The perfect companion accompanied my family’s trip West this summer in the modern covered wagon: A new, single-volume book of U.S. history. As our RV motored across the plains, I read of how they were discovered and settled. I looked across the prairies, the badlands, and the mountains and imagined myself coming in an ox-drawn cart instead of a motor vehicle with a gas stove and bathroom.

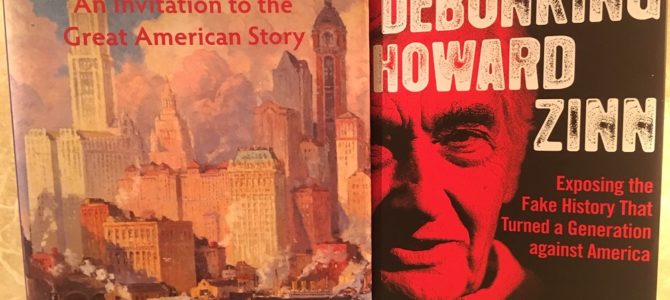

“Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story,” by University of Oklahoma historian Wilfred McClay, is extremely readable. It’s written in a conversational but not casual tone, and thus approachable to readers from around age ten onward (if the ten-year-old is accustomed to reading large books like “The Lord of the Rings,” as mine is). An attractive writing style may be its first virtue, because an open door is required for people to enter.

A second virtue is the book’s brevity. To be sure, it is a large and somewhat heavy volume, of 429 pages not including the end material. But that is not too much gas for racing across approximately 500 years of history. I found myself constantly wishing to hear more about the people and ideas in the book, and sad but understanding to instead be whisked away to the next set. Thankfully, McClay provides an extensive “additional reading” list to help satisfy a problem inherent to writing a one-volume overview of American history.

Considering a new book of American history requires, however, more than structural basics like these. Context is extremely pertinent. “Land of Hope” is published in a year in which hatred of America seems bigger than ever.

To take a recent and prominent example, The New York Times, once the United States’ paper of record, has newly released the “1619 Project,” named after the year in which African slaves first arrived on American shores. The project purports to be a work of history: “aim[ing] to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.”

But it is better described as anti-history propaganda. To take just one demonstration of this, its premise and name fully ignores that Native Americans frequently enslaved each other on this continent long before Europeans arrived. It also sidelines the fact that most of the African slaves brought to the Americas were sold by enemy African tribes, who also routinely held their fellow man in slavery going back centuries. Native Americans held black slaves. African Americans held black slaves. The whole world has held slaves.

In other words, if America was founded on slavery, so was just about every civilization. Should they all be razed right now? Just how does one propose to do that, exactly, without creating mass murder and mayhem? Since America is not unique in its regrettable past allowance of chattel slavery, it does not deserve to be singled out as an object of hatred, largely for the left’s political advancement. We can and need to have a conversation about how to judge one’s country for its sins and recover from them, but that requires starting from factual instead of ideological grounds.

Yet surveys have shown for decades that most Americans today know nearly nothing about their history, and when it is taught in public schools and universities it is usually either influenced by or saturated with leftist politics. Most Americans thus have no intellectual defenses against such lies. Knowledge is the starting point for wise reflection and substantive conversation. It is the antidote to propaganda.

This is likely the reason McClay’s history is billeted in marketing materials as “the long-awaited antidote to Howard Zinn anti-Americanism.” “[E]xisting accounts simply fail to tell our country’s story with energy and conviction,” the press release says. “They also disproportionately reflect the outlook of radical critics of American society, whose one-sided accounts lack the balance of a larger perspective and have had an enormously negative effect upon the teaching in high schools and colleges.”

This is all true. But this might make readers expect to read something more polemical, a sort of mirror image of Zinn’s bestselling anti-American propaganda textbooks used in countless U.S. public schools. McClay’s book is not one bit polemical. If anything, it is genial, open-minded, and when critical it is critical out of love for its subject matter, rather than hatred.

It is not a work of advocacy, but of history. McClay presents accusations against America in their context but without covering up genuine wrongs such as slavery. “Land of Hope” comes across more as a balanced and honest account than a specific response to a work that spreads Communist messaging.

