One of the joys of learning is in realizing how interconnected human endeavor often is. Sometimes these connections are well-known and easy to reference, but at other times they’ve fallen into relative obscurity.

Such is the case with the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s comprehensive new exhibition, “Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet,” where visitors can discover the work of an artist who isn’t very well-known in this country, and in so doing discover important connections between his work and that of other, more familiar, figures from art history.

Swiss-French artist Félix Vallotton (1865-1925) was a member of “Les Nabis” (“The Prophets”), a group of young artists from the Académie Julian in Paris, whose better-known members included Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) and Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940). They worshiped groundbreaking Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), executed art in a wide variety of styles and mediums, and generally enjoyed doing what young adults often do: poking the middle-class establishment of their day right in the eye. Not surprisingly, like many of the former hippies who slopped about in the mud at Woodstock, some of these art rebels later ended up as members of that bourgeois establishment.

From Traditional to Anti-Traditional

Like his schoolmates, Vallotton began by following a rather traditional route, in classes taught by Academic painters such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905). Countless hours were spent in drawing classes and studying the collections of the Louvre, with the goal of producing paintings that looked as realistic as possible. Vallotton’s 1885 self-portrait, for example, shows us a fresh-faced, properly dressed young man with cropped hair and the questioning look of a serious schoolboy.

This was not to last. Fast-forward to his 1897 self-portrait, and Vallotton has become a hipster. His once short, light-colored hair is now long and dark, he sports a Van Dyke beard, and wears a tatty old fisherman’s sweater over a collarless shirt. He still has that serious, somewhat quizzical expression, but now the eyes are puffy and underlined by dark half-circles.

This is probably because he and the other “prophets” have been spending too much time getting plastered in the cafes of Montmartre with roaring drunks like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901). The artist’s effect on Vallotton is obvious in works such as “Street Scene in Paris” (1895). Yet Vallotton took a step further the very flattened, graphic style for which Toulouse-Lautrec became famous in his posters and playbills, in an artistic medium that had been practically abandoned in late 19th century Europe: the woodcut.

Influenced by Japanese woodblock prints, Vallotton began combining the flat, graphically heavy lines of the Ukiyo-e style with his own strong, often satirical images of Parisian street life. In “The Demonstration” (1893) for example, a large group runs away from the unseen police, and are rushing so quickly that they’ve knocked off the top hat of a bearded, elderly gentleman at the lower left.

In another set of woodcuts from 1895, Vallotton explored the often intimate relationships between musicians and their instruments. I particularly enjoyed seeing “The Violin” and “The Flute” from this series, the former reminiscent of Sherlock Holmes relaxing in front of the fire at 221B Baker Street, the latter with an almost painfully chic white cat who appears in several other Vallotton prints.

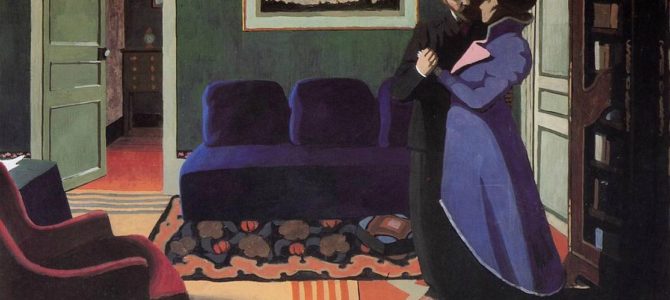

In several series, Vallotton examined the attractions and perils of adult relationships, as viewed through the often hypocritical social conventions of his time. Secret romances and a voyeuristic fascination with other people’s stolen moments are captured in his 1898 “Intimacies” series, such as in “The Cogent Reason” and “Extreme Measure.” In these images, which were wildly popular, one can see the antecedents of work by artists such as Edward Gorey (1925-2000), whose off-kilter illustrations often evoked tortured relationships between elegantly dressed, secret lovers, set against the blackest of black backgrounds.

Growing Interest in Vallotton’s Work

Despite his almost single-handed revival of woodcut prints, by the turn of the century Vallotton chose to abandon them for a time. For one thing, Les Nabis fell apart after their final joint exhibition in 1900, although many of the artists remained close friends. The year before, Vallotton had married the daughter of one of the wealthiest art dealers in Europe, and moved into a grand apartment, complete with fine furniture, plush carpets, and hot and cold running servants. At the same time, Vallotton’s paintings began to attract more interest, not only in Paris, but also in Vienna, where the Secessionists took strongly to his work.

