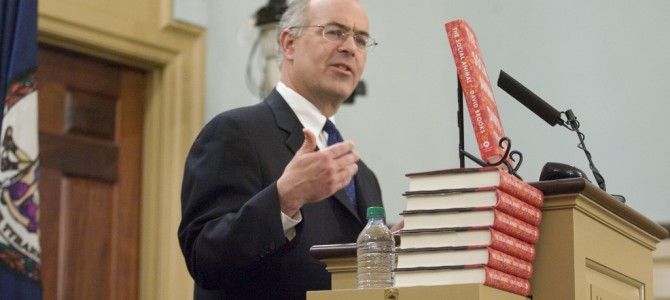

New York Times columnist David Brooks might describe the goal of his latest book in more humble terms but, as his title implies, using social science to navigate “The Road to Character” is no small undertaking.

The book hinges on the juxtaposition of “resume” virtues and “eulogy” virtues. The “resume” virtues are quantifiable, achievement-oriented, and measure up to an extrinsic standard of success: get good grades, build out extracurriculars, increase earning potential, earn a higher degree, work up the corporate ladder, buy a bigger house, network with the right people. Brooks basically says that approaching life this way will crush your soul. He defends the “eulogy” virtues by asking what you want people to say about you when you die. These are more intangible qualities: Are you a good person? Does your life have worth? Do you know what matters most at the end of the day?

Speaking last week in Washington DC, Brooks confessed that he wrote the book in an attempt to save his own soul. Evoking Dante, as does Rod Dreher in his latest, “How Dante Can Save Your Life,” Brooks’s “The Road to Character” depicts a soul’s journey to God. For Brooks, he’s saving his soul through writing. For us to save our souls, he suggests we write our eulogy today. In other words, get ready to die.

Honor Suffering, Not Just Success

Brooks certainly tells a fine story. He brings social science to life with embodied, vivid narrations of the lives of characters and their moral choices to prove it’s what’s on the inside that counts. Here Brooks reveals that he knows something deeply true about human nature: people change because of the lives and examples of other people. We are inspired by the lives of the saints, and not only by their words.

Brooks reminds us that the soul is the most important thing we have. But Brooks is also doing two other very significant things of cultural and political relevance worth caring about.

First, Brooks indirectly suggests a new, non-therapeutic approach to psychology and social science. The widespread approach to psychological problems—psychologists don’t mention the soul—is to teach that we are special. We are taught that if we do the right things, life will turn out okay. Get good grades, and you will succeed.

Our culture ties value to performance, so struggle becomes linked with failure. Then, when life doesn’t pan out the way we anticipated, American culture has no real framework to address pain and suffering other than self-esteem-boosting therapy, which tends only to prolong one’s steep in narcissism, the surest path to misery. Deprived of a cohesive moral compass, Americans are easily lost in noise and competition of academia, career, social media, and entertainment.

In the place of prevalent therapeutic models, Brooks revives an understanding of sin or faults within the self. He talks about redemption and grace. He paints a beautiful picture of humility and a view beyond the self, the beholding of truth and beauty and responding with gratitude. Suffering then becomes a valuable experience that purges and enlightens the soul.

Making Morality Palatable Again

Second, the best thing about Brooks’ recent work in this vein is that he is mainstreaming talk of morality and making it palatable to wide, non-religious audiences. This is an invaluable achievement in that it raises talk about souls, morality, humility, and love in the public conversation as credible, workable, viable ideas. This is reminiscent of the “natural law” approach and is probably one of the best ways to dialogue with the millennial generation.

This is all good, but making morality palatable to the masses inevitably raises obvious questions for Brooks. Upon first encountering Brooks’ framework, many people might ask why this is a big deal. Character is nothing new. The classical and Christian traditions contain deep wells of thought on virtue, morality, and how to live a good life. Brooks isn’t doing anything special.

However, it’s not that Brooks is breaking new ground so much as resurrecting a version of classical virtue and Christian spiritual disciplines. Ancient Romans used several words to understand character: natura, or one’s essential nature or substance; mos, or the customs and habits of a people; and virtus, which meant strength or manliness, and from which we derive the word virtue. Classical philosophers and church fathers knew that to be fully human and to live a good life, one had to order one’s soul in accordance to reality, per Aristotle, and the love of God, per Augustine.

A Sip of Water in a Desert

It’s an indictment of our culture that his book is so provocative. Modern America is an aberration in its deviation from the general moral norms of the last two millennia. If we have to consciously think about being humble, let alone need national conversations on humility, we’ve fallen far, indeed. Brooks’ depiction of morality may be incomplete and lack nuance, but overall can only be water in the desert.

At times, Brooks himself reflects both the best and worst tendencies of modern American morality. To complement publication of “The Road to Character,” Brooks just published an op-ed on a “Moral Bucket List” which is worthy of both admiration and scorn.

Again, it’s commendable that he mainstreams and addresses morality in the public conversation. On the other hand, here he reduces and markets morality as a checklist. Great moments of moral testing or salvific suffering tend just to come to us and are not usually experiences we can seek out and check off. In that case, morality becomes about accomplishment and achievement, precisely the things Brooks wants to eschew. Brooks is walking a tightrope between self-awareness and embodying the superficial aspects of the amoral culture he’s railing against.

It’s also true that the hidden, everyday stuff of life often quietly forms character. Brooks raises morality to an elevated plain of almost-grand experience. This is valuable and attractive, but real moral decisions and growth take place in the mundane tasks of earthly existence—and sometimes in faithfully executing the more “resume-oriented” tasks. Developing character is hard and requires many little “deaths” to the self. It takes a long time to grow a soul, to say nothing of the tireless effort involved in saving it.

Is Character Possible in a Vacuum?

The most pressing question in the mainstream cultural conversation on character and morality is this: Can morality practically exist outside of the robust practice of a sincere religious faith? Are there institutions or resources outside of churches to inculcate and nurture the kind of morality and character Brooks is talking about?

Unfortunately, if you want prescription in Brooks, you will likely be frustrated. Brooks is intentionally nonsectarian. He’s not going to satisfy Christians or Jews who are theologically knowledgeable and committed to their faiths. That’s not to say that they won’t wring enjoyment or learn from Brooks. Religious readers will, say, appreciate the book’s inclusion of Augustine and laugh knowingly at Brooks’ characterization of Monica as the quintessential helicopter mom in Augustine’s moral development. But overall Brooks will not satisfy the philosophically minded and nuanced.

From a sectarian perspective, Brooks isn’t offering up anything new under the sun, then, either. But, again, Brooks vision here is relevant because it’s timeless. In “The Republic,” Plato connects the human soul with the soul of the city. The soul’s health correlates to the city’s health. A well-ordered soul is akin to a well-ordered republic. The soul of the city reflects the souls of the individuals within the city. If there’s order in souls, there’s order in the city. Plato told us millennia ago that the soul matters more than outward success. Helping readers see the Platonic connection between healthy souls and healthy societies seems to be exactly what Brooks hopes to achieve.

Ultimately, his book is wise reflection on why character is more important than external success and why moral choices do more to shape quality of life than achievements. Brooks shows how morality and virtue form character, and by injecting these big words into the public conversation he provides a needed warning to the most self-centered generation. All the while, Brooks gently recalls us to an ancient wisdom and way of living the good life.

“The Road to Character” isn’t perfect, and it’s too much to expect it to be a roadmap to salvation. But it is a timely and insightful meditation on the importance of character. In an era that venerates superficial accomplishments, that is no small achievement.

Editor’s note: CSPAN will air a discussion with Brooks about this book May 2. View live online here.