It has often been noted that there are two kinds of James Bond fans: those who have read the books and those who haven’t.

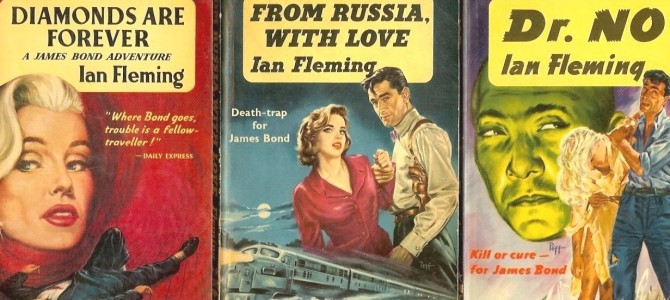

Between 1953 and 1966, the character of James Bond, agent 007 in the British Secret Service, appeared in 14 books—12 novels and two short story collections—written by Ian Fleming. However, Fleming died in 1964, and the last two books were published posthumously. In spite of Fleming’s death, the success of the cinema Bond continued to create more demand for the literary incarnation.

A few years after the last of Fleming’s Bond books appeared, James Bond was given new life by Glidrose Publications, now Ian Fleming Publications Ltd., which holds the copyright to the James Bond publishing franchise. For better or worse, the latest installment is Trigger Mortis: A James Bond Novel by Anthony Horowitz (310 pp. Harper/HarperCollins Publishers; $27.99). This is the 36th official post-Fleming James Bond story, and Horowitz is the eighth author to continue the series.

With the hoopla surrounding the latest Bond film, Spectre, freshly upon us (released in theaters today), the timing of Trigger Mortis seems most propitious. Besides both continuing their respective Bond franchises, however, Trigger Mortis and Spectre are unrelated. Ian Fleming Publications Ltd. has nothing to do with the films, which are made by Eon Productions Ltd. Spectre is the twenty-sixth James Bond film to date, though only the 24th from the Eon franchise, the 1967 parody Casino Royale and 1983’s Never Say Never Again being exceptions.

With any luck, the new flick will drive fans to consider the Bond books. The synergy here is perhaps best thought of as a variation on Ian Fleming’s adage that “nothing propinks like propinquity,” which first appeared in chapter 21 of Diamonds are Forever, published in 1956, and later made famous by U.N. Ambassador George Ball.

James Bond Lives

Trigger Mortis is what is known as an official “continuation” novel. This is to say, it is a novel written by a new author, commissioned by the estate of the deceased author, to keep the literary brand alive. Presumably also to keep the cash cow’s milk flowing. In this, Anthony Horowitz is apparently an old hand, having written two internationally bestselling “official” Sherlock Holmes continuation novels, House of Silk in 2011 and its sequel called Moriarty in 2014. (Horowitz might be best known as the creator of the British TV show Foyle’s War, which has gained something of an American following on PBS and Netflix.)

Prior to Horowitz, Bond’s post-Fleming existence was first given life by Kingsley Amis, the celebrated author and Fleming pal. This first effort, Colonel Sun (1968), was authorized by Glidrose Publications, and written by Amis under the pseudonym Robert Markham. Yet, Ann Fleming, Ian’s wife, was furious at this development. “Though I do not admire ‘Bond’,” she wrote to her friend Evelyn Waugh, “he was Ian’s creation and should not be commercialized to this extent.” She wrote an excoriating review for the London Sunday Telegraph, but fear of libel halted its publication. In 1973, Glidrose authorized Ian’s biographer, John Pearson, to write the fictional, James Bond: The Authorized Biography of 007.

Not connected to Glidrose/Ian Fleming Publications, Eon Productions commissioned two film novelizations, James Bond, The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and James Bond and Moonraker (1979), both written by the late Christopher Wood. He was also scriptwriter for both films. The stories as filmed had almost nothing to do with the Fleming stories of the same name (especially The Spy Who Loved Me), so Eon had them turned into novels. Both are actually really enjoyable reads.

