Commercials have never been the same since 1966, when Stanley Kubrick hastily assembled a music track for the unfinished film “2001: A Space Odyssey.” With film production running years behind schedule, Alex North’s score incomplete, and impatient Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer executives in need of mollification, Kubrick borrowed music to temporarily accompany a few scenes for a progress report. He opened with several bars from composer Richard Strauss—and became so attached to them that when the movie finally appeared in 1968, North’s score had been flung to the breeze.

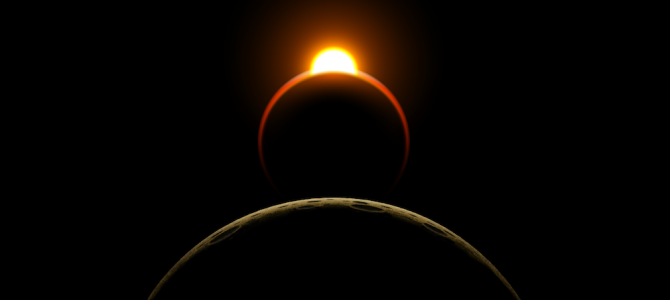

The bars Kubrick utilized were a short prelude, titled “Sunrise,” to a nine-part, half-hour tone poem (a programmatic work in one movement that illustrates a story). It premiered in 1896 under the title “Also Sprach Zarathustra.”

Freed from the constraints imposed by a symphony (a four-movement work typically comprised of a sonata-form allegro, a slow movement, a minuet and trio, and a rondo finale), Strauss borrowed his title and various section headings from Friedrich Nietzsche’s work of the same name. He crafted a musical rendition of the story, in which a philosopher-prophet descends from solitary contemplation on a mountaintop to share his wisdom with mankind. But unlike other tone poems such as Strauss’s “Don Quixote,” in which the music is closely tied to the character and story it represents, the links between Nietzsche’s work and Strauss’s music are nebulous.

The Story Behind Strauss’s Nietzsche-Inspired Composition

Subtitled “Tone Poem (freely after Friedrich Nietzsche),” Strauss’ “Zarathustra” has been a source of some angst for those who wish to interpret it. Do the musical sections depict corresponding parts of Nietzsche’s work, or are the borrowed chapter headings just guideposts for the composer? The general view as to the former is no; consensus decidedly wobbles over the latter.

It’s unknown to what degree Strauss attempted to paint Nietzschean ideas in sound. The composer disavowed that he was writing philosophical music or merely presenting an instrumental version of the book, but simultaneously alleged that he was trying to portray human evolution from the beginning to Nietzsche’s Übermensch.

When Kubrick borrowed these opening bars from Strauss, it is doubtful he knew much about the piece—or realized the effects his use would have. According to his brother-in-law and “2001” executive producer Jan Harlan (as recounted in Christine Gengaro’s book “Listening to Stanley Kubrick: The Music in His Films”), Kubrick’s search parameters for the film’s title music were the pinnacle of profundity: “something big that comes to an end.”

“Zarathustra” aptly fit the bill. Its 21 opening measures rise out of the silence, building from almost inaudible low Cs in the contrabassoon and organ into a glorious cadence powered by the united force of the entire orchestra and blazing pipe organ. Thanks to the movie, these bars soon became one of the most recognizable pieces of ad music: its epic, heroic notes used over and over to sell everything from cars to Pop Tarts to iPhones.

How ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ Hijacked ‘Zarathustra’

Its appearance in “2001: A Space Odyssey” dramatically changed both the presentation and reception of “Zarathustra.” Prior to Kubrick’s appropriation of the tone poem (or hijacking, as it has been aptly described), its popularity leant to the negative. Up against the stiff competition posed by Strauss’s other tone poems—the virtuosic “Don Juan,” dark “Death and Transfiguration,” merry “Till Eulenspiegel,” fantastic “Don Quixote,” and necessarily epic “Ein Heldenleben,” “Zarathustra” fell by the wayside. The audience appeal was not as strong. Most of the musical lines were easily forgotten.

