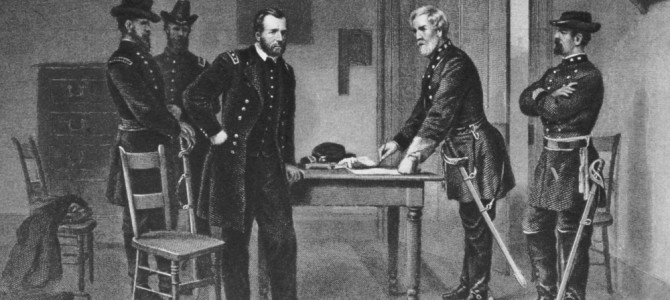

Today marks the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Appomattox, the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, which effectively ended the Civil War. Ragged fighting would continue for more than a year, mostly out west, but for most of the country the surrender at Appomattox confirmed the victory of North over South and the dawn of a new era in the republic.

The sesquicentennial of the war’s end is of course notable in an historical sense, but it’s especially important now because it comes during a time of growing national division. The Obama presidency, far from ushering in an era of post-partisanship, has deepened the rift between liberals and conservatives and heralded a new era of rancorous partisanship in Washington DC, and revived culture wars across the country.

Last week’s unhinged outrage over Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which the Left decried as a license for religious business owners to discriminate against gay customers and the Right defended as a necessary protection for the devout, will perhaps be eclipsed this week by planned protests of another police shooting in which a white officer shot and killed an unarmed black man in North Charleston, South Carolina.

Of course, all this pales in comparison to the Civil War, and also to other periods of national unrest like the race riots of the 1920s or the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. But the anniversary of Appomattox should hold a special place for us precisely because it marked the end of an unprecedented cataclysm. Indeed, from our vantage point it’s hard to fathom the destruction our Civil War visited upon the country. In four years of fighting, a combined 620,000 men died or were killed in active service. As a percentage of today’s population, those losses would amount to more than 6 million. An apocalypse.

Grace in Victory and Defeat

If ever the vanquished had reason to be bitter, or a victor had cause to be punitive, it was Lee and Grant. Yet their comportment at Appomattox stands today as a testament to the ideals of national reconciliation, goodwill, and honor and respect for one’s enemy. In his epic narrative history of the Civil War, Shelby Foote recounts two instances from Appomattox that suggest Lee and Grant were both thinking of the greater good, keenly aware that an enduring peace depended in part on their humility and generosity.

Early on the morning of April 9, Lee called a conference with his generals so they could give their opinions on surrender. All of them concurred that under the circumstances surrender was the only option, except the young Brigadier General Edward Alexander, who, writes Foote, “proposed that the troops take to the woods, individually and in small groups, under orders to report to the governors of their respective states. That way, he believed, two thirds of the army would avoid capture by the Yankees.”

Lee gently rebuked Alexander, reminding him, “We must consider its effect on the country as a whole.” The men, he said, “would be without rations and under no control of officers. They would be compelled to rob and steal in order to live. They would become mere bands of marauders, and the enemy’s cavalry would pursue them and overrun many sections that may never have occasion to visit. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from.” Alexander would later write: “I had not a single word to say in reply. He had answered my suggestion from a plane so far above it that I was ashamed of having made it.”

Grant’s terms of surrender were remarkable for their leniency on the Confederate Army. Although the rebels would be required to turn over their arms, artillery, and private property, Grant added an impromptu final sentence: “This will not embrace the side arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage.” At Lee’s request, he also allowed Confederate cavalrymen and artillerists who owned their own horses and mules to keep them, reasoning that most were small farmers and would not be able to put in a crop “to carry themselves and their families through the next winter without the aid of the horses they are now riding.”

At this crucial moment, it was most important to Grant and Lee that the soldiers return home safely and get on with civilian life as soon as possible. Returning to his men, Lee told them, “I have done the best I could for you. Go home now, and if you make as good citizens as you have soldiers, you will do well, and I shall always be proud of you.” En route back to his headquarters, Grant heard salutes and cheering begin to rise up from nearby Union batteries. He sent orders to have them stopped. “The war is over,” he said. “The rebels are our countrymen again.”

Wiping Our Memory Is a Fool’s Errand

Some on the Left want to celebrate Appomattox for rather different reasons, and by different means. Brian Beutler at The New Republic suggests grinding our collective memory of the Confederacy to dust. We should allow the graves of Confederate soldiers to crumble, remove the Confederate memorial at Arlington National Cemetery, and divest the federal government from maintenance of Confederate monuments across the country. “We aren’t being polite to anyone worthy of politeness,” he writes, “or advancing any noble end, by continuing to honor traitors in this way.”