No additional Bond stories were published however until 1981, after Ann Fleming died. The series was entrusted to novelist John Gardner who updated the setting to the 1980s. Gardner wrote 14 Bond novels and two film novelizations. Once his health failed, the mantle was passed to an American author, Raymond Benson, who penned six contemporary Bond novels, three film novelizations, and three short stories. Six years later, Sebastian Faulks was commissioned to write Devil May Care (2008), set in 1967. This was followed by Jeffrey Deaver’s Carte Blanche (2011), which once again chose a contemporary setting, and more or less ditched the Bond persona in all but name. Then William Boyd delivered Solo (2013) which continued Bond in the late 1960’s era.

These efforts all have their own charms, strengths and weaknesses, but with the exception, perhaps of Amis’ Colonel Sun, and Wood’s two film novelizations, none really merit repeat reading.

Trigger Mortis, by contrast, is set in 1957, just a couple of weeks after the events depicted in Fleming’s Goldfinger (1959). Horowitz’s task, therefore, isn’t merely to pull off a fresh Bond novel that remains essentially faithful to Ian Fleming—which is difficult enough, but also to ensure that it makes sense within the literary firmament of Fleming’s James Bond.

Horowitz apparently had a leg-up on this, supplied by the Fleming estate. As the cover of Trigger Mortis notes, it was written “with original material by Ian Fleming.”

This “original, unseen” Fleming material amounts to an unmade television treatment by Ian Fleming titled “Murder on Wheels,” about 007 taking part in a Formula One race to foil a Russian plot to kill a British racecar driver at the Nürburgring race track thereby ensuring a victory in the name of Soviet superiority. Horowitz writes in his acknowledgements that this material was a rough treatment with an additional bonus of little more than “four or five hundred words” of usable Fleming description and dialogue.

Horowitz said in the book’s press release: “I was so glad that I was allowed to set the book two weeks after my favourite Bond novel, Goldfinger, and I’m delighted that Pussy Galore is back! It was great fun revisiting the most famous Bond Girl of all… My aim was to make this the most authentic James Bond novel anyone could have written.”

What constitutes, one wonders, “the most authentic James Bond novel”?

Ian Fleming’s Accomplishment

The James Bond novels have sold more than 100 million copies since their first introduction 62 years ago. The books first really took off when, in March 1961, President John F. Kennedy named Fleming’s From Russia with Love (1957) as one of his ten favorite books in Life magazine. The 1962 release of the film Dr. No by Eon Productions pushed that star even higher. Though Fleming passed away before witnessing the next ascension, the release of Eon’s film adaptation of Goldfinger in 1964 created an international Bond mania. Ever since, Fleming’s books and the James Bond films have generated and sustained fans across the globe.

Opinions remain divided amongst critics, however, as to the actual literary merits of Ian Fleming’s 14 books, even within the genre. Many critics find Bond to be adolescent, snobby, and violent bordering on sadistic. Yet, Fleming has also had plenty of respectable defenders, then and since.

Fleming’s critics, however, can be safely ignored. His work holds up remarkably well. The original Bond books remain effortlessly absorbing, wonderfully diverting, and richly rewarding. One can just about randomly grab a Fleming Bond book, turn to any old page and become very quickly drawn in. Even if you concede Fleming was not without occasional lapses into bad writing, such episodes zip by without causing any real harm.

Fleming offers stories that are at once hardnosed and fantastical. There is driving narrative, sharp action, and lucid, occasionally lyrical, prose. And perhaps most memorably, there is Fleming’s impeccable, yet idiosyncratic, attention to the small details that helps create a sense of verisimilitude and authenticity. Even when the same silly villainous excesses associated with the films appear in the novels, the setting has made them seem plausible.

Kingsley Amis admiringly dubbed this “the Fleming effect,” and explains it as “the imaginative use of information, whereby the pervading fantastic nature of Bond’s world, as well as the temporary, local, fantastic elements in the story, are bolted down in some sort of reality, or at least counter-balanced.” As Umberto Eco explains, Fleming “takes time to convey the familiar with photographic accuracy” so that the reader’s “credulity is solicited, blandished, directed to the region of possible and desirable things.” This, in turn, enables Fleming to pull off his sleight of hand: “for the rest, so far as the unlikely is concerned, a few pages suffice and an implicit wink of the eye.”

