The Week recently published a column conveying Damon Linker’s disgust over the most recent wave of sex scandals, titled “The Unbearable Ugliness of the Catholic Church.” Linker says he is repulsed by the institution as a whole and is leaving the church. It’s an understandable reaction, but based on poor reasoning.

The self-described Catholic convert concludes in his piece:

The world can be a dangerous place. … But to wade through the toxic sludge of the grand jury report; to follow the story of Theodore McCarrick’s loathsome character and career; to confront the allegations piled up in Viganò’s memo — it is to come face to face with monstrous, grotesque ugliness. It is to see the Catholic Church as a repulsive institution — or at least one permeated by repulsive human beings who reward one another for repulsive acts, all the while deigning to lecture the world about its sin.

No thanks. I’m done.

And I bet I’ll have a lot of company headed for the door.

I cannot argue with the sentiment here. I, too, have felt like bailing from the Barque of Peter these past months. Like Matthew Walther, another Catholic columnist at The Week, I certainly feel contempt and revulsion for much of the church hierarchy right now.

But as someone who has chosen to be a part of the church (for faith always requires a free act of will for Catholics), I am morally obligated to argue against these feelings. In other words, I empathize with Linker, but think he is making the wrong decision. That’s because hypocrisy, even that which stinks to the highest heaven, does not and cannot disprove truth.

Do As I Say

There’s a methodological problem at the heart of many of the responses to the scandal. It goes something like this:

- The Catholic church teaches that priests and bishops must refrain from sexual relations.

- Many not only engage in sexual relations, a shocking number have engaged in sexual assault and systematically covered it up.

- Therefore the church is hypocritical.

- Therefore the church is wrong.

- I should not be part of a wrong organization.

- Therefore, I’m heading for the door.

Note that the first two premises here are incontrovertibly true, and the first conclusion (if, by “church” we mean a significant number of its leaders) is absolutely sound: The Catholic church is deeply hypocritical in the sense of “full of hypocrites.”

But is the church wrong? That question can be split into numerous pieces. First and foremost: Is the church’s teaching on clerical celibacy wrong? That is an important question that escapes the bounds of a Federalist article, but I’ll note this: If we are saying that celibacy is wrong because it causes males to engage in the most revolting forms of sexual assault, then we are really saying something shocking about men. It boils down to the claim that men who do not have sex, including by choice, are essentially ticking time bombs of violent perversion.

To the men reading this article: Do you think this about yourself? For those of you who are married: Do you believe, for example, that if some unfortunate accident were to prevent your wife from having conjugal relations with you, your thoughts would turn to how to seduce and abuse minors and how to create a web of secrecy and lies to cover it all up? Whether they intend to or not, that is precisely what everyone who makes the “celibacy equals sexual assault” argument is affirming: If you are not having sex, fellow brethren, you are a moral monster in the making.

This is a bad argument that has no empirical evidence to support it. However, there’s a deeper problem that goes beyond the question of celibacy itself. That is the problem of using hypocrisy as the standard for determining moral truth. Does deviating from a principle in conduct that one otherwise affirms necessarily disprove the truth of the principle itself?

Survey Says: Nothing

The answer is no, and the reason is similar to the reason we do not derive objective truth from taking surveys: Just as there is an independent relationship between what people believe to be true and what is, in fact, true, there is also an independent relationship between how people should behave and how they actually do behave.

Consider, for example, infidelity. According to a recent study, 16 percent of all Americans engage in some form of adultery (although for older men, the number is as high as 26 percent). Presumably, the people who provided the answers for this survey believed that what they were engaging in was “cheating” of some sort. Otherwise, they would have answered “no” to the question of whether they were unfaithful to their spouses. In other words, they recognize the moral legitimacy of the principle of faithfulness itself, but chose to act otherwise. That makes them hypocrites.

But does that, therefore, mean we have good reason to question whether adultery is, in fact, wrong? Let’s say, for example, that it will never be the case that 100 percent of spouses will be faithful—that it’s an impossible standard to live up to. Fine, but so what? Just because some people deviate from a principle they say they believe does not mean that principle is wrong. In the case of infidelity, we do not ask whether we should be faithful by observing others’ behavior. We ask whether it is good to be faithful.

