We met our wedding photographer at our neighborhood coffee shop on a busy Sunday morning in January.

“What brings you all the way out to D.C.?” I asked her.

“I came into town for the Women’s March on Washington!”

My face struggled for a second trying to keep my eyes from rolling up to the ceiling. I had spent the previous day inside, hiding from the temptation to confront every pink p-ssy-hatted woman who passed me on the street. My fiancé and I had titled our engagement announcement Make Marriage Great Again, so I thought it might be best to keep my mouth shut.

“That’s cool,” I finally offered.

As we talked, however, I saw how passionate she was for the art of photography and for telling the story of our budding relationship. She would, after all, be responsible for creating the most important physical link between our future and that single day when we committed our lives to each other forever and ever, amen. So we put down a deposit.

Artistry Is Far More Personal Than Delivering Goods

We cut checks for many things for our wedding: the reception hall, the limo, flowers, food, and, of course, the booze. But as important as booze is to a big German-Italian wedding, there was a noticeable difference between calling up the local liquor store for a flatbed delivery of the good stuff and the meetings we had with the photographer, the cake baker, the reception hall owner, and my aunt, the florist, who has the most vibrant green thumb you ever saw.

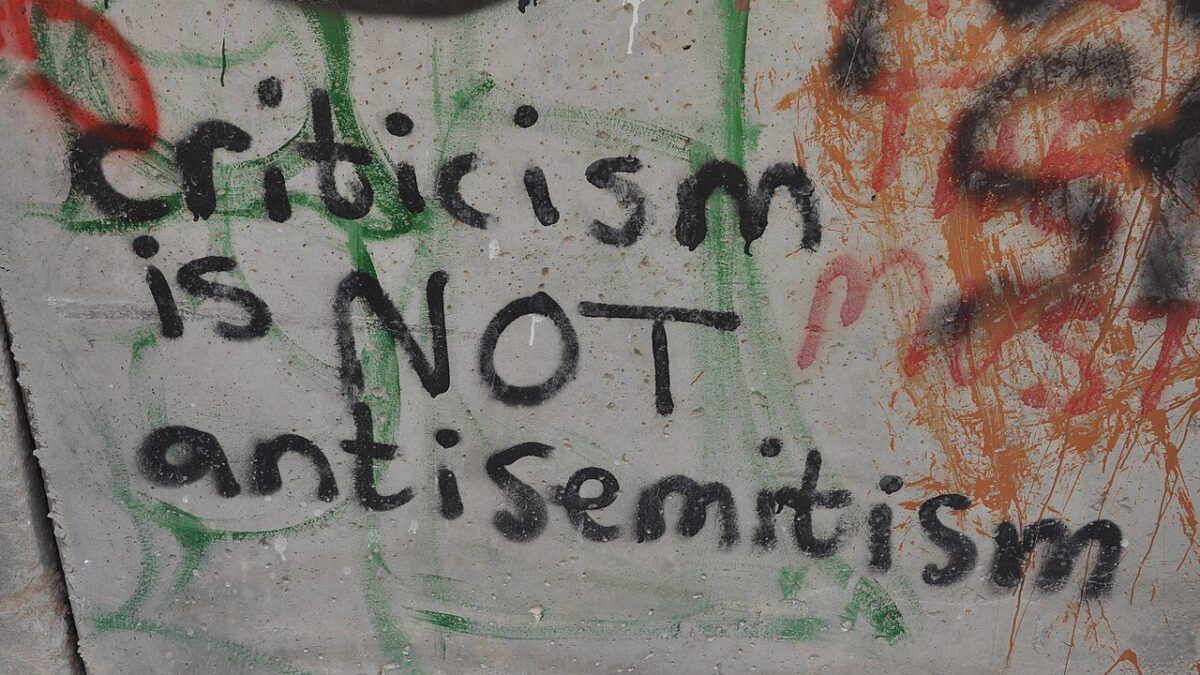

Debate over laws such as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and the First Amendment Defense Act (FADA) is often reduced to a battle of rhetoric: is refusing to actively participate in or offer certain services to a wedding ceremony for LGBT persons an exercise of religious conviction, or is it merely a license to discriminate against them?

This is the central question of a case the Supreme Court has just taken up, involving a Christian baker in Colorado and a same-sex couple who requested a custom cake to celebrate their wedding.

I’ll lay my cards on the table. I do believe we need a balancing test between a citizen’s religious concerns and the sometimes conflicting interests of the state, and I’m open to arguments that proposed policies could be tweaked to create a truer test. I have always supported these policies intellectually. After interacting with the kinds of people they’re meant to protect, however, I realized that we need a deeper commitment to protecting the artists that photographers, bakers, and florists are.

Let’s All Step Outside Ourselves and Have Compassion

What planning my own wedding showed me is how hard it is to imagine anyone else’s concerns but my own. This is a sign that the freedom allowing us to be a truly liberal society — the freedom to disagree — is eroding faster than you can say “bigot.”

I will never know what it would be like to look through my photographer’s portfolio, to fall in love with her use of light and shadow and perspective, only to be told that I would have to find someone else. I hope I can have compassion for those who do experience this.

At the same time, I ask those who call religious freedom a “license to discriminate” to imagine the difference between purchasing alcohol and compensating another person for using her artistic, transcendent, and uniquely human creativity to help celebrate a marriage.

There were so many times throughout wedding planning that I simply deferred to my photographer, florist, baker, and reception host because I didn’t want to inhibit the artistry that seemed to just flow from their skilled hands and fertile minds. Interacting with them was a highly personal matter, much more so than the simple exchange of goods.

Art Comes From the Soul, and Should Never Be Compelled

We all need to bring more imagination to the public square because it is not access to these things — cake, flowers, pictures — that is up for debate, but the incredible capacities that we have as human beings, and the freedom that allows us to develop our talents in accord with our morality. To sue these artists out of business, frankly, is political censorship of art, and we should be terrified that this happens in America.

I’m sure I disagree politically with my photographer. Maybe she doesn’t see any problem with gay marriage. That’s the norm for my generation now, and supporting gay weddings has been integrated into most of my peers’ moral code. I know photographers who are deliberately making an effort to photograph more gay weddings, and they should have the freedom to do that. But either way, I don’t want my heady opinions — aesthetic or political — disrupting how my photographer practices her art.

There really are photographers, bakers, and florists who value marriage between a man and a woman as a human participation in divine creativity. Just as our photographer took a special interest in our relationship at least in a humanist way, other artists participate in weddings in a religious way, using their creative talents to help couples fulfill a piece of God’s plan. What has our society become if we will not let them do that?