Playboy magazine offered an intelligent homage by way of introduction to their interview of Fleming, published in December 1964, four months after his passing:

Despite, or perhaps in part because of, his enormous popularity, the literary establishment took little notice of Fleming during his lifetime, and not much more at his death. In general, their judgement of his worth may prove to have been deficient, for he may still be read when novelists presently of some stature have been forgotten. He had an original view; he was an innovator. His central device, the wildly improbable story set against a meticulously detailed and somehow believable background, was vastly entertaining; and his redoubtable, implacable, indestructible protagonist, though some thought him strangely flat in character, may well be not so much the child of this century as of the next.

What’s more, despite the now otherworldly nature of our immediate past, Fleming’s books are not quite as dated as one might expect. While clearly of their period, Fleming’s creation is not without some foresight. As the late Christopher Hitchens wrote in his introduction to the Penguin edition of one of the Bond books: “The staying power of the books… is… partly and paradoxically attributable to their departure from standard Cold War imagery…By some latent intuition, Fleming was able to peer beyond the Cold War limitations of mere spy fiction and to anticipate the emerging milieu of the Colombian cartels, Osama bin Laden and, indeed, the Russian Mafia, as well as the nightmarish idea that some such fanatical freelance megalomaniac would eventually collar some weapons-grade plutonium.”

Anthony Horowitz’s Trigger Mortis has, it would seem, a rather heavy burden to carry.

Trigger Mortis or Rigor Mortis?

In Trigger Mortis, Horowitz begins with Bond suddenly enmeshed in a new and not altogether happy domestic relationship with Pussy Galore, the lesbian criminal turned Bond ally and lover. As he contemplates pushing her out, M sends him on a mission to the Nürburgring race track in Germany to protect a British driver from a potential Soviet assassination plot. In preparation, Bond improves his racing skills under the tutelage of Miss Logan Fairfax, the racing-devoted daughter of a famous driver. Pussy reappears, being chased by two would-be assassins who very nearly kill her, though Bond intercedes with Logan’s help just in the nick of time. Pussy and Logan meet, and Pussy decides to leave Bond for Logan.

Bond continues to Nürburgring and during the race succeeds in saving the British driver, nearly killing the Soviet assassin. While there his interest is peaked by the appearance amongst the Soviet camp of Korean-American millionaire Sin Jai-Seong, known as Jason Sin. Bond infiltrates Sin’s castle in Germany, barely escaping with photographic evidence suggesting some possible connection between Sin, the Soviets, and the American Vanguard rocket program; he also escapes with an American, Ms. Jeopardy Lane, who was posing as a journalist but is later revealed to be a U.S. Secret Service Agent investigating Sin’s possible involvement with counterfeiting.

Bond follows the lead to the United States, and finds himself—spoiler alert!—up against the Soviet backed Sin’s evil plot to fell the Empire State building and destroy part of NY, and also undermine America’s space program, which is set-up to take the blame for the forthcoming conflagration. Sin’s hatred of all things American is rooted in his survival of the No Gun Ri incident, in which U.S. forces killed possibly hundreds of innocent civilians during the Korean War, including his family. With Jeopardy’s help, Bond not only survives multiple attempts on his life, but foils Sin and saves the day. Jeopardy agrees to an assignation with Bond, but on her terms, with no strings attached.

It is evident at the outset of Trigger Mortis that Horowitz is a Bond fan, and that he has mined Fleming’s oeuvre to populate his narrative with familiar Bond tropes. The effect, alas, is more of hack pastiche, than successful recrudescence.

Too Much, All At Once

He is not the first Bond continuation novelist to try and unnaturally smuggle into one novel all the little familiar tidbits of Bond’s inner life in the British Secret Service. But it doesn’t work. Fleming offered such minutia in dribs and drabs across 14 books. By somewhat breathlessly squeezing as much of this as he can in, Horowitz has, at best, conveyed a bird’s-eye view of floating caps of ice, missing entirely the vast icebergs underneath. The effect is more static and stilted than vibrant and natural. A small but telling example from page 35, referencing how Bond’s secretary, Miss Loelia Ponsonby, stays informed of goings-on:

Perhaps she had picked it up on the powder-vine, the illegal conduit for information that began in the girls’ restroom.

