If you’re looking for a heartwarming family film, you’re in luck this week. “Dumbo,” Tim Burton’s triumphant return to Disney, fits the bill. The story of a family coming together to save an adorable flying elephant, rediscovering their love for each other in the process, is the most beautiful Disney movie in a long time, which is exactly what Burton was hired to make.

Disney rarely spends money on talent and almost never allows talent to impose their vision on a story. The company wants to protect its various Disney brands and take no risks. “Dumbo,” then, is an exceptional event, and a bit difficult to explain, until you remember how stunned people were about the look of Burton’s “Alice in Wonderland,” which went on to gross $1 billion worldwide. It’s very hard to create anything fascinating with blockbuster-budget movies, because there are so many controls imposed by people who have money but no idea what audiences love, and it’s impossible if you have to make something family friendly, too, unlike, say “The Dark Knight.”

Burton is the amazing exception to this rule. His movies are instantly recognizable because of his style, which puts vulnerability and danger into beauty, remaining true to what we know about the tragic side of life. Burton’s had big hits for about 30 years now, because he knows what the American audience wants. This makes him irreplaceable.

A movie looks beautiful if the cinematographer is good, but it still needs a visionary director. Ben Davis, for instance, shot both “Dumbo” and “Captain Marvel,” and the latter looks embarrassingly cheap in comparison, like pre-ordered CGI. He also shot the much-better looking “Guardians of The Galaxy” directed by James Gunn, who’s back in the saddle for the third “Guardians,” after losing his job for tweeting awful jokes years back. Disney knows it sometimes needs directors who can wow audiences.

Burton is also an unusually honest storyteller, especially in the age of sarcasm, so he’s the best example of what the magic of the movies means. Directors like him use technology, enormous budgets, and the great expectations of the era of blockbuster entertainment to tell simple stories. It’s true we need a lot of showmanship to pay attention to stories we’d otherwise ignore, so we can feel they’re plausible, but ultimately that’s what we want—people like ourselves in situations whose moral importance we recognize.

“Dumbo” is about a father, played by Colin Farrell, trying to provide for his two children in a bad situation. They recently lost their mother and he’s somewhat clueless without his wife. Worse still, he’s a World War I veteran, returning without an arm. He’s trying to be a man, a provider, and protector, but he has few opportunities.

Worst of all, he’s in the fast-dying circus business. Before the war, he did cowboy stunts as the headlining act for Max Medici—played by Danny DeVito, who’s been acting the circus freak in Burton movies since playing the Penguin in 1992’s “Batman Returns.”

Here, Burton indulges our sentimentality and really plays on the wonder of nostalgic shows. The whole circus business is going to hell and we feel for all the freaks down on their luck. The first wonderful montage is this entire, movable show packing up and turning into a train, only to set up shop again somewhere else down the line. It’s not celebrity or the limelight that attracts us to them. It’s the freedom of moving about the vast expanse of America in search of business, discovering places and people. But steam trains are a thing of the past—the modernity of the previous century, now empty of the exciting promise of the future.

We want Max Medici and his circus freaks to succeed, however improbably, so Max buys an elephant, to give his circus some exotic appeal, and soon finds himself owner of a calf whose enormous ears make him look ugly. Enter Dumbo, who discovers by accident a penchant for flight. Fascination with a feather makes Dumbo sneeze his way to take off. Every time this happens it makes for delightful scenes, but they also set the stage for Dumbo’s career as a freak—a thing of wonder, but also a creature of mockery, beloved, but also harassed. Just like a modern celebrity.