As such, it is a good starting point on what should be all American patriots’ quest to revive respect for our country’s achievements and ideals through a better knowledge of their effects and development in history. But its approach is not in itself sufficient to achieve that purpose. More is needed.

To make an analogy, Americans’ affections for and knowledge of their country need to be fed. “Land of Hope” does so. What it does not provide, however, is an antidote to poisoned food. It may strengthen minds enough to toughen them against diseases, but already diseased minds, and minds susceptible to disease, need something stronger than nourishment. They need medicine, an antidote to the poison.

Next on my reading list for books of that character is Victor Davis Hanson’s “Carnage and Culture.” Also recommended as antidote reading, as Joshua Lawson notes in his excellent list here, is Thomas G. West’s “Vindicating the Founders” and “The Political Theory of the American Founding.” Another new book deserves a place on this stack to help minds switch from defense to offense for America’s ideals, history, and traditions: “Debunking Howard Zinn,” by Mary Grabar.

Grabar, whose essays on education I’ve edited for many years now at several publications, does a meticulous takedown of Zinn’s lavishly selling, Hollywood-vaunted work of so-called history, “A People’s History of the United States.” Zinn’s book was first published in 1980 and is now estimated to have sold some 2.6 million copies. College Board’s rewrite of its Advanced Placement U.S. history course features Zinn’s book and embeds his anti-American philosophy.

The tragedy of all this, of course, is that Zinn’s book is concentrated poison. Using a careful review of his source materials and claims, as evidenced by her nearly 1,000 footnotes, Grabar documents quite clearly and conclusively that Zinn is not only a plagiarist but a liar. His presentation of key events and figures of American history, such as Christopher Columbus, slavery, the NAACP, World War II, and the civil rights movement, also straight-up regurgitates Communist propaganda.

Here’s just one example, from page 222 and 223 in Grabar’s book. She shows how Zinn selectively quoted from American documents to make it look like the United States was interested getting Vietnam’s natural resources, not in defending it from a communism our nation understood to be evil and dangerous. The very same documents Zinn quotes actually prove the opposite of the points he makes with them when one reads the material he left out.

“One wonders if Zinn had simply not read the volumes that he presumably edited [of the Pentagon Papers],” Grabar writes. “Either that or he deliberately left out key information.” As she shows, he used this falsifying tactic so many times in “A People’s History” it becomes hard to believe it’s an accident.

Thus not only is Zinn’s book a pack of slipshod lies that even leftist historians will not stand behind, it is a pack of slipshod lies that appear to be told purposefully to set Americans at each others’ throats. And it has been quite effective. Many Americans believe the false and self-immolating narrative that their nation is fundamentally and unreformably racist, sexist, and genocidal.

For all its faults, the United States and the Western civilization that created it have been the best protector of people’s rights and freedoms the world has ever known. We definitely have done many evils. We continue to allow great evils today. But worse societies fill the earth, and historically have been far more common. People who don’t know this gravely endanger what is and has been for hundreds of millions of people the last, best hope of a broken earth.

One of the other sobering reflections upon reading Grabar’s work is this: Why has it taken nearly 40 years to get a systematic, scholarly debunking of Zinn’s evil, destructive lies? How is it that two generations of history teachers and professors lacked the knowledge and love of America to keep this poison book out of the hands of millions of American school children? How was “Land of Hope” not written and used in classrooms 40 years ago instead of this Molotov cocktail barrage aimed at the greatest country in world history? How is it that as governor of Indiana Mitch Daniels was unable to get this book yanked from public school classrooms, and that no other Republican politicians have tried?

Not only did they not stop it, and force taxpayers to pay for their own children’s and the next generation of voters’ mental destruction, legions of these people in positions of authority enthusiastically welcomed a book they should have instantly realized is full of politically motivated falsehoods that are destructive of the country that pays their salaries and made possible just about every good thing in their lives. Can leaders who so terribly fail American children, taxpayers, and the nation deserve any credibility or respect?