will Likely Call Schiff as a Witness

By way of review, the original whistleblower in the Ukraine matter filed a complaint without any firsthand knowledge of what transpired, failed to check off the appropriate box indicating he had met with one or more members of Schiff’s staff, and subsequently concealed these interactions despite reports that Schiff or members of his staff contacted or met with the alleged whistleblower before the complaint was filed.

Moreover, Schiff allegedly knew about the complaint or its contents before it became public. He also sent out a tweet on Aug. 28, 2019, before the complaint was public, that very closely resembled the allegations in the complaint. Schiff has also maintained he does not know the name or identity of the whistleblower and previously claimed, “We have not spoken directly to the whistleblower.”

At one point during the public testimony phase of the impeachment inquiry, however, Schiff threatened House Republicans of possible ethical violations if they named or mentioned the whistleblower. How could Schiff possibly know if this person’s name were mentioned if Schiff didn’t know his identity?

Given these various inconsistencies, Schiff will likely be called as a witness, as his testimony is relevant. The question, then, is whether he is a necessary witness. To date, House Democrats have prevented the whistleblower from testifying.

Therefore, Schiff could be deemed a necessary witness, for example, if he is the only person who could identify the staff members who initially spoke with the whistleblower, what they talked about, his relationship with the whistleblower including when and how they met, when they first discussed the Ukraine matter, what they discussed, whether anyone else was privy to their conversation, whether he encouraged the whistleblower to file a complaint, whether he played any role in preparing the complaint, and why he initially denied speaking with the whistleblower before he had filed his complaint. Schiff’s testimony will also shed light on his credibility and potential bias.

Schiff’s potential dual role as lawyer and witness does not appear to fit into one of Rule 3.7’s exceptions. Specifically, his testimony does not relate to an uncontested issue or to the nature and value of legal services. To the contrary, his testimony directly relates, in part, to the initiation of the whistleblower complaint and the underlying motivation and circumstances surrounding the filing. Finally, given that Schiff’s “team” consists of six additional and qualified attorneys, his disqualification as manager would not result in any hardship.

Schiff’s Dual Role Creates a Conflict of Interest

In this case, Schiff’s ability to serve as lawyer and witness could hinder or prejudice the president’s case in the eyes of the Senate and the American public. His dual role could also create a potential conflict of interest, depending on the information elicited through his testimony.

Rep. John Ratcliffe, R-Texas, was concerned about Schiff’s potential conflict of interest during the inquiry phase. According to Ratcliffe, Schiff has a conflict of interest in light of his secret interactions with the whistleblower before his false complaint against Trump was even submitted:

It’s more than just bias — it’s an actual legal conflict of interest. Schiff is using his authority as a chairman presiding over an impeachment inquiry to prevent the investigation and discovery of facts about his own actions or the actions of his staff.

He is essentially a witness in the trial over which he is presiding. He has a conflict of interest because his testimony is relevant to the origins of the impeachment process that he is simultaneously conducting, directing, and managing.

If the Senate decides to allow witnesses during the trial, which is another contentious issue, the president’s defense team should be permitted to call Schiff as a witness and to question him about the circumstances behind the whistleblower complaint, his apparent inconsistent statements, his alleged conflict of interest, and his obvious bias.

While Schiff cannot avoid questioning by virtue of the fact that he is a prosecutor in the impeachment trial, his role as manager deserves a second look because of these various considerations. Finally, given his unwillingness to name the whistleblower and his staff members who initially spoke with the whistleblower, his testimony appears necessary, especially if nobody else can provide the needed information.

If this means he cannot serve as a manager, he should immediately step aside and allow the other managers to continue without him.