The Newark Museum’s new exhibition, “The Rockies and the Alps: Bierstadt, Calame, and the Romance of the Mountains,” provides an enlightening examination of two simultaneous currents in nineteenth-century American and European art. As they began to leave the studio to seek inspiration directly from nature, American artists became enthralled with the monumental expanses of their ever-expanding Western frontier, while European artists reexamined long-familiar Alpine terrain with new eyes.

Exploring themes of philosophy, travel, science, and technology, this show not only demonstrates how Western attitudes toward mountainous landscapes changed during the nineteenth century, it also provides a great opportunity to consider how educators, including homeschoolers, can and should take advantage of such shows and institutions in their communities.

To begin, a confession: until I traveled to see this exhibition, I was unaware of the Newark Museum’s vast and deeply interesting holdings. There are ancient Egyptian mummies and Native American weavings; Victorian glass, tile, and silver decorative objects; superb American paintings by Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keefe, and the Peales, among others; even a planetarium and a science collection.

Newark is so close to New York City that you can see the Manhattan skyline quite clearly from the Amtrak platform. It makes me wonder why, in the many decades I’ve gone back and forth between DC and New York, I’d never previously thought to step off the train and have a look about.

So, Let’s Get Off that Train and Into the Museum

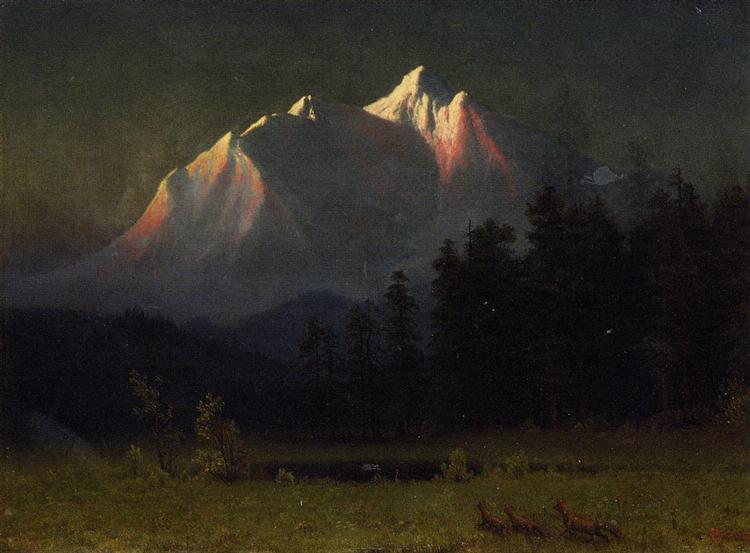

“The Rockies and The Alps” draws on both the Newark Museum’s own holdings, which contain one of the largest collections of American landscape painting in the world, as well as pieces lent from both public and private collections. The exhibition opens with an arresting, well-designed juxtaposition of two mountain landscapes with quotes from the American painter Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and the Swiss painter Alexander Calame (1810-1864).

The pairing sets the tone for the show. Not only were Bierstadt and Calame colleagues, but these two works—“Western Landscape” (1869) by the former and “Mountain Torrent Before a Storm (The Aare River, Haslitel)” (1850) by the latter—are of roughly the same size and era. Throughout the show, the American and European paintings, drawings, photographs, and other objects mirror or complement each other, so visitors can see how each side of the Atlantic looked at the untamed landscape and man’s relationship to it during the same time period.

“We need to break down the provincialism,” commented Newark Museum’s Associate Curator of American Art William Coleman during my tour of the exhibition, “of thinking of American art as developing independently of other art.” Like their European counterparts, American artists were reading and thinking about philosophical ideas that first developed during the Age of Reason, such as Edmund Burke’s writing on the concept of the “sublime” in nature, or Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s fantasy of man’s recapturing lost perfection in nature by abandoning the decadence of urban life. Romantic poets such as Lord Byron and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and essayists like Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, expanded these notions.

Leisure travel through the Alps became increasingly popular in the nineteenth century, and many well-known American and European artists felt called further afield into exploring these rugged landscapes in search of inspiration. On the same wall of the exhibition where we see two Alpine drawings by the American artist Thomas Cole (1801-1848), founder of the Hudson River School of painting, and the Alpine sketchbook of Samuel F.B. Morse (1791-1872), best known to us today for the invention of the Morse Code but a highly gifted American artist as well, we also see watercolors of the Alps by two of their best-known British counterparts: painter and philosopher John Ruskin (1819-1900) and the towering J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851).

