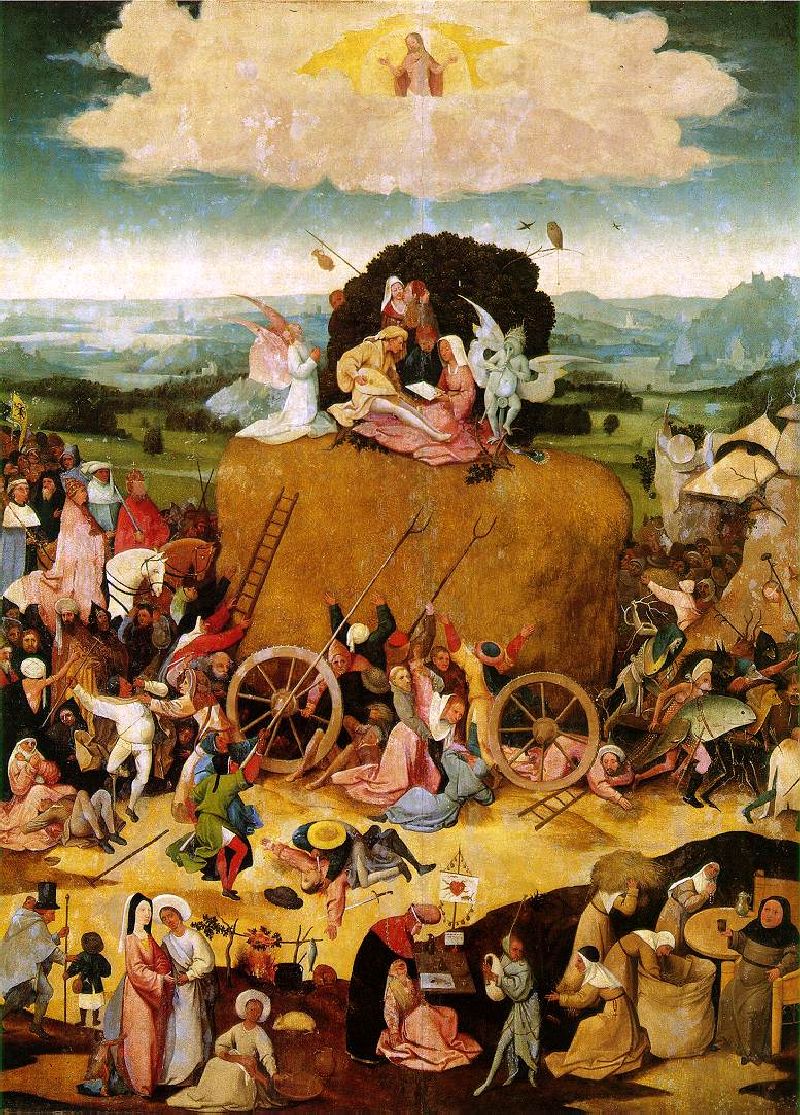

While audience participation is not unusual in many works of contemporary art, one rarely experiences the sensation of being a participant in the drama of an Old Master painting. When trying to get into The Prado to see “Bosch. The Fifth Centenary Exhibition” on its first day, however, I was reminded of the long procession of fools in “The Haywain” (1516), a triptych that appears in the show and remains one of Hieronymus Bosch’s best commentaries on man’s sinful nature.

Amidst the utter chaos of jostling tourists and insolent staff pushing each other about and spreading misinformation, at times it felt as if we were all just like the figures in Bosch’s altarpiece, clutching at the straws of a juggernaut rolling its way to Hell. While I attribute some of this disorder to opening day, visitors to The Prado would nevertheless be well-advised to give themselves extra time, should they wish to enter the museum with some scraps of basic human decency and self-composure left intact.

Upon entering the exhibition, however, the tortuous journey will be quickly forgotten. Without question, this commemoration of the work of Bosch (c. 1450-1516) on the 500th anniversary of his death is one of the best shows I have visited in some time. He may not be an artist to everyone’s taste, yet in his inventiveness and attention to detail Bosch remains one of the most fascinating painters who has ever lived, influencing princes and bishops, writers and philosophers, filmmakers and fellow artists right down to the present day.