It’s easy to see why paintings like “Moonlight” (1894) would have appealed to the same Austrian artists who had fallen in love with the work of Vallotton’s Scottish contemporary, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1929). Vallotton’s moon, clouds, and their reflections in the water all shimmer with touches of metallic paint, a technique Mackintosh also used, and anticipating by more than a decade the luxurious “Golden Phase” of contemporary Gustav Klimt (1862-1918).

Works like Vallotton’s “The Visit” and “The Ball,” both from 1899, have that particular planar quality from his woodcuts that the Secessionists also loved to employ in their art, where the eye is tricked into seeing a three-dimensional object seemingly flattened into two-dimensions, while forgetting that the object was always two-dimensional.

It’s at this point that Vallotton’s work as a painter starts to become particularly interesting. His “Model Sitting on a Divan in the Studio” (1904), for example, has a wonderful plushness about it, as the bare foot of the young woman pushes itself into a fold in the kilim rug at her feet. Vallotton’s 1905 portrait of his wife, Gabrielle, shows us a woman we might not describe as pretty, nor in the first flush of youth (she was a widow with three children when they married), but is nevertheless an appealing figure with a kind, thoughtful expression. Figural paintings such as these allowed Vallotton to build upon the more monumental forms that he had begun exploring earlier in his woodcuts.

The Elephant in the Exhibition Space

At this point it appears necessary to acknowledge the presence of an elephant in the room, or more specifically in the exhibition space. Vallotton’s 1907 portrait of Gertrude Stein is on display in the show, alongside the much more famous portrait of her by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) painted the year before, thereby inviting the viewer to compare and contrast the two. While it’s an interesting juxtaposition, the subject of these portraits brings to mind the old adage that, if you’ve nothing nice to say, say nothing at all, so let’s move along.

My favorite work in the exhibition carries the awkward title, “Box Seats at the Theatre, The Gentleman and The Lady” (1909). Our vantage point is from the stalls, from where we can see a lady in a large, fashionable hat, crowned with a swirl of tulle, who is resting her gloved hand over the edge of the balcony above us.

We can’t see her or the man with her distinctly, and indeed the lower half of the man’s face is hidden from our view. Whatever the nature of their relationship, they’ve spotted us staring at them, and Vallotton has captured that sense of shame in which we know that we’ve been caught staring.

Compositionally, not only does the picture strongly recall such differing reference points as the work of Édouard Manet (1832-1883), and even “Drowning Dog” (c. 1819-1823) from the “Black Paintings” by Francisco de Goya (1756-1828), but just as Vallotton anticipated and influenced Klimt, it’s clear in this picture that he also anticipated and influenced Edward Hopper (1882-1967). It’s no wonder then that social commentary, such as here or in “The Provincial” (1909), kept Vallotton busy during this period, and led to some of his strongest works. At the same time, he must have wondered how, from where he began, he ended up becoming yet another member of the bourgeoisie.

Maybe the Bourgeoisie Is Where We All Belong Anyway

A late-period piece in the show neatly brings us back to where we began with Vallotton’s output. The subjects in “Red Peppers” (1915) are shown on what appears to be a small, marble-top table. They’re accompanied by a butter knife, which wouldn’t be much good in cutting through the thick skin of these fruits. Note however that the blade rather ominously reflects part of the pepper next to it, making it seem as though it’s stained with blood. It’s a beautifully executed work, reminiscent of the artist’s earlier, schoolboy realism, but it’s also a somewhat disturbing picture.

Perhaps the image reflects, in still-life form, Vallotton’s perceptions of the horrors of World War I. The subject caused him to finally return to woodcuts for the first time in more than a decade, creating a series of prints titled “This Is War.”

In addition, like his contemporary Henri Farré (1871-1934), whom Federalist readers may remember reading about last year, Vallotton volunteered to fight for France, but was considered too old. So, he was brought to the front lines by the French government to sketch battle scenes he later turned into finished paintings. (Note to any museum curators who may be reading this: it would certainly behoove you to put together a show dedicated to the wartime canvases executed by both of these artists.)

Although he lived on for a few more years after the war, still producing pieces for an artistic world that had largely passed him by, in 1926 Félix Vallotton died of cancer at the age of 60, with Gabrielle by his side. Given his enormous output of more than 1,700 paintings alone, and the connections he forged through his artistic and personal circles, he was never forgotten in places like France or his native Switzerland.

However on this side of the pond, he had the misfortune of seeing his career fall between those of Cézanne and Picasso, without ever achieving the international renown or success of either in this country. With this timely reexamination of his work, The Met has managed to bring back into the public gaze an artist who was perennially fascinated with showing the art-going public what it often did not want to look at: itself.

“Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet” is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 26.