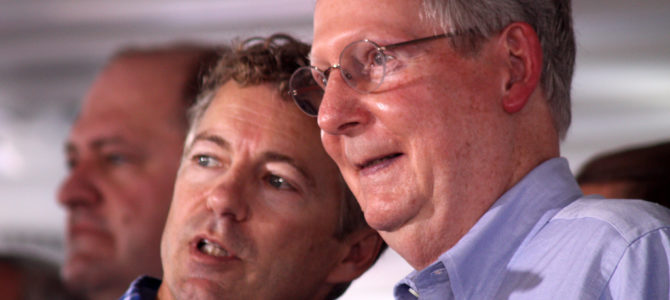

As the Senate attempts to develop its version of Obamacare “repeal-and-replace” legislation, lawmakers have floated a lengthy phase-out of the enhanced federal match associated with Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion. Reports indicate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has suggested a three-year phase-out running from 2020 to 2023, while Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH) and others have suggested a phase-out that would continue until 2027.

Discussion of both proposals to date has omitted one key fact: Implementation of either phase-out plan—and thus scaling back a major part of Obamacare, on which Republicans have run the past four election cycles—hinges almost entirely on Republicans winning another presidential election. In the case of the Portman plan, it would also hinge on continued Republican control of the White House following the 2024 election.

If Republicans do not retain the White House in 2020, it’s highly unlikely that the tens of millions of able-bodied adults Obamacare added to Medicaid will ever transition off the program rolls.

Incentivizing States to Run Out the Clock

While neither McConnell nor Portman have released bill text (or even legislative specifications) for their respective proposals, it seems likely that each would use a phase-down approach to the enhanced Medicaid match. Rather than keeping the enhanced match at 90 percent for several years then dropping it down to the regular Medicaid match rate (which ranges from 50-74 percent this year), the proposals would likely ratchet down the match rates a few percentage points at a time each year—say, from 90 percent to 85 percent to 80 percent, and so on until reaching a state’s regular match rate. This gradual phase-down would require less spending than extending the 90 percent match to 2023 (or 2027) and creating a one-year cliff as the rate drops to the regular match level.

But if the federal match only begins to slow down in 2020—and slows down gradually at that—states that adopted the Medicaid expansion would have little incentive to start phasing people off the rolls, instead waiting to see the results of that fall’s presidential election. States would only have to pay a slightly higher match rate, and only for a portion of their Medicaid expansion, because the House-passed bill allowed states to continue receiving the 90 percent match for enrollees in Medicaid as of December 31, 2019 who remain continuously enrolled.

Under this scenario, the cost to states to retain their expansion in 2020 would rise, but not appreciably—by tens or hundreds of millions, depending upon the state’s size, but certainly not by billions. Many states, particularly “blue states,” would pay this added cost, at least for one year, as the price to see what happens on November 3, 2020.

If results go poorly for Republicans on that day, then a new Democratic president—along with Republicans who never wanted to end the Medicaid expansion in the first place—would likely act quickly to undo this provision and much of the rest of whatever “repeal-and-replace” legislation Congress can enact this year. Democrats could easily enact legislation undoing the Medicaid phase-out early in 2021, before most of the phase-out the McConnell and Portman plans envision would even have gone into effect.

Accelerate the Transition

For all these reasons, it seems dangerous to wait two-and-a-half years, until the brink of the presidential election cycle, to start the transition away from the enhanced Medicaid match. Granted, some states do have triggers ending the Medicaid match immediately if said match rate ever falls below 90 percent. But it would be perfectly reasonable to give state legislatures several months to adjust their laws to the new policy environment, while beginning the transition at some point in 2018.

Moderates wishing to keep the Medicaid expansion should keep in mind that all but two members now serving voted for repeal legislation in 2015 that ended the expansion completely—not just the enhanced federal match rate, but also categorical eligibility for low-income adults—after a two-year transition. Conservatives have already made major concessions, first by including “replace” provisions on the “repeal” bill, and second by allowing the expansion to continue, albeit at the traditional Medicaid match rate.

Having promised voters for more than seven years they would dismantle Obamacare, Congress shouldn’t kick the can down the road and hope that some future Congress will keep an earlier Congress’s word and actually let provisions undoing the law go into effect. In stating that a further postponement of the Medicaid transition beyond 2020 would jeopardize passage of the legislation, the Republican Study Committee points at an important truth.

Conservatives should stand fast to the promises of repeal—and members’ own voting records—by insisting that Congress complete the transition away from the enhanced Medicaid no later than the end of this presidential term.