A Grand Close-Up for Hieronymus Bosch

The sheer scale of this show is a curatorial triumph in itself. The exhibition contains almost every painting known or believed to be by Bosch, in addition to a number of works attributed to his workshop or followers, as well as a selection of related pieces from his time. Many of Bosch’s paintings have not survived, as those who found them objectionable destroyed a significant number during the Reformation.

Perhaps it may seem historically curious that so many of his pieces found a home in Spain, given both the influence of the Inquisition and the rather famously reserved standards of the Spanish court, but then again the tastes of the Habsburgs were hardly matters to trifle with. In fact, King Philip II of Spain loved Bosch’s work so much that several of the artist’s most famous paintings decorated the king’s otherwise-Spartan apartments in The Escorial.

The gallery containing the Bosch exhibition at The Prado is laid out in an almost serpentine fashion, so that the visitor follows a winding, roughly chronological path tracing the development of Bosch’s work. It was surprising to see how close visitors were allowed to get to the works, when so exhibition visits inevitably involve guards barking that one needs to step back. In designing this show The Prado must have understood that visitors will want to peer closely at the beasts and birds, angels and demons that came to dominate his work as he matured. Because these details are often tiny and cannot be easily observed at a distance, visitors have greater leeway than one might expect. There are also accompanying X-ray images in several instances, showing how the artist altered some finer details of the paintings as he painted them.

Even more surprising than the close scrutiny permitted visitors to the exhibition was The Prado’s decision to display some of Bosch’s most famous altarpieces on plinths of about altar height, echoing the original intent and placement of these objects. Rather than seeing these multi-paneled, hinged paintings flat on a wall, visitors can walk all the way around them, thereby appreciating these works of art from all sides.

As the museum explains, “the exhibition will encourage visitors to look deeper into his personal vision of the world through the spectacular installation in which Bosch’s most important triptychs are shown free-standing in order for both the fronts and backs to be visible.” Helpful photographs on the back of the central panels show what the split image would look like if the wings were closed, and the two back halves brought together.

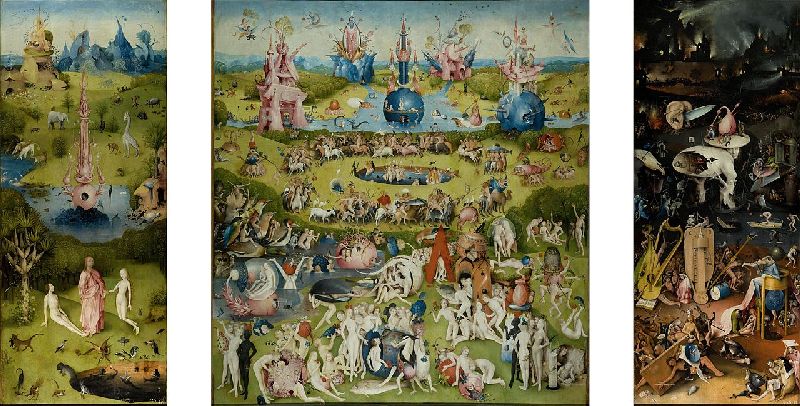

Attempting to Understand Bosch Through His Works

Sometimes these secondary images are clearly related to the subject of the central image itself, but sometimes we can only speculate as to why they appear. For example in Bosch’s masterpiece “The Garden of Earthly Delights” (c. 1503-1515), the familiar, colorful scenes of the creation of Eve, the pleasures of the flesh, and the punishments of the damned in Hell are accompanied on the reverse by an image in grisaille showing the third day of creation as described in the Book of Genesis. With the wings closed, mankind does not yet exist, and the universe resembles a pristine jewel. With the wings open, we see the progress of sinful man from his creation in an earthly paradise, to pursuing a life of pleasure-seeking, to the eternal punishment of the damned.

On the back of the delicate “Adoration of the Magi” (c. 1485-1500) altarpiece, on the other hand, we see a grisaille image of the Mass of Pope St. Gregory, an event in which Christ appeared during the Consecration at Mass to convince a doubter he is truly present in the Eucharist.

The connection between these two subjects is not immediately obvious. One could speculate that the visit of the Magi to the Christ child on Epiphany, i.e. his “manifestation” to the nonbeliever Gentiles, is echoed by Christ’s later manifestation of himself in the bread and wine of the Mass. Or it could be that the man who paid for the altarpiece was named Gregory, and he wanted a scene from the life of that saint incorporated into the work he had commissioned. We simply do not have enough information to know for certain.

