You’ve probably been suffocated with emails even more than usual recently as tech companies announce privacy updates to comply with a new European Union law. This is simply artful gluteus maximus covering. Whatever improvements vendors have made to their privacy policies still represents half a loaf, because these modifications do not completely embrace what should be at the core of any privacy regime: informed consent.

Informed consent has been an ethical precept mostly confined to medicine. It says adults have the right to know all the implications, ramifications, and risks in a medical procedure before assenting to it.

This fundamental principle should also sit at the center of the relationships between the users of digital services and the providers of them, who, in the course of their delivery, typically collect, harvest, manipulate, and sell all personally identifiable information they can. Users of digital services should have the right to know how these use their personal data before consenting to its use, and in an easy to understand and easily accessible way. If the informed customer or visitor chooses not to allow the harvesting, the vendor then could disallow access or terminate the user’s participation in the service.

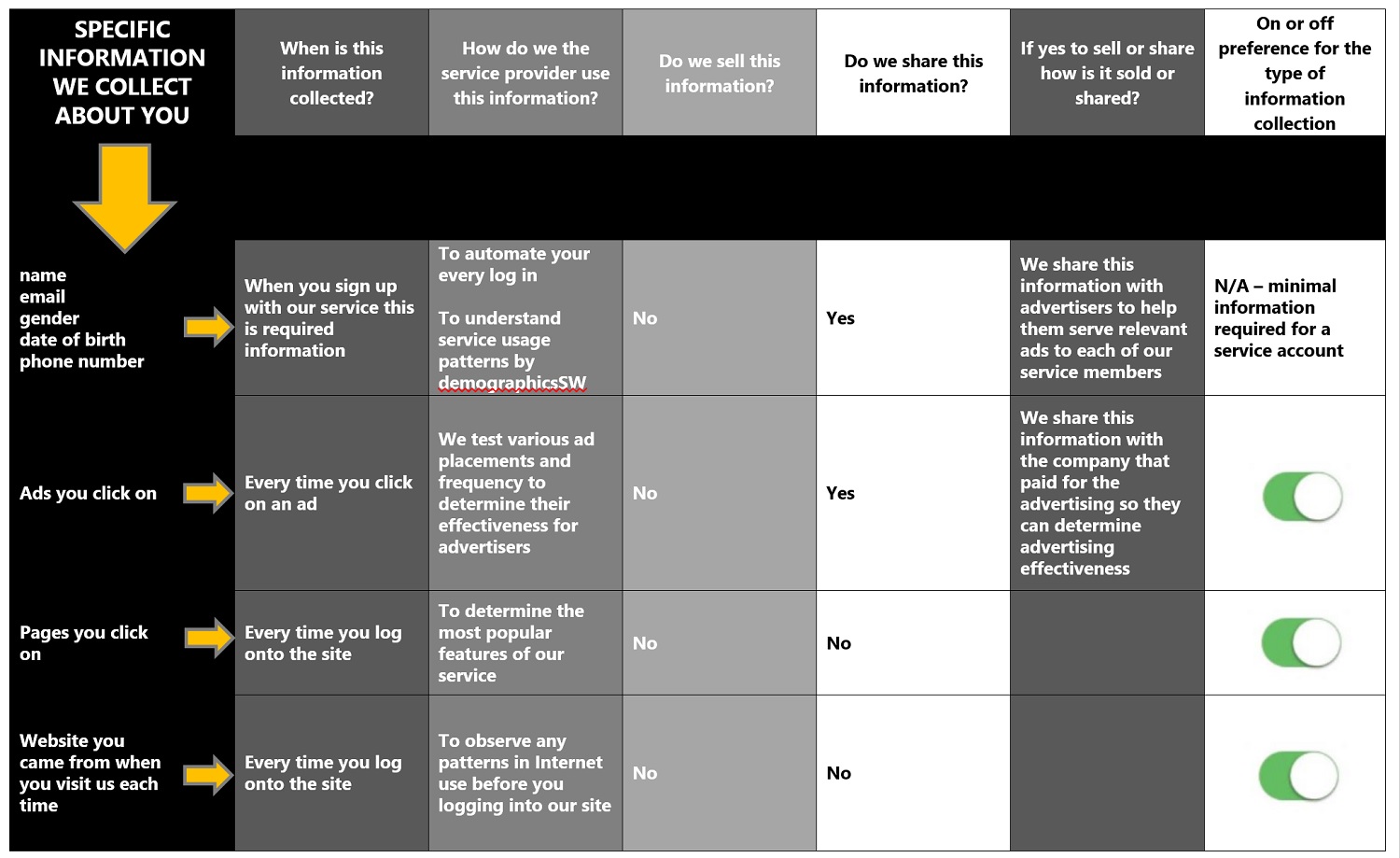

What would an informed consent framework applied to a privacy regime look like? It could start with a “privacy grid” like the one below.

The Privacy Grid: Like the Schumer Box, Only Better

The best example of a privacy grid in action can be found at LinkedIn. Under your account settings appears a list of categories like “Logins and Security” and “Site Preferences.” Contained under each of these categories are specific action items that can be turned on or off individually from a radio button appearing on the right.

