While my fellow American Catholics await their moment with Pope Francis, my own family already had ours, back in February while we lived temporarily in Rome. We arrived before dawn for the Wednesday papal audience to claim one of the cherished spots along the white barricades in St. Peter’s Square that mark the Popemobile route.

Still, we didn’t hope for much more than a good photo opportunity. Our young daughters clutched prayer requests and artwork “to give to Pope Francis,” but we did our best to lower their expectations, since the word on the street was that he only stopped for babies. Finally, we saw him ‘round the corner nearest us, smiling, waving, and, yep, kissing a baby.

Then, all of sudden, the pope was looking, pointing, and smiling, right at us. Or, to be more specific, right at my two little girls. Before I had time to take it in, he gestured to his attendants, who ran over and grabbed those notes “he’ll probably never get” to put them into the hands of the Holy Father. Then he moved on, while my husband and I looked at each other, thinking, “Wait. Did that just happen?” (It did. I have the pictures.)

It was a pinch-me moment that left us walking on air for a day or so. But it was also a personal moment of reckoning. Not too long ago, I was not the kind of woman who would have gone all swoony at an encounter with the pope. I wasn’t even Catholic. And not just “not Catholic”: I was the one wearing the clerical robes and preaching the sermons—because I was an ordained Protestant minister.

Religion Empowers Me

Ten years ago, after a long journey and some serious wrestling with God, I found myself relinquishing my ordination credentials and receiving the sacraments of initiation in the Catholic Church. Naturally, many people in my life were surprised and confused, a confusion that I completely understood. When a friend changes her mind about a weighty matter, be it political, moral, or religious, it can be unsettling.

In my case, the confusion was magnified, because my story ran directly counter to a well-established cultural narrative: traditional religion restricts women’s freedom. Women who seek fulfillment and empowerment don’t join these traditions; they break away from them, either shedding their faith altogether or reconfiguring it in a more “progressive” form.

So when I tell people that I became Catholic because I believe the Catholic faith to be true, and that the truth really does set you free—well, it’s not so much that they disagree as that my words don’t even compute.

The Incredible Disappearing Religious Woman

Perhaps that is why, when the battle lines are drawn in our culture wars, women like me tend to disappear—at least, as women. We are hidden away in terms like “social conservatives” or “anti-abortion activists,” whose agendas are inevitably pitted against the goals of “feminists” or “women’s organizations.” The needs and rights of women are all on one side, the religious zealots’ all on the other.

Take one recent example that prominently featured my own faith community: the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) mandates that all but a narrowly defined group of “religious employers” provide both contraceptive and abortifacient drugs to their employees. The Catholic Church and other religious groups, not surprisingly, viewed this as an attack on religious freedom. Planned Parenthood and the National Organization for women, not surprisingly, lauded the policy as an advance for women’s rights.

The story almost writes itself, doesn’t it? “Religious Liberty Versus Women’s Health: Catholic Bishops Square off Against Feminists.” But here’s the problem. There was no “women’s position” on this issue. Gallup polling at the time showed women almost evenly divided, with slightly more support for the religious leaders who opposed the mandates. And women’s opinions mirrored those of men almost exactly.

Mandatory contraception coverage was no doubt a major agenda item for groups like Planned Parenthood, who claim to represent women’s interests. Sandra Fluke notwithstanding, however, the majority of women did not see free contraceptives as an issue on which their full liberation hinged. On the other hand, many women did recognize a threat to their liberty in the HHS conflict—not to their rights as women, but as people of faith.

Yet none of that reality broke through, because the story was that religious freedom and women’s rights are a zero-sum game. If those male Catholic bishops get what they want, women lose.

Religious Freedom: Not Just for White Guys!