Now compare this to Fleming’s treatment in Moonraker (1955), the only time that the “powder-vine” is ever mentioned:

Well, he’d just have to wait for news from the only leak in the building – the girls’ rest-room, known to the impotent fury of the Security staff as “The powder-vine.”

The difference here is subtle, but striking. With wonderful economy, Fleming conjures up vast inner workings of the Secret Service. Horowitz, by contrast, conveys a simple fact. This is not itself debilitating, to be sure, but the accumulated effect is perceptibly diminishing.

Far more troubling is Horowitz’s apparent desire to smuggle the 21st century into the novel. It appears Horowitz intends to remediate, or at least remonstrate, Bond’s perceived sexism and homophobia, as well as cast a mildly critical, disapproving eye on his unenlightened habit of smoking.

James Bond is a 60 cigarette a day smoker, so Horowitz “subtly” adds some anti-smoking messages to Trigger Mortis. Early on it’s a news item about the link between smoking cigarettes and cancer on the front page of The Times—this, incidentally, is another anomaly as The Times back then did not feature news on its front page. Much later, at a crucial juncture, as Bond is rushing madly to save the day he hits a temporary endurance limit: “…he stood there, hunched over and gasping for breath (all those cigarettes – he was feeling them now)…” (Page 262).

Horowitz seems entirely oblivious to the violence this literary tick does to whatever sense of Fleming-like authenticity he musters. The situation only worsens as Horowitz turns to Bond’s attitudes towards women and homosexuals. In this, Horowitz’s desire to revisit Pussy Galore does him no favors.

Knocking Bond Down A Peg

In interviews, Horowitz says part of his interest in Pussy Galore was to see what became of the character: “The novel Goldfinger finishes with a Stratocruiser crashing with Bond and Pussy Galore on board. We don’t really know what happens after that. … So I thought, ‘Why doesn’t he bring her home with him?’ Then it gave me something to write about: Bond living with a girl and trying to be domestic, which is hopeless…’”

Where to begin? First, Fleming actually suggested Pussy’s fate in Goldfinger when, after they’ve been rescued, she playfully asks Bond: “Will you write to me in Sing Sing?” Second, to essentially rescue her from U.S. custody and bring her back to Bond’s home in the U.K., involves a tremendous fudging of the internal logic of Bond’s world, which Horowitz rather lamely and implausibly shrugs off with, “Bond felt he had no alternative… justifying his actions by reporting (falsely) that she had agreed to co-operate and might have information that could help.” He then has to further paper over this implausibility with tin-eared dialogue about cleaning up his mess, and possible CIA operatives eager to take Pussy into custody. It quickly becomes clear that one of the great benefits to Horowitz of this scenario, perhaps even its raison d’être, was to be able to develop a strong female character with which Bond may be lightly taunted and challenged, and eventually knocked down a peg.

In Fleming’s Goldfinger , Pussy, despite being a strong and intelligent criminal character, as well as a lesbian, is turned into an ally and then lover by Bond. As Fleming economically rendered it: “He said, ‘They told me you only liked women.’ She said, ‘I never met a man before.’” It was arguably Fleming at his least effective and most flippant, but it was essentially a throw-away bit at the end of the novel. Yet Horowitz won’t let it go, seemingly eager to put the universe right for Pussy Galore.

As he noted in a publicity interview with NPR: “to suggest for a minute that Pussy Galore was a sort of a gay woman who could somehow … be cured by her first relationship with a heterosexual man would, I think, be deeply, deeply offensive today. And of course it’s not something which I consider to be even remotely true at all. And so in the book, in dealing with her, I had to take that on board and very carefully referenced her upbringing, but then gave the whole story a twist that I think gives it almost, dare I say it, a feminist edge — certainly a modern one. … [Not only] is she a strong character, but at the end of the day she is a very independent character. And without wishing to give away too much of the story, you know, what she does to Bond — the way she reacts to him and the way their relationship develops and even ends — is, I think, a learning curve for him.” In another interview, Horowitz adds: “I wanted [Bond] to have a slight comeuppance… to find a way to chide him.”

