Samuel Gregg

Given that I’ve already written elsewhere about the lamentable understanding of economics, and free markets more specifically, that permeates “Laudato Si,” I’d like to underscore another problem with the encyclical. This concerns the sheer overreach that plagues the text.

Neither the pope nor the teaching authority he exercises is required to comment on every imaginable subject discussed in the public square, whether it is air-conditioning’s environmental impact, contemporary threats to plankton, the effect of synthetic agrotoxins on birds, or how dams affect animal migration (and, yes, all four are discussed in “Laudato Si”). The same goes for Catholic bishops. They’re under no obligation as bishops to articulate an opinion—let alone formal teachings—on every conceivable public policy issue.

One reason for this is that the Catholic Church itself teaches there is considerable room for legitimate disagreement among Catholics about the vast majority of political and economic questions (the legal treatment of matters like abortion and euthanasia being two of the better-known notable exceptions). But a second reason is that the primary responsibility for addressing most social, economic, and political matters belongs, as affirmed by Vatican II in its decree on the laity “Apostolicam Actuositatem,” to lay Catholics: not popes, bishops, priests, or members of religious orders.

Catholic clergy are perfectly entitled to hold and express their personal opinions about, say, air-conditioning, dams, plankton, or synthetic agrotoxins. When, however, an encyclical like “Laudato Si”—or formal statements issued by a Catholic bishop or Catholic bishops’ conferences—enters into discussion of the details of such topics, they seriously risk crowding out the laity from their proper sphere, or even subtly pressuring lay Catholics into adopting positions they have no obligation as Catholics to hold.

“Laudato Si,” unfortunately, does nothing to correct this tendency and, if anything, reinforces it.

Samuel Gregg is research director at the Acton Institute.

Nicholas G. Hahn III

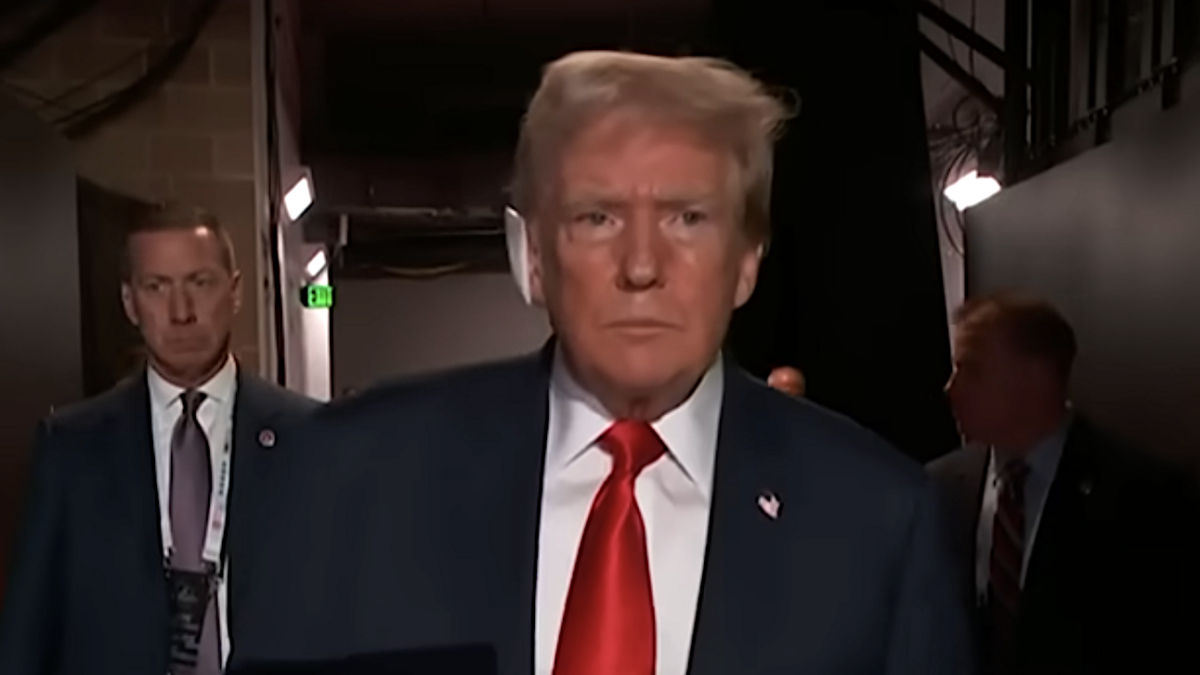

Jeb Bush has been a Catholic for 25 years and says he tries to follow the teachings of the Church. But as for Pope Francis’s recently released encyclical on the environment, Mr. Bush won’t be following any specific policy advice: “Religion ought to be about making us better as people,” Mr. Bush said during his first campaign stop Tuesday, “and less about things that end up getting in the political realm.”

Those who would try to label Mr. Bush a heretic might want to have another look at the pope’s letter.