This crude way of thinking about the past betrays an ugliness in the way one thinks about the present. Imagine what Beutler thinks of present-day enemies on the Right. He writes of “Obama’s America” as a place where we’re strong enough to be introspective, a place in which “an establishment worthy of preservation is continually improved by righteous internal forces.” Secessionists, and even the memory of them, have no place in this America, he says, and so we should mark Appomattox only as a celebration of the triumph of good over evil, simple as that.

But Beutler misunderstands, deeply, why wars are remembered at all, and why the dead of our Civil War, North and South alike, merit special remembrance and honor. In a speech delivered on Memorial Day, 1884, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, who had seen much combat as a Union soldier, sought to explain why Memorial Day “ought to have a meaning also for those who do not share our memories.” Young people must first desire to understand the significance of the war. Since you can’t argue someone into desiring a thing, the best way to impart such a desire, he said, was through emotion:

Feeling begets feeling, and great feeling begets great feeling. We can hardly share the emotions that make this day to us the most sacred day of the year, and embody them in ceremonial pomp, without in some degree imparting them to those who come after us. I believe from the bottom of my heart that our memorial halls and statues and tablets, the tattered flags of our regiments gathered in the Statehouses, are worth more to our young men by way of chastening and inspiration than the monuments of another hundred years of peaceful life could be.

Holmes understood well what seemingly has never occurred to Beutler: those Confederate monuments do not stand as tributes to the righteousness of the South’s cause, nor were they erected to mollify the South after the war “for the unspoken purpose of making the reunion stick.” The Civil War and its memory can’t be thus reduced. The monuments were built so that future generations would remember the war and come to understand it on a deeper level, not just as a struggle over slavery, but as a collective, sustained act of conviction and faith—on both sides. “There is nothing remarkable about war destroying youthful illusions or shattering the nerves of strong men,” wrote Matthew Berke in a review of Ken Burns’ 1991 documentary of the war. “What really requires explanation, though, is why, in such an environment, so many men maintained such a high level of duty, courage, and devotion to cause.”

Respect Those Who Give All for Their Beliefs

Holmes, a Union veteran, said that he and his comrades, although convinced that the Union was indissoluble, “equally believed that those who stood against us held just as sacred convictions that were the opposite of ours, and we respected them as every man with a heart must respect those who give all for their belief.”

No doubt those of Beutler’s cast of mind will protest that the convictions Southerners held were racist and impossible to respect, so we should not have to be reminded of them. One could reply that most Confederate soldiers did not own slaves and considered their cause to be a defense of home and hearth, just as most Union soldiers did not believe they were fighting to end slavery but to preserve the Union. But it’s no use talking about history to such people. Context and nuance are not their concern. Their concern is to purge and forget, to hide from history and its troubles.

In the last scene of Burns’ documentary, Foote reads a quote from the memoirs of a Confederate soldier, who, upon sitting down to write, Foote says, “found that reliving the war in words made him wish he could relive it in fact, and he came to believe that he and his fellow soldiers, gray and blue, might one day be able to do just that; if not here on earth, then afterwards in Valhalla.” The quote reads:

Who knows, but it may be given to us, after this life, to meet again in the old quarters, to play chess and draughts, to get up soon to answer the morning roll call, to fall in at the tap of the drum for drill and dress parade, and again to hastily don our war gear while the monotonous patter of the long roll summons to battle? Who knows but again the old flags, ragged and torn, snapping in the wind, may face each other and flutter, pursuing and pursued, while the cries of victory fill a summer day? And after the battle, then the slain and wounded will arise, and all will be talking and laughter and cheers, and all will say: Did it not seem real? Was it not as in the old days?

What Appomattox Means for Us

To mark Appomattox, or honor the Confederate dead, or preserve Confederate monuments, is not “spitshining the Confederacy,” as Beutler insists, but keeping alive the memory of our ancestors, good and bad, in hopes of understanding what they went through, and why, and what it means for us today.

Beutler thinks it’s obvious what it means: we should boldly and officially condemn the Confederacy and stamp out its memory. He thinks this would be a robust act of introspection and self-criticism. But, really, it would be a way to hide from history.

The urge is perhaps understandable. History can be painful and arduous, and comprehending something like our Civil War is a lifelong task. Bob Dylan once wrote that if you want to understand America then you have to understand the Civil War, and he was right. It won’t do to forget or to hide. There will always be those who want to hide from history, but they should not be allowed to hide it from the rest of us.