This brings us to the thorny problem of trying to understand one of the most complex talents in Western Art. Because we know so little about Bosch’s life, and have no writings from him explaining his work, the paintings and drawings in this show are really the bulk of what we have to figure out who he was. The exhibition does an excellent job in sharing with visitors the basic facts we have about Bosch’s life, as well some of the folk customs, practices, and symbolism that was well-known in his day to provide greater context to the show. It also makes clear that Bosch was likely a well-read man, since many of his paintings reference works of literature that would not have been familiar to the average person.

Deeply Concerned with Religious Ideas and Symbols

To begin to understand Bosch through his art is, first and foremost, to accept that he was a deeply Catholic artist: if you do not understand this, you cannot hope to come to grips with his work. While he captured the public imagination painting horrific creatures and nightmarish places, his efforts were intended to warn rather than entertain. For a devout Christian such as Bosch, who was a member of at least one deeply pious religious fraternity dedicated to the Virgin Mary in his home town of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the damnation of unrepentant sinners to Hell was not an amorphous concept, but a reality. He clearly believed in the apostle’s warning in 1 Peter 5:8 that the Devil prowls about the world, seeking the ruin of souls.

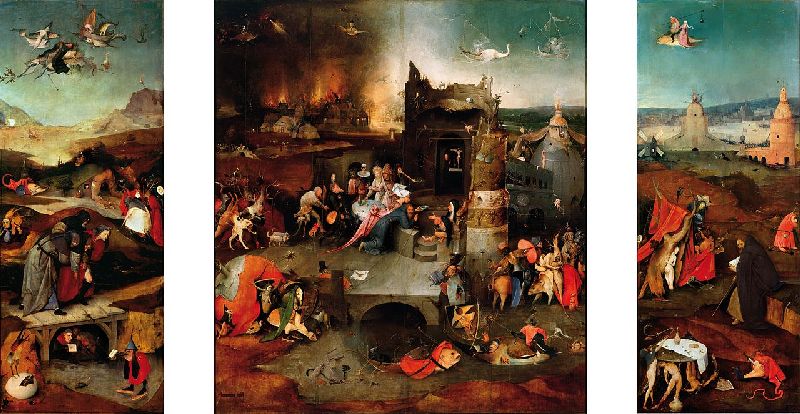

In studying Scripture and reading devotional works chronicling the lives of the saints, Bosch would have been very much aware that the great men and women of the church, and even Christ himself, were subjected to temptations and tortures of the flesh by the Devil and his minions. One saint whose sufferings Bosch revisited several times in his art was St. Anthony Abbot, a fourth-century Egyptian hermit known as the father of Christian monasticism. Several examples of the artist’s treatment of this subject are part of The Prado exhibition, including a recently authenticated fragment of a larger Bosch painting of St. Anthony, which was discovered in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri.

Perhaps my favorite example of this subject in the show is the “Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony” (c. 1501) from the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon. One of the best-preserved works by Bosch in existence, this altarpiece has everything the connoisseur looks for in a typical Bosch painting: weird creatures, hellfire (no one paints burning buildings quite so well as Bosch), animals of unusual size, etc. Perhaps its most famous detail resides in the upper portion of the right panel, where a man and a woman are depicted flying through the air on the back of a giant fish, like a scene from Mikhail Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita.”

In our supposedly more enlightened age, critics tend to turn works such as this into cultural psycho-babble, instead of viewing them as a warning about the wages of sin and the temporal power of Hell. Secular analysis of Bosch brings to mind a scene in the (superb) British sitcom “Outnumbered,” in which a mother becomes concerned after her daughter draws a picture of Christ being tempted by the Devil, an event described in the Bible. The little girl even adds a somewhat Bosch-like touch to her work of a zebra observing the scene, an animal whose symbolism only the girl herself understands.

The mother opines that today most Christians do not believe people will go to a place of horrible punishments called Hell, to which her daughter responds, rather matter of factly, “Well they’re the sort of people who will be going to hell.”

Lest we forget, Bosch’s paintings were not idiosyncratic works created for his own delectation. Rather, they were commissioned by important individuals and institutions, and displayed to edify their owners and the public. In seeing so many of his works gathered into one place, one cannot help but be aware that Bosch was insistent almost to the point of mania on warning his fellow Christians that they really, really did not want to end up in Hell.