Thus Pussy Galore is depicted first as idly teasing with, “But you’re different, right? Saving the country three times before lunch…” (Page 20), and then later, slightly less playfully, “I got by perfectly well without you and don’t think I need you now” (page 21). Horowitz even has Bond musing how he “certainly resented the slight mocking tone” (page 23). Later, Horowitz has Bond fail to protect Pussy from being attacked and very nearly killed (rather ridiculously and unoriginally, the weapon of choice is gold paint to suffocate her skin). As she lays recovering in the hospital, Horowitz has her lower the boom on Jimbo: “Well, whaddya know…for once, Mr. James Wonderful Bond got it wrong…”(page 65).

Finally vindicated, Horowitz writes off Pussy’s part of the story by having her dump Bond and run off with Logan Fairfax, the second strong female character of the book. “That is a double whammy for an old-fashioned macho man like Bond,” Horowitz says in one of his publicity interviews.

Just as an aside, the gold paint shtick simply doesn’t work the way Horowitz intends. First off, it is an instance where Fleming got it wrong in the original, as breathing is done through the mouth and nose, not the skin, so no amount of paint on the skin will lead to asphyxiation. Further, it was related very clearly in Goldfinger as the personal sadistic sexual perversion of Goldfinger himself. It simply makes no sense for the unidentified would-be assassins to choose this method of killing Pussy. Especially after Goldfinger’s entire criminal and commercial empire was already ended. Likely it is for this reason that Horowitz doesn’t bother to explain who, exactly, is seeking revenge on Pussy because, well, he can’t without inventing additional parts of the Goldfinger story.

Bond, Feminist Bond

By now this pattern should be clear regarding the women Horowitz brings into Bond’s life in Trigger Mortis. In yet another interview, Horowitz notes that Trigger Mortis is “true to the character and keeps him [Bond] as fans would want him…But then it always challenges and nudges and says ‘well wait a minute’… With women, he has this sort of patronising carnal attitude with them… But then by creating very strong women he is given quite a run for his money and his attitudes are challenged.”

Horowitz had to put more flesh on the bones of Jeopardy Lane, but only a little. Horowitz is unbothered by the fact that, in 1957, the only women in the U.S. Secret Service were secretaries. But no matter, a love-interest Bond girl was needed.

“Jeopardy is at least as effective a spy as James Bond and probably more so,” Horowitz explains in another of his publicity interviews. “Without her, he would be killed. He has to acknowledge that she is unstoppable and doesn’t make mistakes, while he does.” Sure enough, after she first saves his life by rescuing him from a somewhat silly, cinematic quality gun battle, Horowitz notes: “Bond had already come to the conclusion that he was going to have to tell her everything. Jeopardy had just saved his life and now she was taking over the whole operation and being utterly businesslike and unapologetic with it. She was impressive in every way and even though it was half past four in the morning, he had a sudden impulse to grab her by the neck and to kiss those serious lips of hers so hard they bled” (page 189-190).

Poor, star-struck Jimmy. Despite additional “impressive in every way” type lines, Horowitz fails to actually demonstrate Ms. Lane’s near-perfection. To be sure, Horowitz still has Bond retain his hero’s mantle, still saves the day, and still beds the girl, but only with the Bond girl’s superiority fully acknowledged.

This is all, to put it very mildly, utterly out of sync with Ian Fleming, and Horowitz’s claim to authenticity in continuing James Bond is fairly absurd.

Horowitz’s efforts call to mind Roger Moore’s anecdote about one of his “intelligent, tough, independent beauty” leading ladies. Moore, who played Bond in seven films, tells of one occasion when director Lewis Gilbert is giving direction to the leading lady. “‘You come in here, and follow him over there,’ says Gilbert. ‘Why do I always have to follow him?’ she asked. ‘Because, dear, he is f–king James Bond!’ Lewis helpfully replied.”

(As an aside, Moore doesn’t identify the actress in question, but my Bond fan-geek instincts suggest it is Lois Chiles who played Dr. Holly Goodhead in 1979’s Moonraker. Chiles took her role so seriously that Moore took to calling her “Sarah Bernhardt Chiles” on set.)

