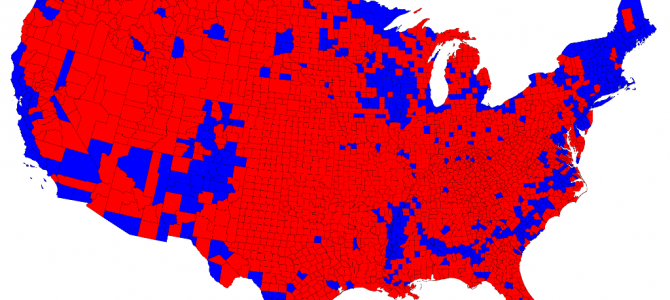

During the 2016 election, Donald Trump’s supporters frequently invoked the specter of Democratic political unity as a way of cutting short conservative arguments over policy. “How can we possibly win against the left if we waste all our time arguing among ourselves?” they asked. “The Democrats have a policy agenda they’re hell-bent on implementing; do you see them endangering that by fighting one another?”

In reality, the American left is as fragmentary as the right—and never more so than in the wake of the catastrophic 2016 election, which left Democrats shell-shocked and out of power at precisely the moment they felt would be their greatest triumph. Donald Trump was the most manifestly unfit candidate ever to run for president, they muttered to themselves; how could success possibly have eluded them?

Many liberals, including practically the entire mainstream media, have since chosen to live in denial rather than grapple with electoral failure, clinging to stories of Russian hacking, email meddling, and American bigotry to explain the 2016 election. Some, however, see that the party is reeling, and are sounding the alarm that Democrats must make big changes before it’s too late.

A Frustrated American Liberal

One such Cassandra is Mark Lilla, who sprang into the post-election conversation with a November New York Times essay entitled “The End of Identity Liberalism.” In it, Lilla argued that a single-minded dedication to identity politics—“a kind of moral panic about racial, gender, and sexual identity”—was killing the left at the polls. A new vision for politics is needed, Lilla argued: one that projects an image of a society that draws us together as citizens rather than pushing us apart.

Lilla has fleshed out his argument in book form. The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics is the attempt of a “frustrated American liberal” to diagnose the broad pathologies of American politics on both the left and the right, and to offer a blueprint for future liberal success.

To begin, Lilla gives us a story. The greatest seismic political event of the early 20th century was the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose dedication to the “Four Freedoms” (freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear) supplied the nation with a new framework through which to view politics as a vast cooperative effort to secure dignified lives for every citizen. This vision, which Lilla terms “the Roosevelt Dispensation,” provided the fuel for the vast liberal gains of the mid-century, from the New Deal to the civil rights movement to Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society.

But as technological and societal changes alienated Americans from one another in the 1960s and 1970s, a new zeitgeist reared its head. Ronald Reagan told Americans that the government was a bloated bureaucracy that stifled Americans even as it professed to help them. Americans didn’t need vast governments to succeed, Reagan beamed; they just needed it to get out of their way. This “Reagan Dispensation,” Lilla argues, championed the hard work of the self-reliant individual and the capitalist economy he could work his way up through. Government—“not tyrannical government, or inefficient government, or unjust government,” but government itself—was the problem. The Reagan dispensation was anti-politics.

To Lilla, Donald Trump’s victory in the Republican primary on a national populist platform signaled that dispensation was spent. But then a funny thing happened: Donald Trump won the general election too. The left had no vision that could rise to take the Reagan dispensation’s place.

Pseudo-Politics

What they did have, Lilla argues, is a “pseudo-politics.” In the wake of the Reagan Dispensation, the left retreated from the public square to the university and from the factory-dotted heartland to the urban coasts. Growing bored with tedious and difficult electoral politics, with its coalition-building and compromise, the left instead fell in love with politics as social movement, stressing fanatical devotion to the cause, severe ideological purity, and—worst of all—the notion that the only truly important politics were the ones that had personal meaning to the individual.

“The conviction got rooted that the movements most meaningful to the self are, unsurprisingly, about the self,” Lilla writes, quoting the 1977 manifesto of the feminist Combahee River Collective that “the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression.” That idea latched onto America’s college campuses, and it hasn’t let go since:

The study of identity groups now seemed the most urgent scholarly/political task, and soon there was an extraordinary proliferation of departments, research centers, and professorial chairs devoted to it. In part this has been a very good thing. … But it has also encouraged an obsessive fascination with the margins of society, so much so that students have come away with a distorted picture of history and of their country in the present—a significant handicap at a time when American liberals need to learn more, not less, about the vast middle of the country.