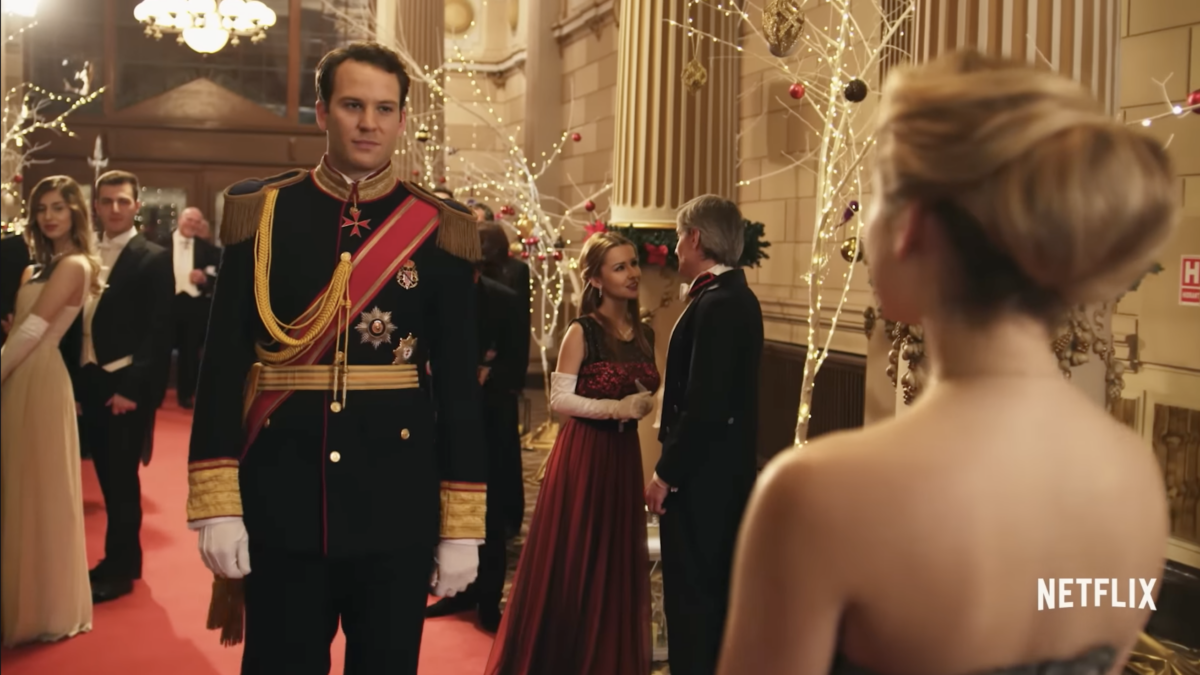

Now, the story becomes impressive. Like the children’s movie, “Dumbo” also has something to offer adults. Burton identifies the circus with celebrity and our modern entertainment industries. His villain is the owner of Dreamland, the future of amusement park entertainment—in short, Walt Disney!

He’s played by the great Michael Keaton, a fixture of Burton movies going back to “Beetlejuice” in 1988. He combines technology and a ruthless head for business, and buys Dumbo to leverage him for the financial backing he needs to take over America’s imagination. He embodies the behind-the-scenes corruption and tyranny that’s always been tolerated in entertainment and it’s Dumbo’s job to destroy his empire.

But why should Burton want to exorcise the ghost of Walt Disney? Disney made Americans believe in the magic of the movies, achieved through animation, which means making images come alive through the use of light and electricity. Motion and an infinite imagination seemed to fit a young nation, newly empowered, always restlessly on the move, always looking for new things by which to define itself.

For about a century—the American century!—we’ve lived through this experience, mostly convinced it’s of our own making and therefore the future. But eventually the dream turns into nightmare, the fascination with celebrity becomes dark, and we learn that fantasies don’t come true. Burton has the villain say: Everything is possible—just imagine!

This is an attack on the Hollywood that lives off our fantasies, which is now dying with the celebrities it created. The fantasy-makers know it, too: Look at our next great magician after Walt Disney, Steven Spielberg. Up to “Jurassic Park,” he made Americans believe in magic all over again. Whether it’s aliens, like in “E.T.,” or technology, a fantasy of the future captivates us, promising we can get there if we dare to dream.

But Spielberg turned against this imagination. His only amazing movie since “Jurassic Park” was “The Adventures of Tin-Tin,” which had new 3D technology, but was all about an old European cartoon that rehearsed the fantasies of the age of colonial empires, an experience utterly foreign to America. His American fantasies, however, have lost their innocence, getting ever darker and more fearful of technological tyranny over life: “A.I.,” “Minority Report,” and “Ready Player One,” a trilogy of despair over the American future.

Burton knows all this. After all, he’s the magician who took over from Spielberg. Burton also charmed America with his imagination, but he never claimed to create new national fantasies. He doesn’t want to keep feeding our hopes to the exploitative corruption of Dreamland, but to burn it down and liberate the freaks imprisoned there. “Dumbo” symbolically effects this revolution that’s supposed to set America free from corporate-entertainment control. He wants finally to break the spell. We’ll take our chances afterward.

Burton is the freak who stands up for freaks. As individualists, they’re all-American. They stand out. It’s why they attract attention. They’re like the rest of us in some ways, even if freaks and their audiences cannot always get along. But now we all have something new in common. We’re living through the end of the circus Walt Disney helped start. From now on, we must look to ourselves for freedom, not to larger-than-life fantasies. This is a message for which conservatives, and all Americans, should be grateful.