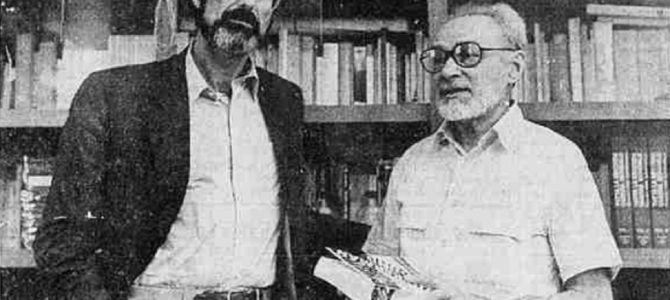

Philip Roth has left us. I’m grieving so terribly that I can barely write these words. He was the greatest American novelist of the postwar world, and of the prewar world, and all the wars in between.

When I met with him a few short months ago to collect my share of royalties for “The Phalluses Of Prague,” an anthology of Eastern European male writers we’d translated together, he displayed his usual intellectual rigor, wit, and honesty, about which you’ll just have to take my word. Novelists speak a secret language, after all, that the uninitiated cannot understand. Together, Roth and I plotted to steal Kazuo Ishiguro’s Nobel Prize, but decided against the plan.

“It’s only a matter of time before I get my own,” he said.

Tough luck, bubbeleh, and now we’re all heartbroken. Roth has slipped away, vanished, transformed into that great breast in the sky. As both my student and my teacher, Roth taught me (and learned from me) the value of literature, and the importance of writing sentences even when you don’t like the president.

I so admired his books, especially “The Priapic Toothache,” in which Nathan Zuckerman pretended to be David Kepesh and Peter Tarnopol while having imaginary sex with his dental hygienist in Israel, all under the watchful eye of a novelist who may or may not have been Philip Roth or Alexander Portnoy. His concerns were our concerns, and therefore universal.

Of all the Great White Male Novelists who wrote novels about being great and white and male in the late twentieth century, Roth was the greatest and whitest and malest. He outlived them all—Bellow, Mailer, Vidal, Updike—although he didn’t outlive me, which is good.

As he once wrote in his novel “Indigestion,” which was also a memoir, “Don’t be afraid of the dark, or of death, which is quite a feeling. Fear will wash you out to sea, but don’t worry, because you are still here. We must go on. Someday, you will ache like I ache.” Truer words have never been written.

With the deaths of Roth and Tom Wolfe, the ultimate Plot Against America has been enacted. Our great land, where intellectual giants once lunched on the company dime, has devolved into something quite stupid. Every time a writer dies, a devil gets his horns. We must continue to write in his name, or at least tweet it out. We must resist. We must persist. Our hearts will go on.

In many ways, I’m enthralled by the level of my grief at Roth’s death, which I will continue to advertise heavily in hopes it will get me a little attention. Sure, he reduced his female characters to receptacles for jizz, but he did so with sentences so elegant, they tasted as good as finger sandwiches at a Viennese café.

No one understood Jewish life in America better. He wrote about Jews as Jews wanted to be written about or not written about, that is for certain. Roth left no sacred cow unassimilated, no sandwich unordered, no photograph of Franz Kafka unsigned. “This is actually me,” he’d write, “except I have bigger eyebrows.” And who could doubt him?

Farewell, O great observer of literature and the national scene. After all, you once said, in a literary acceptance speech, “America is a disease or a carnival or maybe a pogrom. I don’t know, please just give me my award already, it’s cold in this room.”

We all wanted to be Philip Roth. No one came close. Except for me. Roth once said, after we’d polished off a case of wine at his Connecticut estate, “I am a good writer, but I can’t even begin to compare to you, Pollack. My knowledge of the Jewish experience in America may be vast and deep, but compared with your insight, I am but a flea in a circus featuring an outrageously masturbating puppeteer. To you I bow, my good sir.”

For that, more than anything else, I’ll miss Roth terribly. Farewell, my good friend. I will carry on, and surpass, your legacy. Only Joyce Carol and a half-dozen Jonathans stand between me and the ultimate honor. I’m certain that I’ll triumph, and I’ll do it without complaint.