Bosch’s Place in His Artistic Tradition and Times

Perhaps because Bosch is most famous for his creepy-crawly beasties and scenes of general unpleasantness as he decries human sinfulness and folly, it is easy to forget that he came from a painterly tradition in what are today Belgium and the Netherlands that included luminaries such as Rogier van der Weyden, Jan van Eyck, and Bosch’s near-contemporary Gerard David.

These artists were famous for creating works that featured rich colors, elegant figures, and inviting landscapes. Saints were depicted dressed in robes of magnificent hues and patterns, while the angels’ wings would put all but the most exotic of tropical birds to shame. Green fields dotted with wildflowers were frequently shown through the windows of tastefully decorated homes, or alongside paths leading to the sort of pretty medieval waterside towns one would like to visit on vacation.

A great strength of The Prado exhibition, even for those already familiar with Bosch’s work, is that one comes to better appreciate him as being a part of this Netherlandish tradition. Bosch was not just a creator of monsters, but an artist whose paintings exhibit many of the same jewel-like qualities that made Flemish and Dutch painting of this period highly coveted by art collectors across Europe. By seeing virtually all of Bosch’s work collected together in one place, the visitor can step back and survey the artist’s output as a whole, and as part of this northern European tradition in painting, rather than just examining the idiosyncratic components of his art.

For example, if I were asked to guess Bosch’s favorite color, after seeing this exhibition I have to conclude the answer to that question is “Pink.” Sometimes Bosch paints a shade of pink that has the delicate newness of a lamb’s tongue, or elsewhere he might evoke the color of raw salmon, but whatever the hue, pink is on display just about everywhere you turn in this exhibition. The fact that the exhibition space itself is painted in cool grays and whites only makes the brightness of the pinks in Bosch’s paintings stand out even more.

Take one of my favorite works by Bosch in this retrospective, the quietly contemplative “St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness” (c.1504-1505). Here the outspoken forerunner of Christ is depicted, not in camel skins eating locusts and wild honey, nor standing ankle-deep in the Jordan River, but sprawled on the ground dressed in a robe the color of raspberry sherbet.

As one might expect from Bosch, the picture contains a few oddities such as the bizarre mandrake-gourd that for unknown reasons he painted over the figure of the individual who had commissioned the painting. However the verdant landscape, the saint’s languid pose, and above all the magnificent drapery demonstrate that Bosch skillfully employed some of the key hallmarks of Netherlandish art from this period, albeit in his own way.

Similarly, in the equally peaceful “Saint Christopher Carrying the Christ Child” (c. 1490-1500), the exhibition shows these Netherlandish qualities yet again. Both the saint and Jesus are dressed in pink, with the billowing folds of the former’s garment reminding one of slices of smoked ham, while the particularly elegant child wears a garment the color of roast beef.

Yes, there are bizarre things are going on the background, such as a dragon peering over the edge of a garden wall, or a dead bear hanging from a tree, but the beautiful northern landscape itself stretches far off toward the horizon, with gently rolling, wooded hills dipping their toes into the cool water.

In these and in other, quiet works in the show, Bosch manages to bring the viewer to contemplation, showing us that he is more than just the fellow who paints pictures of creepy-crawly things. Indeed, the exhibition as a whole reveals Bosch as not only a man of deep religious faith, but also one capable of enormous and varied output. Even if the more visceral images from his brush are what we remember and associate with his career, it is in his quieter paintings that Bosch reveals a bit of himself, as someone longing for the quiet assurance of divine mercy and a return to the natural order of things in a world gone mad over the deliberate pursuit of sin.

Because of its size and the fragile nature of many of the works on display, it is highly unlikely a show of this caliber on Bosch’s work will ever be mounted again. Therefore, if you are fortunate enough to be able to travel to Europe this summer, I strongly urge you to consider stopping in Madrid to see this exhibition. Even if you cannot make it, however, the sumptuously illustrated, highly informative catalogue alone is well worth adding to your library. Bosch is an artist whose work may not be as fully understood today as it was in his own lifetime, but in the sulfur-scented society in which we live now his art seems more relevant than ever.

“Bosch. The Fifth Centenary Exhibition” is on display at The Prado until September 11, 2016.