“On many concrete questions,” Pope Francis writes in “Laudato Si,” “the Church has no reason to offer a definitive opinion.” He admits that “a variety of proposals [are] possible,” and later stresses again that “the Church does not presume to settle scientific questions or to replace politics.”

Despite the pontiff’s best intentions to steer clear of politics, his encyclical too often engages in sophisticated science and partisan policymaking. And Francis nonetheless encourages politicians to develop policies “so that, in the next few years, the emission of carbon dioxide and other highly polluting gases can be drastically reduced.”

Perhaps the encyclical‘s most troubling sections aren’t especially found in the Holy Father’s imprudent policy prescriptions, but where he seems to lay most of the blame for climate change on advances in industry and technology. Francis blames markets and advances in technology without at least admitting that the Industrial Revolution lifted more people out of poverty than ever before.

There are some unfortunate instances in Laudato Si where the pope seems to be resigning the poor to their poverty, if it means saving the environment. “The notion of the quality of life [cannot] be imposed from without,” Francis writes, “for quality of life must be understood within the world of symbols and customs proper to each human group.” Before an industrial project in a rural area that might give the third-world poor access to electricity, for example, Francis says that it must first “demonstrate that the proposed activity will not cause serious harm to the environment or to those who inhabit it.” The poor have no time for those who might romanticize their “customs” as anything other than a poverty out of which they deserve to rise.

The problem with pretending to be a scientist or a policymaker is that it dilutes the authority of the Catholic Church on issues of faith and morals. It can also sometimes lend itself to climate alarmism or peculiar advice. Like when Pope Francis worries that the polar ice caps are melting and says doomsday predictions aren’t so far off. Or when he decries the use of air-conditioning, and calls it an “act of love” to wear a sweater or turn off unnecessary lights. These silly sidebars probably shouldn’t have found their way into an authoritative document of the church. Good Catholics can disagree on how to combat climate change and shouldn’t worry about being sent to the confessional if they drive a SUV.

Francis does have some inconvenient truth for those who seek to sprinkle the Sierra Club in the name of the Most Holy Trinity. The pope forcefully rejects population control and abortion. He laments that “when some ecological movements defend the integrity of the environment … they sometimes fail to apply those same principles to human life.” Francis is clear in his critique of those who “combat trafficking in endangered species while remaining completely indifferent to human trafficking, unconcerned about the poor, or undertaking to destroy another human being deemed unwanted.

Which brings us to the pontiff’s most welcome contribution to the climate debate: Human beings are at the center of creation. “Our relationship with the environment can never be isolated from our relationship with others and with God.” Anything else, Francis writes, is just “romantic individualism dressed up in ecological garb.”

“Nature cannot be regarded as something separate from ourselves,” Francis argues. “We are part of nature, included in it and thus in constant interaction with it.” We are called to ” ‘till and keep’ the garden of the world,” Francis writes. “Disregard for the duty to cultivate and maintain a proper relationship with my neighbor, for whose care and custody I am responsible, ruins my relationship with my own self, with others, with God and with the earth.”

Nicholas G. Hahn III is the editor of RealClearReligion.

Rachel Lu

The danger of the encyclical is obvious: people will get hung up on specific environmental recommendations (of which there are several), and too much argument on those points could open some fissures among conservatives, which in turn might alienate Catholics. That’s a shame, especially at a time when Catholics have been fleeing the Democratic party in ever-greater numbers. Obviously, the left would be happy to exploit the opportunity by portraying Laudato Si as a lengthy diatribe against “climate skeptics”, which it really isn’t at all. Fortunately, Catholics from across the political spectrum seem mostly to be handling the new encyclical well, so I don’t think we’re on the brink of another Mater et Magister sort of moment.

The encyclical itself has some very beautiful passages about the natural world, but even beyond that, there is much in it for conservatives to admire. If it’s a diatribe against anyone, the target is not climate skeptics so much as modern progressives. Pope Francis is calling our attention to the way in which modernity, with its relentlessly utilitarian drive, has caused us to lose sight of the real purpose and value of fundamental goods, which include not only the natural world but also family, community and human life itself. Francis very explicitly extends his analysis to progressive initiatives like population control, which is an even graver violation of that same natural law that should motivate us to protect the environment. So even if his specific economic and environmental recommendations irritate some conservatives, it would be worth it if liberal progressives would actually read this whole argument.

Rachel Lu is a senior contributor to The Federalist.

David Marcus

What I liked: “…science and religion, with their distinctive approaches to understanding reality, can enter into an intense dialogue fruitful for both.”

This is an essential point that I thought the Holy Father addressed in a compelling way throughout the encyclical. Climate change, regardless of how anthropomorphic or catastrophic one believes it to be, is a moral issue. Science itself must be silent as to whether changes in the environment are good or bad. It was right for the pope to bring this up, because “saving the planet” cannot be considered an a priori good when the costs associated with it make the alleviating of human suffering more expensive. This is something climate alarmists need to hear.