The answer is true even regardless of whether people live up to the moral standard. Consider the golden rule, for example. Hypocrites, all of us, right? Yet following the logic of the presence of hypocrisy meaning the absence of moral legitimacy, we would have to conclude that the golden rule is wrong. What should determine whether something is good by asking whether it is true, and true in such a way that it remains true whether anyone — or no one — behaves accordingly.

Who Do You Say That I Am?

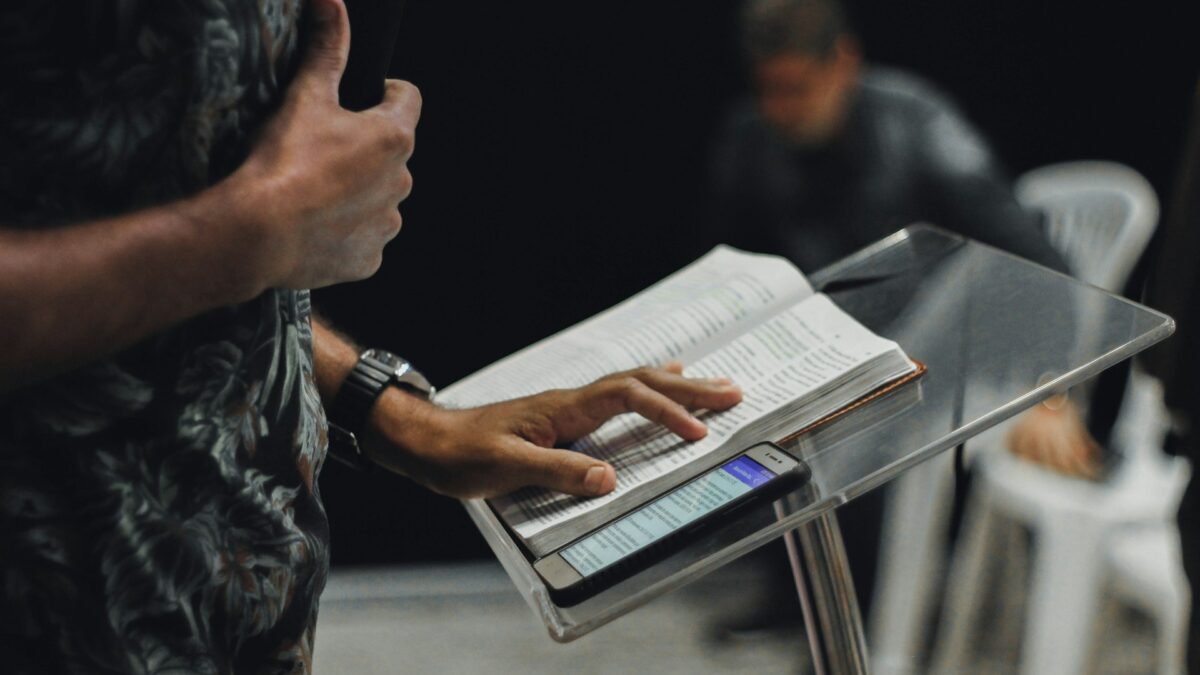

So to bring this back to the scandal in the Catholic church, let me say this: For all of those, like Linker, who are considering heading for the door, please pause, turn around, and look up. That man you see hanging there is what this is ultimately all about. Not celibacy, not scandal, not hypocrisy. Since this is a distinctively Catholic problem right now, let me end with some distinctively Catholic questions, those first liturgically asked (and answered) at baptism:

Do you reject Satan? And all his works? And all his empty promises? Do you believe in God, the Father Almighty, creator of heaven and earth? Do you believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was born of the Virgin Mary was crucified, died, and was buried, rose from the dead, and is now seated at the right hand of the Father?

For the love of God, please do not let the sins of the fathers determine your responses to these questions. The crucifixion of that man hanging in the building you’re thinking of leaving confirms your belief that everyone is bad and many are wicked, especially as they try to claim otherwise in unctuous self-righteousness.

But before you give up, let me suggest reading one last bit of the Bible, and then decide whether to close the door for good: “After this many of his disciples turned back and no longer walked with him. So Jesus said to the twelve, ‘Do you want to go away as well?’ Simon Peter answered him, ‘Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life, and we have believed, and have come to know, that you are the Holy One of God.'”