I went to the Venice Biennial with my mom in 2013. Back in New York I heard artists talking about how the biennial exhibition played out, but for me, it was a destination I’d always wished to visit. We bought our tickets to the big curated exhibition, but some of the most interesting work was on the fringes.

Tucked into store fronts and second floors, smaller exhibits made farces of global problems like climate change, third-world poverty, and religious extremism, while taking on philosophical ideas and political ideologies.

When we happened upon Rhizoma, an exhibit in association with the Edge of Arabia arts collective, we were both completely floored. My mom and I are cultured, well-educated Americans, but we had never seen work by Middle Eastern artists. During the Biennial, we also saw work from Bahrain in a beautiful, breathtaking exhibit in the main gallery spaces, but the work we saw at Rhizoma was different. It was spontaneous, unexpected, hilarious, ideologically dangerous; in short, it was border-obliterating.

Steeped as we were in American news culture that portrayed Middle Eastern and Saudi Arabian Muslims as very serious individuals concerned only with religious and family life, we were surprised to find work that spoke not to how one ought live in accordance with God’s law, or about oppressive regimes, but art that spoke first and foremost to the joy and hilarity of the human condition.

My particular favorite at Rhizoma were the films of Sarah Abu Abdallah. Of those, the one that knocked me completely out of my comfort zone then redefined it was a spoof on domesticity. In it, a woman in a chador (if memory serves) carries a large cooking pot from room to room in her house.

Standing in the living room, she raises the pot, overturned, above her head, and lowers it down onto herself, until she is entirely hidden, and the pot appears as simply an overturned pot on the floor. The kitchen, the laundry room, the bedroom, all end up with this woman concealed in the pot. Watching it, I felt that feeling that only art can give you—complete transcendence, total autonomy, that I was being intimately communicated with, and a kinship with the artist.

Rhizoma was curated by Sara Raza, a London-based critic and curator, and Ashraf Fayadh, a Saudi-raised Palestinian, poet, curator, and artist. I am forever in the debt of these two curators, who brought me closer to the Middle East than any airline could ever match.

These curators transcended all boundaries and borders between my heart and the artists they featured, between my heart and their own. The work they presented shrunk the space between us. Of the exhibit, Fayadh said, “We aim to provide a clear vision of the radical transformation in Saudi art, which is not more affiliated with its roots, to the real culture represented by the awareness of the different living conditions in Saudi Arabia.”

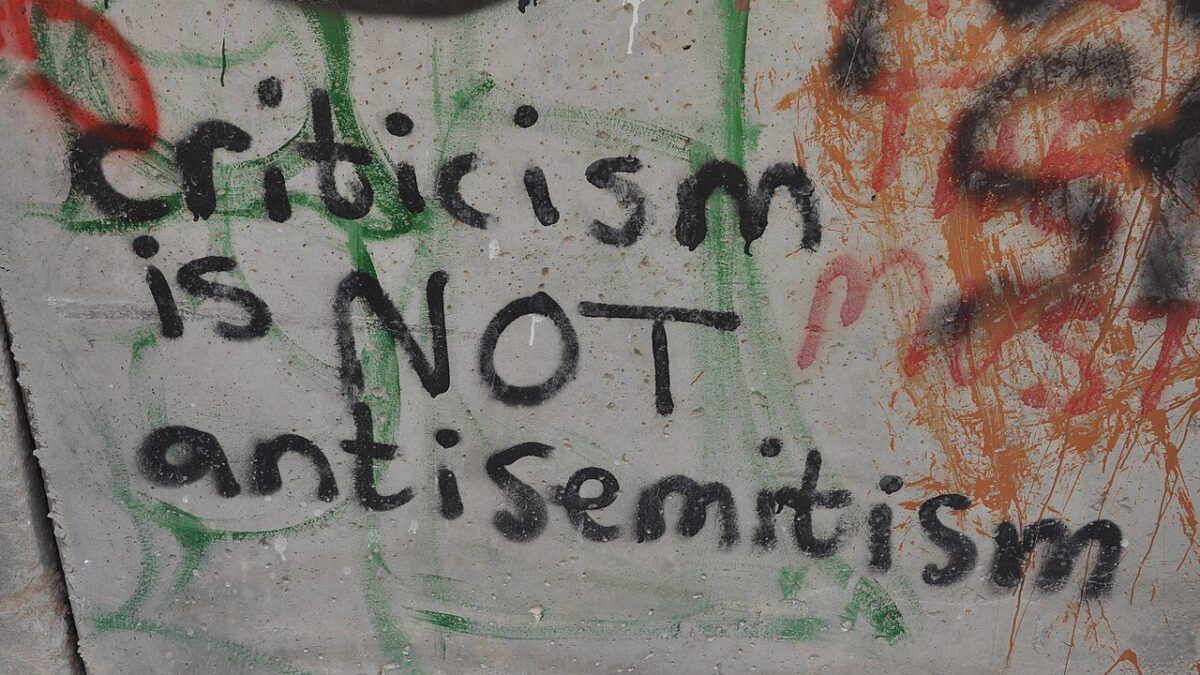

Free Speech Is Not a Crime

Saudi Arabia is preparing to execute Fayadh for apostasy, which is the renunciation of a religious or political belief. The evidence of this crime is his own poetry. He has been imprisoned in Saudi Arabia for more than 32 months, and has been denied legal representation or visitors. An online petition aims to save Fayadh’s life, and I hope it, and an outpouring of support for Fayadh from the international community, can succeed.

