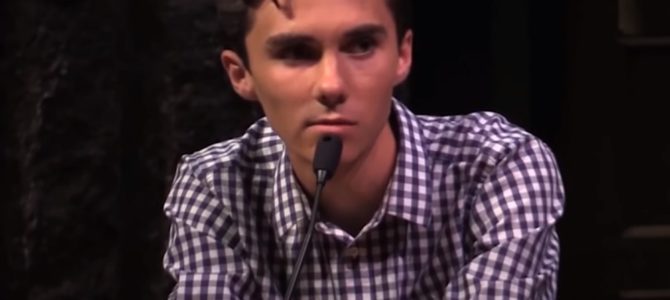

Gun-control activist and Parkland student David Hogg just announced the catchy title of his new book, billed as a rallying cry for his generation: “#NeverAgain.” If this sounds familiar, it should.

For several decades, the slogan has served as an international pledge never to allow another Holocaust. Emblazoned in five languages at the Dachau concentration camp memorial, the phrase is perhaps best known as the cri de coeur of late Auschwitz survivor and Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel.

I believe Hogg meant no offense in borrowing the slogan for his political cause, but it is chilling—particularly to have claimed it so blithely, without remark, at a time when knowledge of the Holocaust is fast fading among his generation. Two-thirds of millennials have never heard of Auschwitz and 22 percent can’t say what the Holocaust was, according to a recent survey.

Does it matter? I’m Jewish, so the Holocaust is an intimate part of my history, a way of explaining to my children what happened to all the family who never made it to America.

Of course, there is no one “official” version of history Americans “must” know. Still, there are enough historical omissions in millennials’ knowledge base to warrant concern. A third of millennials believe more people were killed by the George W. Bush administration than under Joseph Stalin, for instance.

Sounds like a punch line, but it isn’t. This isn’t a matter simply of failing to grasp one fact or another. It’s an omission of a broader kind—a vast canyon where basic knowledge should reside. It’s a troubling hint that outright lies, alarmism, and conspiracy theory may have corrupted the next generation’s mental files regarding the 9/11 years and eras prior.

Passions, they possess. Opinions, they wield. It’s the historical context they seem a little light on.

Forget Knowing Stuff, That’s Passé

For decades, so-called educators have downplayed what they derisively refer to as “rote memorization” and “content knowledge.” In place of the “Three Rs”—reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic—educators emphasize “Four Cs”: critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity. In line with the Common Core, these modern approaches, “deemphasize memorization and more strongly emphasize critical thinking and problem solving,” according to the National Education Association’s “Educator’s Guide.”

You might be tempted to wonder: How can anyone think critically without a store of facts to think critically about? But your question would be passé. According to a 2007 study sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, “habits of mind” such as “analysis, interpretation, precision and accuracy, problem solving and reasoning” are at least as important as “content knowledge” in determining college success.

In our Internet-infused era, a surplus of facts has led to a drop in price, a correspondence I knew to expect since I memorized the handy rule in a college economics course. The corner of my brain that faithfully stores the preamble to the Constitution, along with several passages from Shakespeare, could perhaps have been put to better use. Not since I’ve needed to rouse teammates for a soccer game has the St. Crispin’s Day speech brought me much use.

The Internet ushered in a much-hailed “democratization” of access to information, but with regard to our once-honored expert sources, the result was closer to a coup d’état. Experts who once held rarefied sway over matters of science and history now share quarters with loony toons. Students look to the Internet to settle every manner of inquiry, scholarly and trivial, fact and opinion. It’s easy to see how “What are the Federalist Papers?” can seem no different in kind from “Who makes the best burrito in Philly?” Both can be dispatched by crowd-sourcing.

Thanks to this approach, pediatricians have spent a decade battling nonsense science peddled by the likes of Playboy alumna Jenny McCarthy. Her anti-vaxxer activists still congregate on the Internet, where they brew up falsehoods and a resurgence of measles. In the Internet era, 9/11 was either a national tragedy caused by Islamist suicide bombers, or a conspiracy of the Bush administration, depending whose “truth” an Internet searcher wishes to believe. Holocaust scholars wrangle as status-equals with Holocaust deniers, if only by dint of shared virtual real estate.

The Only Answer Is Fact-Filled History Instruction

NEA-approved educators might argue the trick is to teach kids how to determine which sources to trust. But as Jordan Peele’s use of artificial intelligence to ventriloquize an astonishingly realistic avatar of Barack Obama shows, sifting pyrite from gold can be a fool’s errand. Even if we could all agree which sources to trust, this would lend troubling power to a few coronated sources. Think Walter Duranty, esteemed Moscow bureau chief of the New York Times, who won a 1932 Pulitzer for reports of the U.S.S.R. infested with Stalinist propaganda.

There are many reasons our young people need to know history—and not because those who don’t are doomed to repeat it. We’re all doomed if any of us is, for the simple reason that none of us can wholly escape our times. The reason to know history is simply that if you don’t, you’re far more susceptible to believing in lies.

Perhaps for this reason, millennials’ views reminisce more of Dark Ages than Enlightenment. Only two-thirds are confident that the earth is round. Forty-one percent believe—along with many notorious Holocaust deniers—that two-million Jews or fewer died in the Holocaust.

If you know nothing of the Nuremberg laws, the Wannsee Conference, or the crematoria of Auchwitz, it might seem reasonable to call any American politician you dislike a “fascist” or “Nazi.” Paranoia and conspiracy can offer tempting camaraderie for those without facts to guide them.

But unlike so many cultural trends, this one needn’t be cause for despair. We have already begun an overdue awakening to the societal dangers of pervasive misinformation. If we want the know-nothing pendulum to swing the other direction, our educators need only deliver it a hard knock.

Stop deriding factual knowledge; we need our young people armed with it. Stop teaching students that passion suffices for depth. And we should all stop permitting ourselves the deception that we know the information the Internet contains. If we do this, our aspiring critical thinkers might begin to sound more like sober citizens than common crackpots.