Before “Top Chef” and the “Great British Baking Show,” there was the Campbell’s soup company’s test kitchen. It was there, in 1955, that home economist Dorcas Reilly of New Jersey created an iconic American dish that will grace our tables all holiday season: the green bean casserole.

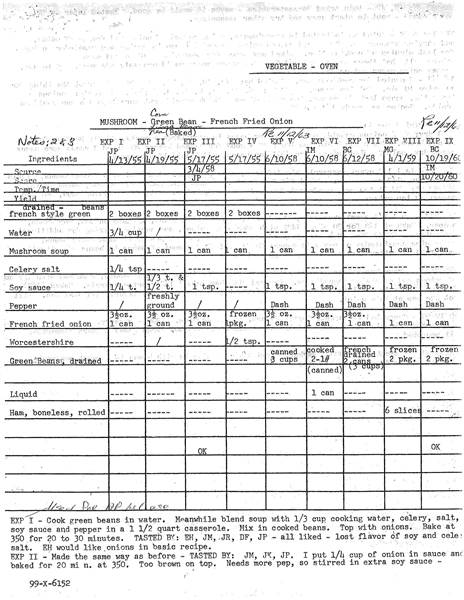

Originally dubbed the “Green Bean Bake,” Reilly devised it with the idea that many Americans would have its handful of ingredients already in their homes. Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom soup had already become a staple for casserole-making, particularly in the Midwest, where the dish retains disproportionate popularity.

Reilly added green beans, black pepper, milk, soy sauce, and finally fried onions to brighten up an otherwise gray-ish dish.

These days, Campbell’s estimates that almost half of the cream of mushroom soup the company sells goes to green bean casseroles. Reilly has been honored for her invention by her alma mater, Drexel University, and the National Inventors Hall of Fame, to which she donated the original recipe in 2002. Reilly tested four new twists on her original dish for Campbell’s just last year.

While being honored by her sorority in 2011, Reilly spoke about her dish and how it came to be, describing the testing process at the Campbell’s kitchen, where she worked with a group of five to seven other women. It reads like a precursor to the reality cooking shows of today. Reilly said the home economists got assignments from Campbell’s for specific promotions or cookbooks: “We’d discuss it and then we’d pick one person to go out into the kitchen and work.”

The cook meticulously kept track of all her ingredients, measurements, and methods, and when she thought she had a dish that worked, the rest of the team would be invited to try it. But this was no social gathering. This was serious business.

“[We’d] sit quietly around a table, and be served a portion of it, and then we’d score it,” without discussion, Reilly said.

Anything below a score of four was immediately sent back to the drawing board. Fives, sixes, and sevens were getting close to the standard.

“If it got an 8, boy, that was a real winner. That’s what everybody aimed for.”

After a score was announced, everyone in the group got a chance to suggest something to improve the recipe. It was retried and taste-tested again and again until it achieved a perfect score.

And what about the now-legendary “Green Bean Bake?”

“I don’t think ever that I remember that a recipe came through with a top score on the first try,” Reilly said.

In another element reminiscent of today’s reality cooking competitions, the home economists of Campbell got to travel to New York to perform live, high-stakes recreations of their recipes during commercial breaks on broadcast television.

Reilly described a set with two electric burners and a mock sink. She’d do a rehearsal in the morning and then go live in the evening. But because the food had been in the studio most of the day, she said, they’d occasionally have a bit of a fly problem by the time the live broadcast began. To combat this problem, her method was simple but not always effective: “Spray and pray” that no bugs would make it into the frame while she was on.

Now, that sounds like a challenge Tom Collichio might want to toss at his contestants next season. Reilly can be a guest judge.