Exploring the Terrain of Victorian America and England

At the same time, artists working in the young American republic began to explore the wilder places within their own territory. In the mid-1820s, Cole and others began exploring and depicting the Catskill Mountains northwest of New York City, where the rugged natural surroundings fit perfectly with the Romantic literature of the day.

By the eve of the Civil War, William Smith Jewett was showing Americans the natural wonders of California’s Sierra Nevada in his “Yosemite Falls” (1859). Other artists such as John William Casilear and Sanford Robinson Gifford created images of Colorado and Wyoming which, when seen together in the show, effectively contrast the very different types of landscapes of American mountain ranges, from deep lakes to bone-dry deserts.

Growing rail networks brought more artists and visitors to these rugged mountain locations than ever before, and the development of photography allowed visitors to record a precise, detailed image of these formerly inaccessible sites. For artists, this meant no longer having to lug all of their gear up and down valleys and peaks which, as some of the images in the exhibition reveal, must have been quite an experience in itself.

Imagine, for example, the effort involved in capturing Gabriel Loppé’s enthralling and terrifying glaciers and crevasses in his “View of Mont Blanc” (1896). Meanwhile the non-traveling public, thanks to early projectors and machines such as the stereoscope, could now admire in their own homes images of places they had never seen in person. Visitors to the Newark exhibition will be able to experience and think about the benefits and uses of this technology, thanks to working reproductions of these types of Victorian gadgets.

A Perfect Opportunity for Self-Education

“The Rockies and The Alps” is exactly the sort of resource parents and teachers might consider to provide a deeper kind of learning. Many families cannot or wouldn’t want to drag all of the kids on a trip to the Alps or Rockies. Loading all of the fledglings into the minivan, however, while not an entirely stress-free operation, is more feasible. Moreover, institutions committed to ongoing public education like the Newark Museum are not only happy to have families visit, but already organize special tour days and events specifically designed for young minds.

Homeschoolers of course, find themselves in a slightly different situation than most parents of school-aged children. While most schools organize regular museum field trips, homeschooled children are dependent on their parents’ initiative and awareness.

Yet not all of the burden can or should fall on their parents, and museums need to be aware of the homeschooling trend. Homeschooling is expected to continue growing in coming years, with recent U.S. Department of Education figures indicating an increase from 850,000 homeschooled students in 1999 to more than 1.8 million homeschooled students in 2012.

This provides cultural institutions both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge lies in how to reach parents, so they can learn of and bring their children to educational events surrounding exhibitions and permanent collections.

There is also an opportunity here for towns. The idea, for example, of organizing specific days for homeschoolers in a county or metropolitan area to visit a particular museum would not only allow home educators to spread the word among their peers, but also allow homeschooled students to meet and interact with one another.

A Cool End to a High Ride

After the heights literally reached by many of the works in this show, it was almost a relief to come down to one of the last pieces in the exhibition, which is in the permanent collection of the Newark Museum. “Camping Near Lake O’Hara” (1916), a beautiful watercolor by John Singer Sargent, depicts a stylishly dressed couple languidly sprawled outside their tents in the Canadian Rockies.

Here there are no mountains to be seen, only a dense forest of pine and a bit of meadow dotted with wildflowers. Just as the couple are enjoying the cool mountain air, so too we can savor this image as a kind of sorbet, after the intense flavors that we have experienced in the exhibition to this point.

I particularly liked that the Newark Museum’s show is more than an art exhibition. The art itself is wide-ranging and fascinating, mixing familiar names such as George Catlin and Frederic Remington with artists who are relatively unknown to contemporary American audiences. We also have the tactile experience of Victorian photography to quite literally play about with, as well as scientific geological and botanical specimens collected from these mountain ranges.

“They give meaning and context” to the locations depicted in the art, Coleman pointed out, bringing home the notion that both to these artists and their patrons there was more going on in the depiction of these mountains than simply recording their appearance. The end result is a holistic exhibition that offers an engaging, educational experience, and aesthetic pleasure.

“The Rockies and the Alps: Bierstadt, Calame, and the Romance of the Mountains” is on view at the Newark Museum through August 19, 2018.

This article has been corrected with respect to Bierstadt and Calame’s relationship (colleagues, not friends), and the right prepositions in the exhibit’s title.