Artists of the West should support the kind of grassroots arts efforts Fayadh and his colleagues generate. Art can bridge the gap between us, and spread ideologies of free expression and independent thought.

The charge of apostasy is a bogus charge that really means Fayadh has been found guilty of expressing himself freely and thinking independently. Governments that fear these traits in their citizenry have long squashed artists and artistic endeavors, because they know art is vastly more powerful that all other forms of communication, more formidable than any treaty or summit.

I don’t know Fayadh, but I feel he is my brother in art. This unity, despite differences in religion, language, or place, is what his government must fear. Art is a visible target, because artists don’t hide their work but present it, share it, and talk about it. Art is an easy target because of that visibility. Governments hope to extinguish individual liberty and intellectual freedom by destroying art and its makers because in crushing art and artists, others who may speak out are cowed. Let’s not let them do it.

It doesn’t matter if Fayadh is guilty of apostasy. No intellectual mind could consider apostasy a crime under any circumstance, for the true nature of intellectual exploration is that all ideas, all perspectives, all beliefs, must be investigated to their root, and those roots are to be held up to scrutiny.

It is not enough to know what we believe, but to know why we believe it. Understanding why one feels the way one does about God, love, and communication is more important than blindly following what we are told is correct. Perhaps after having undertaken this exploration, the mind and heart will unite under one belief system, and perhaps not. But the truest cause is the one of questioning and examination.

This Also Proves American Artists Aren’t Oppressed

The idea that an artist could be imprisoned for his nonviolent poetry is completely foreign to American artists, and must be abhorrent to all free thinkers. In the United States, poets do not fear imprisonment after writing poems that renounce either the government or religion. Yet contemporary American artist activists would have us believe their right to create work is under siege by a corrupt oligarchy.

This is just not the case. We have immense freedom to say whatever we wish to say, whenever we wish to say it, to whomever is interested in listening. We can do any number of things to ourselves in the name of performance.

In 2010 a friend of mine authored a show in which she created a vagina fountain. Yes, it was a fountain that emerged from her vagina. It was pretty incredible, in all senses of the word. We can cut ourselves until we bleed, submerge the figure of Christ in a jar of urine, menstruate on stage, cover ourselves in chocolate, display homo-erotic photographs in our elitist cultural institutions, and all manner of much tamer things.

I have authored and performed in a play called “How to Sell Your Gang Rape Baby for Parts” and, amazingly, there was absolutely no governmental retribution. We can say with certainty that American artists need not fear state repercussions as a result of casting off their religious beliefs.

How can American artists continue to shout about how they’re being oppressed? Artists are not under government scrutiny and do not routinely get badgered or bullied for their beliefs or lack thereof. Passports are not confiscated, travel is not restricted, subject matter is not banned.

Why, then, do American artists cling to the belief they are oppressed? It’s because they feel that being victimized is the only way for them to achieve relevancy, the only way for their voices to be considered authentic. We live in a culture that elevates the perspective of the victim, and artists want to be noticed, so they purport to be victimized.

Let’s Get Some Perspective and Champion the Real Victim

Contemporary artists demand more support, such as the kind of government funding Scandinavian countries provide. They demand living wages on non-commercial theatre productions, and claim oppression when, to support their art work, they must work at jobs other than art-making.

No doubt, it’s hard to make art while being broke. That’s always been true. But neither art itself nor the government owes anyone a living. Artists who feel they are not being admitted to the higher echelons of artistic influence are not suffering oppression. Being left out of deciding who gets the big funding is not tyranny, but a sentence of death for a collection of poems is.

Could things be better in the United States? Could we, as a nation, in our laws and actions, be better living up to our ideals? Yes, of course, things could always be better. But the disparity between our goals and our reality is not a reason to focus on nothing else or to only advocate for bettering our own nation and citizens’ circumstances. Our brothers and sisters in art worldwide need us.

Let’s quit the navel-gazing and focus on raising our voices, our brushes, our sharpened pencils, our keyboards, our condiment-covered bodies to advocate for justice for our artistic brethren who are being victimized for the very act of making art. We really don’t have it so bad, but the Saudi government, an American ally, is planning to kill Ashraf Fayadh because of poems. Poems. Please join with me to advocate for Fayadh’s release.