Engraved on a plaque in Cooperstown, New York—the home of baseball’s Hall of Fame—is a quote from Jaques Barzun’s book, “God’s Country and Mine”: “Whoever wants to learn the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball.” This is probably more indicative of a bygone era, but baseball still holds an important place as America’s pastime.

On July 29, a new class of inductees will be enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, who are universally recognized as two of the most talented ballplayers who have ever lived, will continue to be a story not for their induction but for their absence.

So far the voters have chosen to punish Bonds, Clemens, and other suspected steroid users by keeping them out of the hall even though their statistics dictate otherwise. The debate will continue among baseball writers and fans.

However, Bonds and Clemens are not absent in Cooperstown. Their achievements are chronicled in the nearby baseball museum. Although their legacy is tainted, those who are tasked with preserving the history of the game and teaching it to baseball fans each year understand that these stories and records are still part of that history and cannot be ignored. The balance they’ve struck can inform us about other hotly contested issues in American life, specifically how we view America’s founders, who have historically been regarded as heroes but are increasingly vilified.

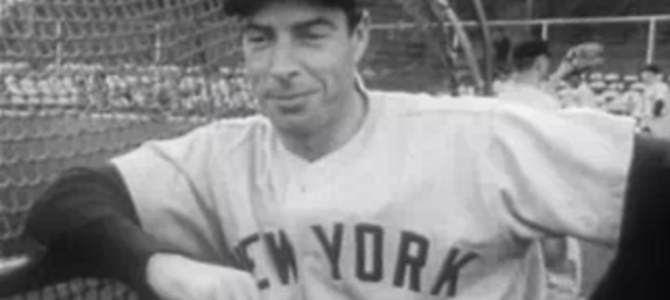

‘Where Have You Gone, Joe DiMaggio?’

Part of Cooperstown’s lore is its shrine-like qualities dedicated to those who served as our heroes when we were kids. Until recently, sports were traditionally an escape from the pressures of the real world, where we could cheer for people not tainted by the bitter fights playing out in the rest of our society. This is why, in the tumultuous 1960s, Simon and Garfunkel sang, “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.”

Growing up in the 1990s, my summers were filled with professional ballplayers hitting prodigious home runs. Mark McGwire broke one of baseball’s most historic and cherished records the night before I started high school in 1998. The nation had turned its eyes from the M&M Boys—Mantle and Maris—to Sammy Sosa and McGwire.

Upon DiMaggio’s death in 1999, Paul Simon recounted in a New York Times op-ed a chance meeting with the Yankee Clipper that occurred shortly after the song asking where he’d gone hit the airwaves. DiMaggio asked Simon why he asked that, when DiMaggio was still very much a part of pop culture. Simon responded: “I said that I didn’t mean the lines literally, that I thought of him as an American hero and that genuine heroes were in short supply.”

Simon continued:

Now, in the shadow of his passing, I find myself wondering about that explanation. Yes, he was a cultural icon, a hero if you will, but not of my generation. He belonged to my father’s youth: he was a World War II guy whose career began in the days of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig and ended with the arrival of the youthful Mickey Mantle (who was, in truth, my favorite ballplayer).

In the 50’s and 60’s, it was fashionable to refer to baseball as a metaphor for America, and DiMaggio represented the values of that America: excellence and fulfillment of duty (he often played in pain), combined with a grace that implied a purity of spirit, an off-the-field dignity and a jealously guarded private life. . . .

He was the antithesis of the iconoclastic, mind-expanding, authority-defying 60’s, which is why I think he suspected a hidden meaning in my lyrics. The fact that the lines were sincere and that they’ve been embraced over the years as a yearning for heroes and heroism speaks to the subconscious desires of the culture. We need heroes, and we search for candidates to be anointed.

Two years after Simon wrote that, Bonds put his name in the record books with 73 homeruns. Two years after that I sat in Yankee Stadium as Roger Clemens won his 300th game and recorded his 4,000th strikeout in the same night. Before long, the baseball world was grappling with the effect of steroid use and how it would taint the record books of America’s pastime.

Baseball, the Metaphor for America

As Simon wrote, it’s been fashionable to refer to baseball as a metaphor for America, and with good reason. For example, players from Latin America, Japan, and other parts of the world give up their way of life for the chance to reap the benefits of playing Major League Baseball. America is the land of immigrants seeking opportunity, and our national pastime continues to tangibly reflect that reality.

But with the good comes the bad. Baseball was segregated. Our Hall of Fame honors people who took part in that segregation. Many men would be in the Hall of Fame if they hadn’t been relegated to the Negro Leagues because of the color of their skin. Those who care about the history of baseball, like those who care about American history, grapple with this grim reality.

Writing about the need to find heroes to anoint, Simon continued:

Why do we do this even as we know the attribution of heroic characteristics is almost always a distortion? Deconstructed and scrutinized, the hero turns out to be as petty and ego-driven as you and I. We know, but still we anoint. We deify, though we know the deification often kills, as in the cases of Elvis Presley, Princess Diana and John Lennon. Even when the recipient’s life is spared, the fame and idolatry poison and injure. There is no doubt in my mind that DiMaggio suffered for being DiMaggio.

The recognition that heroic characteristics are often a distortion, or at least an incomplete picture, has been growing in America’s political life. Heroes who have been universally venerated throughout American history have been increasingly attacked.

A plaque recognizing George Washington’s membership at a church in Alexandria, Virginia was removed because he had owned slaves. Students at the University of Virginia painted graffiti on a statue of the university’s founder, Thomas Jefferson, because he owned slaves. There’s no doubt that these types of things will continue to occur in the years ahead.

So we must ask ourselves, are the monuments recognizing political heroes meant to honor like the plaques in the Hall of Fame, or inform more like the exhibits in the nearby museum? If we’re honest, the answer is both.

Neither a Footnote Nor the Whole Story

To a much larger degree than our sports heroes, our historical political heroes—the men and women who labored to build a nation and craft a Constitution aimed at securing life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—are subject to the forces of intense political tribalism. Depending on one’s perspective, the sins of our national forefathers often become everything or nothing. They are never just part of the story. It’s an all or nothing proposition.

In many ways this is understandable. Governing properly is much more important than honoring people who can throw or hit a ball better than the rest of us. Grappling with steroid use pales in comparison to dealing with the effects of slavery and segregation as we move forward as a nation.

Many Americans see our Founders’ sins as little more than a footnote in the story of the founding of our nation. In recent years, many others have tried to make those sins everything in an attempt to set aside the profound, world-altering ideas—the self-evident truth that all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights—in an effort that would replace that foundational truth. A balance must be struck between these two positions as we examine our history as a nation.

Praise the Good, Mourn the Evil

As the curators of baseball history have done in Cooperstown with baseball milestones and records, we must not pretend that history didn’t happen because we don’t like the story. It would be to our great disadvantage to attempt to forget or rewrite the story. As George Santayana famously wrote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” If true, it likely follows that those who refuse to learn from it are also doomed to repeat it.

It is imperative that we figure out a way to keep America’s Founders in perspective so we can learn from both the horrific injustices they were involved in and the incredible, world-bettering ideas they unleashed. As Simon wrote, deification often kills, and we must not let the deification of our Founders make it impossible to continue to build on the foundation of their terrific successes.

At the same time, our nation is growing increasingly lonely in search of heroes that can lead us into the future. Bonds and Clemens are perfect examples of heroes tainted because of their sins but remembered because of their successes. Let’s not forget the heroes we’ve always had and the hard lessons they’ve taught us simply because they were humans with a difficult story full of tragedy and triumph.