What I didn’t like: I thought the pope gave short shrift to the important work being done in cities, especially in the developed world. He painted a dire picture of urban environments, but in fact many are making great strides on sustainability. And the advantage to this city-by-city approach is that, unlike one grand master plan for the whole world, it allows localities to be laboratories for new technology. Buying into one, top-down approach risks curtailing significant innovation on the local level.

David Marcus is a senior contributor to The Federalist and the artistic director of Blue Box World, a Brooklyn-based theater project.

Maureen Mullarkey

What is there to like in this gargantuan exposé of a papal mind outpaced by its own ambitions? All I can do is distinguish between levels of distaste.

There is little to admire in this meandering pronunciamento. Yes, there are obligatory restatements of the Catholic Church’s traditional positions on the sanctity of life, the primacy of the family, and rejection of abortion. All that is new here is the rejection of gender ideology, a phenomenon worthy in itself of magisterial attention. But these insertions of orthodoxy are the vehicle for insinuating wholesale surrender to pseudo-science and the eco-fascism derived from it.

“Laudato Si” is a Trojan Horse that justifies the church’s hierarchical embrace of left-wing ideology and the powers that promote it. Affirmations of standing doctrine deflect dissent and veil the bankruptcy of the document’s irrational commitment to the climate change narrative, including its demand for the abolition of fossil fuels. The document hands a bouquet to all statists, collectivists, crackpot world-improvers, and antagonists to free enterprise, even to freedom itself. Every authoritarian jackal and central planner on the planet can pluck a bloom from it.

Under cover of Franciscan piety, Pope Francis assimilates the Catholic Church to the creation of global authorities with enforcement powers that trump national sovereignty. “Laudato Si” is a scandal.

Maureen Mullarkey is a painter who writes on art and culture. She blogs at First Things.

Ben Domenech

If the only scientist invited to speak at the Vatican at the presentation of the encyclical indicates the direction of Pope Francis’s sentiments, or those of his handlers, it would say a lot about the source for the more Gaia-esque portions of the document. “One of the presenters at the press conference today in Rome was John Schellnhuber, an atheist German, who has said America must reduce its CO2 emissions to 0 by 2020 (an impossibility), and that we need to reduce global population to the earth’s ‘carrying capacity’ of under 1 billion (which would require outrages against humanity). Francis probably doesn’t countenance that, but he takes it as settled—and urgent—that catastrophic climate change is now underway and the nations of the world, singly and together, need to take drastic steps to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. His recommendations include everything from vast reorganization of the global economic order and stringent international agreements on greenhouse gas emissions, to everyday matters such as restricting the spread of air conditioners and adopting a more ascetic lifestyle by people around the world.”

Reading the encyclical—which is worth doing—it seems to me to be a very uneven document, which swings between sloppy expressions—“Jesus took up the biblical faith in God the creator,” warnings against “tyrannical anthropocentrism”—and a few good portions. Even though I disagree with it, I liked this portion:

“[W]hen media and the digital world become omnipresent, their influence can stop people from learning how to live wisely, to think deeply and to love generously. In this context, the great sages of the past run the risk of going unheard amid the noise and distractions of an information overload. Efforts need to be made to help these media become sources of new cultural progress for humanity and not a threat to our deepest riches.

“True wisdom, as the fruit of self-examination, dialogue and generous encounter between persons, is not acquired by a mere accumulation of data which eventually leads to overload and confusion, a sort of mental pollution. Real relationships with others, with all the challenges they entail, now tend to be replaced by a type of internet communication which enables us to choose or eliminate relationships at whim, thus giving rise to a new type of contrived emotion which has more to do with devices and displays than with other people and with nature. Today’s media do enable us to communicate and to share our knowledge and affections. Yet at times they also shield us from direct contact with the pain, the fears and the joys of others and the complexity of their personal experiences. For this reason, we should be concerned that, alongside the exciting possibilities offered by these media, a deep and melancholic dissatisfaction with interpersonal relations, or a harmful sense of isolation, can also arise.”

But that’s not, of course, what this encyclical is about. It is about climate change. That has already been decided. The media will dutifully ignore any of the good theological statements in the document, and put the pope to use as a method of bringing pressure on politicians on issues they care about. Already a major ad push and attendant activist campaigns, months in their construction, are being blasted out across the Internet and in streaming ads today calling for political action consisting of the typical grab bag of anti-capitalist policies. One of the first I saw included a push for carbon credits, which the pope actually opposes. Who cares? What really matters is not what the document actually says, it is how it can be used by those who have been waiting eagerly to use it.

The day before the Vatican gave Schellnhuber the mic, Gallup released a poll showing Americans’ confidence in organized religion has hit a new low. It now ranks fourth in trust, behind the military, small businesses, and cops. Surely talking about climate change and becoming a leading figure on the topic will help with that, in much the same way that putting nuclear policy front and center rejuvenated the Mainline.

Ben Domenech is the publisher of The Federalist.