Imagine a young student entering such an environment today—not your average student pursuing a career, but a recognizable campus type drawn to political questions. … She will first be taught that understanding herself depends on exploring the different aspects of her identity, something she now discovers she has. An identity which, she learns, has already been largely shaped for her by various social and political forces. This is an important lesson, from which she is likely to draw the conclusion that the aim of education is not to progressively become a self through engagement with the wider world. Rather, one engages with the world and particularly politics for the limited aim of understanding and affirming what one already is.

What began as a political philosophy is now closer to a religion, complete with ornate speech codes, baroque hierarchies of accepted and censored voices, and frantically enforced moral norms. In such a system, Lilla fears, the student will become incapable of understanding those outside her narrow political horizons: “Her political interest will be real but circumscribed by the confines of her self-definition. Issues that penetrate those confines now take on looming importance and her position on them quickly becomes nonnegotiable; those issues that don’t touch on her identity are not even perceived. Nor are the people affected by them.”

The Disingenuous Embrace of the Trump Voter

Conservatives, of course, have been sounding the alarm for years about the insanity of of the growing identity politics movement, and any introspection they can get from the left is music to their ears. This explains why many on the right, most notably Rod Dreher, have latched onto Lilla’s book. And although leftist insanity is surely a political boon for American conservatives in the short term, having a reasonable opposition party is certainly far healthier for America in the long term. So does Lilla provide a viable path away from pseudo-politics for the left?

Unfortunately, no. Because Lilla has a problem: Hitting the bullseye on identifying the left’s problems does not amount to providing a viable solution. And for a book that’s ostensibly about what comes “after identity politics,” Lilla’s vision of the future is remarkably thin.

Lilla begins his prescription well, urging leftist elites to “descend from the pulpit” of sanctimony to actually meet their political bogeymen—the rural poor whose “whitelash” of racial and class animosity supposedly propelled Trump to the White House—as human beings. On this topic Lilla is almost lyrical: “Learn to listen and imagine,” he urges. “You need to visit, if only with your mind’s eye, places where Wi-Fi is nonexistent, the coffee is weak, and you will have no desire to post a photo of your dinner on Instagram. And where you’ll be eating with people who give genuine thanks for that dinner in prayer. Don’t look down on them.”

This is a commendable statement and critical advice for the modern Democratic party. But Lilla undercuts it pages later with his description of the average Trump supporter:

Anyone who watched a televised Donald Trump rally in the 2016 campaign was witness to a mob orgy, not an assembly of citizens. … Whatever might be said about the legitimate concerns of Trump supporters, they have no excuse for voting for him. Given his manifest unfitness for higher office, a vote for Trump was a betrayal of citizenship, not an exercise of it.

What gives here? How can Lilla simultaneously urge his reader to empathize with the concerns of the Trump voter and assure him that none of those concerns justified their decisions?

Getting Beyond the Partisanship

The answer is depressingly simple. For all his insights about the pathologies of the modern left, Mark Lilla has not divested himself of the most ubiquitous intellectual quirk of today’s establishment liberal: He equivocates the common good with the electoral success of the Democratic Party. Lilla is not trying to convince leftists that they stand to learn anything from voters in Appalachian West Virginia or rural Missouri. He’s just trying to convince them to be able to stand their presence long enough to win their votes.

This can be seen in Lilla’s infantilizing prescriptions for real political action. Do Trump voters have valid political concerns? Maybe, but the real problem is that they’re acting out because they’re tired of being yelled at. “Children do not respond well to scolding and neither do nations,” Lilla writes. “They become better only when they are told that they are already good and therefore can improve.”

A yet more jaded analogy is that of the fisherman: “When you fish you get up early in the morning and go to where the fish are—not to where you might wish them to be. … Once the fish realize they are hooked, they may resist. Let them; loosen your line. Eventually they will calm down and you can slowly reel them in, careful not to provoke them unnecessarily.”

With such wheedling, Lilla hopes to transform leftist hatred for the Trump voter into either mere dislike or paternalistic condescension. They may be backwards, bigoted hillbillies propelled by racial and class resentment, Lilla admits, but we need those hillbillies’ votes. In the end, Lilla’s prescription is nothing more than an acknowledgment that Democrats need to adjust their electoral strategy. In 2016, Chuck Schumer maintained that “For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs of Philadelphia.” No such luck, Lilla says. We need those blue-collar people, and we might as well get used to it.

Conservatives should commend Lilla’s willingness to turn a critical eye on his own movement and party to discuss the grievous problems of American universities and the identity politics that have choked them. But he ultimately misses the point by assuming that the worst that will come of those universities is damage to Democrats’ political chances. As radical identity politics continues to roil places like Berkeley and Evergreen, more liberals may begin to call for real changes. Let’s hope they do so in a more meaningful way than The Once and Future Liberal.