More Anomalous Assaults

Another especially egregious 21st century anomalous assault by Horowitz is found in chapter 12. Horowitz risibly and jarringly introduces the character of Charles Henry Duggan, head of Secret Service “Station G” in Germany. (In Fleming’s world there is a Station B, in Berlin, which would seem to serve the same function, described lazily by Horowitz as, “intelligence gathering, particularly with reference to Eastern Europe.”) Here is Horowitz’s introduction:

Duggan was a great many things that are unusual in the world of the secret service. He was fat – really fat – loud, bearded, frequently indiscreet and often, at least in appearance, drunk…He was also homosexual and didn’t care if people knew it. He and Bond had almost come to blows late one night in a Montmartre bar on the only occasion when the topic had come up, Duggan damning him for his Protestant upbringing and his blinkered world view. “The trouble with you, James, is you’re basically a prude… Change the law and let people be what they want to be – that’s what I say. And as for you, maybe you should try to be a bit less of a dinosaur. This is 1957, not the Middle Ages! The second half of the twentieth century!” (Page 145-6).

Ah, but lest we wonder why Bond would allow an openly homosexual agent (officially barred from such government service until the 1990s) to brow-beat him in this way in 1957, Horowitz helpfully adds: “but the two of them had served together… during the war and had even shared a flat for a short while in Victoria”—so that’s alright then.

Though clearly a bother to Horowitz, just by way of correction, here is Fleming’s rendition of Bond’s attitudes in this regard from Goldfinger:

Bond came to the conclusion that Tilly Masterton was one of those girls whose hormones had got mixed up. He knew the type well and thought they and their male counterparts were a direct consequence of giving votes to women and “sex equality”. As a result of fifty years of emancipation, feminine qualities were dying out or being transferred to the males. Pansies of both sexes were everywhere, not yet completely homosexual, but confused, not knowing what they were. The result was a herd of unhappy sexual misfits–barren and full of frustrations, the women wanting to dominate and the men to be nannied. He was sorry for them, but he had no time for them.”

Horowitz also allows a 21st century anti-American military cynicism to creep in. Not just in the overlong and labored background on No Gun Ri, which is at least partly forgivable for being delivered by the evil Jason Sin, but also in the incredibly—indeed, implausibly—silly reception Bond receives at the Naval Research Laboratory on Wallops Island. This was Bond’s first stop upon returning to the U.S., there to warn the Navy Liaison and Project Officer, Captain Eugene T. Lawrence, about possible Soviet sabotage of the upcoming Vanguard rocket launch. On the heels of Bond’s triumph in Goldfinger—where Bond was fêted in Washington “treading the thickest, richest red carpet… a big brass lunch at the Pentagon, an embarrassing quarter of an hour with the President” and an offer of the American Medal of Merit [muted by M]—it seems incredible that he would be so easily dismissed. As Horowitz has Captain Lawrence say during the official interview, straight faced, “In a court of law I’d say it was your word against theirs.”

Although entirely unkind to point out, I can’t help but note that Horowitz places Bond “behind the wheel of his 4½ litre Bentley” on page 22, before later correctly pointing out on page 39 that Bond “had bought the Bentley Mark VI just days after he had lost his old model” [the “4½ litre”] in Moonraker—four novels earlier. So much for the most elementary “continuation” novel precision.

He Leaves No Heirs

Not that Trigger Mortis is all bad. Stripped of the many anomalous assaults on Bond’s world, it would be a very workman-like, hack pastiche. Some of the set-pieces are pretty good, too. The Fleming car-race set piece is rather good, and would actually have been better as a stand-alone short story. Horowitz’s prologue, which Bond doesn’t appear in, is also a good bit of writing, both engaging and evocative. Had it not been “a James Bond novel” set within the timeline of Ian Fleming’s creation, but merely a pulp espionage thriller, it’d be a far less frustrating experience. Trigger Mortis has its moments, to be sure, but even at its best it isn’t nearly as good as Ian Fleming at his worst.

When all is said and done, it’s hard not to agree with Kingsley Amis’s admiring and intelligent study The James Bond Dossier (1965), which he concludes with: “Ian Fleming has set his stamp on the story of action and intrigue, bringing it a sense of our time, a power and a flair that will win him readers when all the protests about his supposed deficiencies have been forgotten. He leaves no heirs.”

Which is to say that in the end Trigger Mortis, like most of the post-Fleming James Bond books before it—and even the films in this context, may or may not successfully expand the world of James Bond, but they most assuredly cannot really harm it.