Privacy settings are not enabled with radio buttons, but the overall interface gives you a feel for the privacy grid concept: a one-stop shop for itemized statements of data handling policies by provider and radio buttons after each policy that give users complete control over each.

In spirit, a privacy grid embraces the idea behind the “Schumer Box,” the table that by law must appear on every credit card promotion. Named after New York Sen. Chuck Schumer and enacted in the late 1980s, the intent of the legislation was to:

- Provide credit card users an-easy-to-understand summary of critical card information, including interest rates and other credit card fees.

- Ensure a consistent form of presentation across all credit card issuers, making apples-to-apples offer comparisons easier.

- And provide consistent location from where credit card users can reference this key information.

What would elements to a privacy regime built around informed consent look like? Here are a few key elements:

- A privacy link on front page, with mandatory minimum point size for the font.

- Summary of the privacy grid.

- The grid itself, with the proposed features consistent across all businesses in the U.S. that capture value from personal data.

- Every website would use the same URL to display its privacy policy, such as www.microsoft.com/privacypolicy; www.spotify.com/privacypolicy, or whatever URL scheme is agreed upon.

The service provider consistently presenting each instance of private data usage would be the cornerstone of an informed consent privacy regime. How can you make informed decisions if the relevant information is stored in different places with various providers, is stored in more than one place within a provider, the information uses different terms to mean the same thing across providers, is presented in more than one format, and offers no easily available location where the customer can exert some control over the information being used?

Presenting information in simple English for easy digestion and comprehension, as well as the ability to choose privacy preferences line by line for each instance of data use, is foundational to informed consent. Today service providers obfuscate about privacy, and often deliberately so. Critics consider this “forced consent.” The default is acceptance of any and all uses of information by the service provider at the time of signup.

Informed Consent Is a Market-Oriented Approach

An informed consent approach to regulating privacy in the United States is fundamentally conservative and libertarian, and puts people in control instead of a federal bureaucracy overseeing blunt-force legislation. Informed consent also embraces a market-based approach to privacy.

If your information is the product in exchange for free services, why not enact a framework that would allow a market-oriented barter: in exchange for just basic information, you get basic service at the website. If you decide to share more information, you get more service. Put another way, allow more user opt-out options line by line in a privacy grid, receive less value from the service provider, as opposed to the all-or-nothing commercial vacuum-cleaner approach.

Consider this use case that highlights the market-driven mechanics of a privacy regime. A user might decide to turn off a service provider’s capability to track the user’s every move while visiting the service. When the user attempts to turn off an instance of personal data collection by clicking on a radio button in the far-right column, a popup would appear, telling the user that disabling this data collection activity means deactivating the service.

The service provider would be saying: disable this, and we automatically close your account. The subtext message is crucial: we are providing this useful service for free. If you are uncomfortable with this type of data collection, then we cannot do business with you.

Service providers are loathe to couch data collection policies explicitly in the language of a market exchange—we don’t charge you money for our stuff in exchange for your personal data—figuring people would leave en masse. But when a market research company undertook a study recently to determine whether users would pay for an ad-free version of Facebook, 40 percent of respondents said they would be willing to pay $1 to $5 a month.

That’s about half what Facebook already earns from each user in ad revenue. An advertising business model means collecting lots and lots of data for advertisers to spend money at the site. Even if the advertiser doesn’t know who the ads are targeted to, the service provider certainly does. Apparently for Facebook, a plurality of users are not willing to pay $10 a month in exchange for more privacy, at least in this survey.

So, when the push of a mouse comes to shove, people will grumble but they’ll likely continue to use sites they are addicted to. Service providers will have to gamble that, in the name of informed consent, in the end people will consent because of the level of value they get from the service. Isn’t this a core principle of a market exchange?

Denying site access from a refusal to allow cookies, or refusing to sign up for free to establish an account from which session cookies become meaningful, is exactly the kind of transaction a true informed consent privacy regime would encourage. You want to see some great photography at Pinterest? Want to listen to the Beatles’ high-quality audio stream at Spotify? Want to use a basic, no-cost application from hundreds of vendors in everything from contact management to project management to collaboration? Come right this way, but first tell us a little bit about yourself.

What Big Challenges There Are to This Approach

Some challenges to this approach loom, such as how to handle third-party service sign ups using login and profile information from another service. Facebook is frequently a go-to site for other service providers to encourage new signups. Where does one service end and another begin?

Also, this essay did not explicitly address app downloads and device data collection. Yet the precepts of informed consent can start here. Ever try to change the data collection settings on a Tablet running the Google Android operating system? It’s ridiculous: Layers and sub-layers of obscure choices with associated radio buttons. You’re scared that if you change a setting you’ll blow up the functionality you’ve grown accustomed to. This is likely Google’s desire: Don’t touch that dial!

An informed consent approach to privacy sets the stage for far greater user control but at the expense of perhaps some service value. In an informed consent privacy regime, people would be forced to think hard about how much personal information they are willing to part with in exchange for services whose oxygen is data collection. That’s because, no matter what Uncle Bernie says on the hustings, there is no free lunch.