San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick launched a thousand hot takes recently in refusing to stand during the national anthem at a NFL preseason game. Some players supported him, others criticized the stunt. Sports writers delved into politics while political writers talked sports. Even the president put in his two cents.

This past weekend, the protest spread to professional soccer as U.S. Women’s National Team player Megan Rapinoe inexplicably exchanged the Flag Code for the Book of Common Prayer and decided she could “stand or kneel” during the anthem at a Seattle Reign game. She knelt.

The furor over Kaepernick has gotten Americans talking about free speech and the First Amendment. In that, at least, something good has been accomplished. The discussion breaks down into several overlapping categories. First: does the First Amendment protect Kaepernick’s protest? Almost everyone agrees that it does, but that does not mean as much as you might think. The First Amendment protects people from being punished by the government for their speech. In that, Kaepernick and Rapinoe are secure.

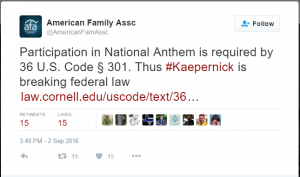

Various Internet law “experts” have debated even this fairly obvious bit of law. Consider this tweet (since deleted) by the American Family Association:

The AFA is right about one thing: the Flag Code exists. You may have learned about it in scouting or elementary school. It is a collection of rules about how people are supposed to treat the American flag. It is detailed and rigorous, but carries as much legal weight as Amy Vanderbilt’s etiquette books.

Even if the language of the law was not clearly a suggestion (“should,” rather than “must” or “shall”), courts have long decided that laws like the one the AFA imagines exists violate the First Amendment and are void (see, for example, West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette). Just as no one will throw you in jail for using the wrong fork, no one will throw you in jail for showing disrespect to the American flag.

Clearly, Kaepernick and Rapinoe won’t be sent to Guantanamo Bay for their lack of patriotic fervor. But can their employers punish them? This is a trickier issue. The NFL, in particular, has been known to fine players for all sorts of things that government would consider protected speech.

The NFL’s statement was brief: “Players are encouraged but not required to stand during the playing of the National Anthem.” The 49ers were equally unwilling to take sides, saying they “recognize the right of an individual to choose to participate, or not, in our celebration of the national anthem.” As yet, the NWSL and Seattle Reign have not commented on Rapinoe’s protest.

Free Speech for Some, Miniature American Flags for Others

The government may not punish them for speaking out, and their employers have declined to do so. But what about the people? In this, we are all free to decide. As usual, some consider being unpatriotic the highest form of patriotism. Even among those who love the flag, the anthem, and the republic for which they stand, some have jumped to Kaepernick’s defense. You may even have seen someone drag out that old line attributed to Voltaire (actually written by Evelyn Beatrice Hall): “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

Defending the right to unpopular speech, if not the speech itself, is the heart of free speech as a societal value. The Constitution says only the government will not punish people for their speech, but defending free expression is not required by law. When we do that, we do it because the marketplace of ideas has become a core part of the concept of democracy.

Tolerating differences of opinion has always been a part of the American character. This democratic spirit is what breathes life into the Constitution’s words. If we only had the words of the First Amendment without the societal value that goes along with them, courts would have long ago found a way to brush the words aside. Our freedoms in law are constantly reinforced by the idea, independent of the written law, that this is a free country.

A tradition of tolerance, though, does not require us to accept all behavior as equal, nor does it require us to agree with the speech we believe should be protected. Plenty of people have said they will boycott 49ers games and burn their Kaepernick jerseys. That is their free speech. Others will buy Kaepernick’s jersey in record numbers. That, too, is free speech (and a handy illustration of why, no matter which side they take, the NFL always wins).

When the Government Boycotts You

Boycotts get trickier when the people doing the boycotting are government employees. The idea has become more common lately that if government employees find some law objectionable, they may choose not to enforce it. Former Pennsylvania Attorney General (and current convicted felon) Kathleen Kane declared in 2013 that she would not defend her state’s marriage statute from constitutional challenge, despite that being the one of the main duties of her job. In 2015, Kim Davis, a county clerk in Kentucky, took the opposite side of that argument, refusing to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, despite the law of the land requiring that she do so.

In both instances, these state workers took their right to free speech and turned it into a new, imagined right: the right not to do your job (and still get paid). In the continuing Kaepernick drama, the Santa Clara Police Officers’ Association seemingly joined the side of the government boycotters. The consequences here are even more dramatic; the police cannot choose whom to protect based on their speech. On closer inspection, though, the SCPOA’s exact position is more complicated than Kane’s or Davis’s.

As local reporter Ian Cull explained on Friday, the union issued a statement stating that its officers might stop working at 49ers home games because of their disagreement with Kaepernick. Given that the 49ers’ home stadium is in Santa Clara, it sounds like the police are threatening to withdraw their protection from the arena, leaving it a stinking den of lawlessness. This is not the case.

In reading the full letter from the SCPOA to the Niners, it becomes clear that Calvin Coolidge can rest easy: the police are not on strike. They never were deployed at the stadium to begin with. Instead, the 49ers typically employ off-duty police officers to work as security guards when the team has a home game. Many of these officers are Santa Clara police officers and members of the SCPOA.

In that case, one might say that the Santa Clara officers are doing what rule-of-law advocates demanded of Kane and Davis all along: if you disagree with the job you’re hired to do, you should quit. These police officers are working a second job for an employer with whom they suddenly have reason to disagree. As a result, they expressed their disagreement through their union, and threatened to quit if the disagreement is not resolved. This is the free market at work, isn’t it?

It is, but it is not a simple as all that. Police unions, like all government employee unions, occupy a different place in American life than their private-sector brethren. If you disagree with something about the carpenters’ union, you can hire non-union carpenters—or, if you have a preference for union workers, you can hire only union carpenters. The market affords us that choice. No one is forced to join a union, and no one is forced to hire union (or non-union) workers. That same First Amendment guarantees the freedom to associate (or not associate) as we choose.

The same is not true with government worker unions. The nature of government is that there is only one of them at each level. Wherever you live, there is one municipal government for that place, one state government, and one federal government. You can move from place to place, but wherever you land, there is only one choice. When the government workers are unionized, they also have a monopoly, one the citizenry cannot avoid.

Looking at the SCPOA’s letter from this point of view, the closing paragraph seems more menacing: “The men and women of the Santa Clara Police Officers Association are sworn to protect the rights of ALL people in the United States, a duty we take very seriously. Our members, however, have the right to do their job in an environment free of unjustified and insulting attacks from employees of your organization.”

As far as the members’ second job at the stadium goes, this is true. But phrased as an absolute right, it makes the average citizen question the union’s commitment to non-discriminatory policing. Citizens should respect the police, who put their lives on the line to maintain order and safety in our communities. But the idea that they have a right to do their job without criticism—that anyone has such a right—is ludicrous.

Police officers have every right to disagree with Kaepernick’s statements and actions. Kaepernick, for his part, has the same right to disagree with the police. And while SCPOA members have the right to quit their second jobs as private security for the 49ers, their union should be careful about establishing a precedent that they have the right to work free of criticism. If they want to quit, they should quit, and let the 49ers hire new security guards. But they, and we, should also remember that the First Amendment runs both ways.