After more than two years of waiting, one of the world’s most popular podcasts has returned with its third season. “Serial” dropped its first two new episodes on Thursday morning.

First exploding onto the platform as a viral hit in 2014, “Serial,” an offshoot of “This American Life” and hosted by NPR veteran Sarah Koenig, introduced us to Adnan Syed, and the concept of telling true crime stories via podcast. Koenig’s thoroughness in investigation and willingness to be wrong created a 12-episode story that became the most popular podcast in the world. Whether or not the listener believed Adnan’s claim to innocence, or thought the jury got it right, “Serial” presented an undeniably addictive format for intricate storytelling.

Two years after the final installment of the whirlwind second season of “Serial” featuring Bowe Bergdahl, Koenig is back with not one new story, but many. Each episode of season three takes place in the Cleveland Justice Center Complex, where Koenig and her producer, Emmanuel Dzotsi, spent more than a year taking in the justice process, interviewing the prosecutors, judges, defenders, and the accused.

Cleveland was chosen simply for Koenig and team’s unfettered access to every corner of the complex. Unlike the first season, which followed Syed through a high-profile murder trial, season three focuses on generally smaller criminal matters in Ohio’s second-largest urban center. Each episode will focus on one individual, rather than a long story spread out over the whole season.

While the premise may superficially seem less exciting than the preceding two seasons, the third season offers an incredibly new perspective on the world of criminal court, and the justice system as a whole.

Koenig masterfully presents the information as she perceives it. She doesn’t have an axe to grind, she just wants to know what happens to a person in Cleveland after the cuffs go on. She follows her subjects from incarceration, to courtroom appearances, to jail time, to probation, and to what happens when the justice system cuts them loose.

In the first episode, the subject, “Anna,” has been arrested for a bar fight. She’s a young, white woman who was at a shady bar with some shady friends when some men began harassing her. She admitted to being drunk, out of place, and possibly overly aggressive. One thing led to another, and she ended up punching a police officer.

Anna’s saga is followed for about a year, and while her final outcome seemed to be a light punishment on paper, the repercussions were far greater. She lost her job, spent an evening in a police car, was jailed for four days, and had a court tab that put her into collections. Sure, she made a mistake. A big one. But the supposedly “light” punishment put her so far into the hole that it will take years of struggle and luck to be able to live life above-board.

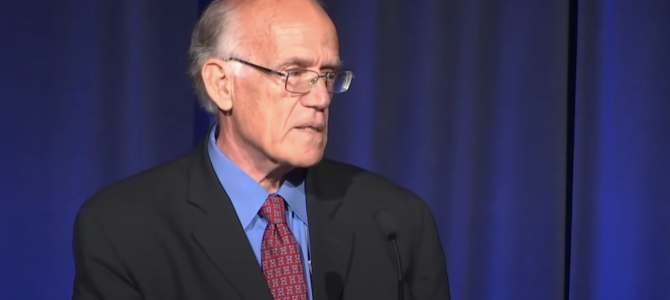

The second episode focuses primarily on Judge Daniel Gaul, a Democrat who has a reputation in the Justice Center Complex for coloring way outside the lines of constitutional law, and practicing racial prejudice with reckless abandon. The first soundbite we hear of Gaul in his courtroom is during one of his famous lectures.

He addresses a defendant as a cartoonish old schoolmaster would an unruly student: “You’re pathetic, dude. You’ve got a mortal character flaw.” He further berates another defendant, “Tyrell,” asking him where his dad is, and if his siblings are half or full, hazarding a guess that he grew up in a fatherless family. He often addresses African-American defendants as “dude” or “brother” and refers to “baby mommas” and “baby daddies” when discussing family life of the accused.

In the episode, we hear Gaul threaten more than one client with jail time if he finds out they are having a child out of wedlock, making it a term of their probation. At one point he says, “You’re on probation to me and you have more kids out of wedlock that you can’t afford to pay for, I’m gonna send you right back to the institution.”

Dzotsi seems genuinely shocked by the blatant un-constitutionalism of this threat, only to learn that it is par for the course for Gaul. The judge sees his habitual use of empty threats and demeaning slang as way to, as the judge puts it, “connect” with defendants. “I want to speak to them in their idiom. In language they can understand… ‘Hey, dude, get real.’”

Because of legislation in recent years aimed at lowering prison populations, Ohio courts have had much greater ability to grant probation over jail time in lower felony charges. This is a delight to Gaul. He views putting defendants on probation as a way to keep tabs on them for years to come, to be involved in their lives, claiming to want to make them better but truly controlling them. He boasts, “I put more people on probation than anyone else in this courthouse.”

“Vivienne” pleaded to felony drug possession in 2015. Gaul gave her probation. At her fifth violation, Vivienne’s attorney asked for her to be transferred to drug court, a courtroom specifically created for non-violent addicts. In drug court, the emphasis isn’t on punishment as much exploring the best way to help people get better. It’s proven to work for many addicts, at least better than traditional criminal court.

Gaul seemed almost offended by the request to have her moved from his watchful eye. The request was flatly denied, and never revisited.

After some time, Vivienne had violated her probation several more times, and is portrayed as begging Gaul to send her to inpatient care. “I have a sickness,” she says. The judge, after calling her “pathetic,” retorts, “You call it a sickness and I call it a crime.”

That begs the question: if there were a better option for her, why wouldn’t he let her take it? How could a judge enjoy seeing a woman continually violate her probation with no sign of improvement? It remains to be seen whether his portrayal on “Serial” will affect his upcoming election, but the Cleveland Plain Dealer has endorsed his opponent, Republican Wanda C. Jones, after previously endorsing Gaul.

Each episode promises a deep dive into a case or system that will undoubtedly compel the listener. The inner workings of the court are nothing like what is dramatized for television, and even unlike what people likely know from highly publicized trials.

Gaul estimates he has seen 40,000 cases in his 27 years on the bench. The figure is astounding, and gives us an idea of how many of our fellow Americans have been through criminal court in their lives. Like any system, this one is flawed.

It can also be great. It can save lives, and it can condemn them—both through inflamed sentences and through the trauma of being put through a year-long court battle. Fairness and justice is often at the hands of a single person, and he doesn’t always get it right.

“Serial” has tapped into an underreported and fascinating mine of story material, which I am already enthralled by. Season three promises to give a voice to the voiceless, to humanize those so often underserved by the public, and to tell some fascinating stories. New episodes are released Thursdays on any podcast platform.