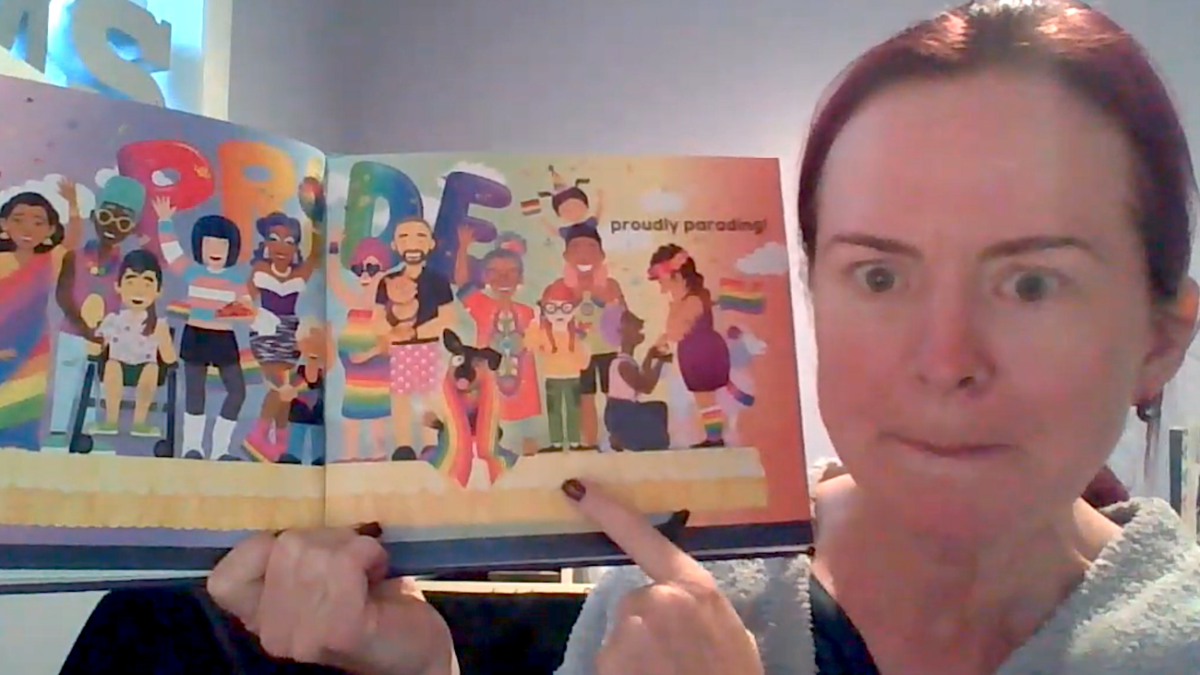

Since the HHS battle first began, the issue of religious freedom has become even more politically fraught, and unfortunately, its framing has gotten even less nuanced and more adorned with scare quotes. “Religious freedom” means women can’t get the Pill. “Religious freedom” means gays and lesbians can’t get a wedding cake. “Religious freedom” means robed men—whether judges or priests—get to tell women what to do with their bodies. In short, claims of religious conscience are nothing more than a cloaking device for the oppression of vulnerable minorities, just as in the days of slavery and Jim Crow.

But this is where identity politics mask reality rather than revealing it. There are women, blacks, and, yes, even gays and lesbians who find their deepest identity not as women or blacks or homosexuals, but as Catholics, Pentecostals, Muslims, and Orthodox Jews. We are not oppressed, brainwashed, or deluded. We are rational beings who have chosen to seek truth and meaning within enduring religious traditions, over against the various forms of liberation contemporary culture promises.

Above all—and this is what people most often misunderstand—we are not traditional Catholics or conservative Evangelicals or Orthodox Jews in spite of our gender or race or sexuality. Rather, our faith gives us a framework by which to understand and appreciate those aspects of our humanity and, most importantly, to integrate them into our whole personhood.

Being Catholic has given me far more joy and empowerment in my womanhood than any women’s studies class ever did. In fact, one of the gifts of faith in the postmodern world is sweet liberation from the ruthless Procrustean beds of endlessly multiplying and ever-narrowing identity groups.

This is why, in the ongoing battles between the sexual revolution and religious liberty, those identity politics are going to get a little tricky. Are the Little Sisters of the Poor waging a war on women because they are women who don’t want to buy the morning-after pill? What about the black churches, whose members overwhelmingly oppose same-sex marriage? Are they the new face of bigotry? How about the gay evangelical who wants to seek counseling based in his religious beliefs? Does he have the right to choose how to live his life, too? Or do women’s rights, minority rights, gay rights only count when they align with progressive politics?

When Pope Francis comes to America, he will stand in Independence Hall and speak about religious freedom. No doubt he will echo the themes of his first apostolic exhortation, “Evangelii Gaudium,” which declared that “no one can demand that religion should be relegated to the inner sanctum of personal life, without influence on societal and national life… without a right to offer an opinion on events affecting society.”

When he does so, he will not be asking for a special megaphone for white men in clericals, but rather reminding Americans of a fundamental right of all people—including a lot of poor, female, black, Latino, and gay people—to bring their full humanity to the public square and contend there for the future of their country.