But this once-neglected tone poem has become Strauss’ most recognizable work and, according to musicologist John Williamson, has changed “from a dance of Dionysian life-affirmation … to something altogether more grandiose.” The change in perception, Williamson notes, is “partly the story of the revenge of Nietzsche’s ‘herd.’” The music earned a mass audience only as its original title lost its force and received a new (though not necessarily accurate) public image.

Its popularity grew in leporine fashion as “2001’s” soundtrack spent 36 weeks on the Billboard classical charts, and everyone (even Elvis Presley) wanted to cash in on the possibilities it raised.

The opportunists reportedly included Decca Records, which provided Kubrick with “Zarathustra” via a Vienna Philharmonic and Herbert von Karajan recording. Apprehensive of the possible tarnish to its reputation this stoop to pop culture might cause, Decca Records requested exclusion from the credits—then shortly began scrambling to redirect pop culture’s devoted followers to the proper source.

Today, conductors and audiences have a hard time separating “Zarathustra’s” opening bars from the spatial vastness of “2001’s” opening credits. They expect, and obtain, the epic. Its new descriptive catchphrase is “monumental.” Never mind that after the first 21 bars, almost no one recognizes the piece—neglect so severe, even those who ought to preserve the work in its entirety succumb to the temptation to dismiss it. (I once played in a music-from-the-movies concert, where the program was to include “Zarathustra.” During the first rehearsal, at about bar 30, the slightly bewildered conductor set down his baton and said that since the audience would not recognize anything past the opening, we would only play those 21 bars.)

Today’s ‘Zarathustra’ Is About Pop-Tarts and Hummers

Perhaps inevitably, the next effect of “Zarathustra’s” popular transformation was its penchant for appearing in all sorts of illogical places. What was written as a tortured Nietzschean musical masterpiece, has become—at best—the new theme song for space exploration and cutting-edge technological inventions, at worst an overused commercial jingle. Unless, that is, Nietzsche and Strauss envisioned that ice-cream-filled Pop-Tarts, Hummers, and even butter are a laudable component of human evolution or necessary to reaching the Übermensch.

Long gone are the contemplative evocations of the human condition, or the hints of long-robed Zoroastrian priests—let alone any reference to that oft-spectacular yet quotidian occurrence called a sunrise. In modern performances, Strauss’s opening bars declare that what you are about to see is completely unprecedented and out-of-this-world amazing.

Movies hijacked classical music long before Stanley Kubrick came along—and some of the best-known classical composers of the early 20th century, such as Dmitri Shostakovich, were not abashed to compose for the cinema. Other classical masterworks have likewise been appropriated as clichéd commercial commentary—Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna” from “Carmina Burana” and Giuseppe Verdi’s “Dies Irae” from his “Requiem” immediately spring to mind. (Kubrick narrowly avoids blame for commercializing both of these: he was such a fan of the former that he had considered hiring Orff to score “2001.” Listening to the latter proves unendurable for an isolated astronaut in the novel written concurrent with the film.)

However, “Zarathustra” is perhaps unique among other classical masterworks subjected to the movies and commercials treatment. The thoughts and emotions it evokes are the product of its appearance in “2001,” not organic to the work as Strauss composed it. Furthermore, the very purpose for which it is used—portraying a product as an epic discovery, one possible only thanks to the extremes of scientific advancement—sells short the philosophical underpinnings of Strauss’ work.

Thanks to a film, “Zarathustra’s” opening trumpeted proclamation no longer heralds the arrival of a philosopher who has probed the foundations and purpose of humanity. The orchestral swell now totters toward a meaningless void, propped up by fleeting creations of food and metal bound for decay. Strauss and Nietzsche are largely forgotten, their audience unaware the ice cream was heralded by a sunrise, and the new car revealed by a priest emerging from a mountaintop retreat.