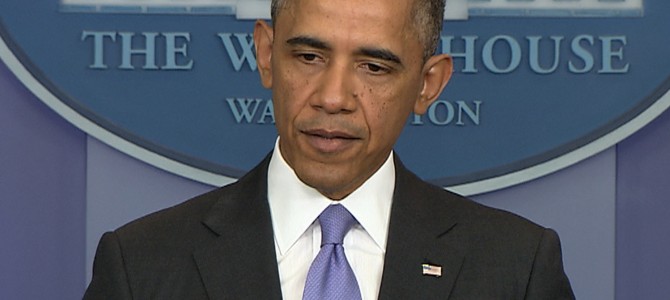

One of the consequences of Barack Obama’s presidency will be to discredit the foreign policy of the “humanitarians.” It won’t be because people think it’s bad to feel compassion for the suffering of others. It will be because the loudly declared compassion of the humanitarians is revealed, in practice, as ineffectual posturing adopted as a substitute for actual strategy.

The latest occasion for this is the president’s announcement that he has authorized American air strikes to stop the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria from expanding to swallow up Iraqi Kurdistan. What triggered this announcement? ISIS had begun to overrun Kurdish border positions and threatened to wipe out about 40,000 Christians and Yezidis (leftover Zoroastrians) who have long enjoyed a safe haven thanks to Kurdish broadmindedness on the subject of religion.

(By the way, ISIS is now calling itself just the “Islamic State” and demanding the loyalty of the entire Muslim world, but I’ll continue adding the “Iraq and Syria” part because those are the only places they can actually assert any authority. Plus, it makes for a better acronym.)

President Obama declared here that the US “cannot turn a blind eye” to the “genocide” of the Yezidis. Yes, this is from the same man who turned a blind eye while hundreds of thousands of people have been brutally wiped out, tortured, and starved in Syria. But 40,000 face a similar threat in another spot, so he lets loose a few American bombs. That’s what impresses me most about this: the capriciousness of Obama’s humanitarianism, and also its episodic nature, as if it is all driven by a response to temporary political forces and the desire to avoid bad press coverage for a few news cycles, with no bigger, long-range thought behind it.

It reminds me of Obama’s approach to the war in Libya. When Gaddafi’s thugs were driving east toward Benghazi and vowing to kill everyone there, finally Obama authorized American action—but once the conflict was over and Gaddafi was overthrown, he dropped the issue. He took no interest in Libya, made no plan for how to help stabilize the country, and devoted no resources to the issue. As a result, he ended up losing an ambassador and three other American in Benghazi, and now our entire diplomatic mission has bugged out as the country dissolves in a new civil war.

President Obama’s State Department has become notorious for its “hashtag diplomacy,” using Twitter messages to impress upon everyone how much the administration cares about a particular issue—#UnitedForUkraine or #BringBackOurGirls—as cover for the fact that we’re not really doing anything about it.

Back in Iraq, Jacob Siegel succinctly describes how this current disaster was a result of the failure of President Obama’s previous approach to Iraq: “What had been the US policy—to rely on local forces to contain ISIS while waiting for a new Iraqi government to reach a political solution—is finished.” He goes on to warn that a few airstrikes are not likely to accomplish anything, either. No kidding.

This fits the Obama pattern, in every overseas conflict, of doing just the bare minimum necessary to be able to talk himself into the hope that it will all work itself out somehow, that somebody else will step up and America doesn’t have to take a stand. American disengagement from the world is his goal, the only consistent theme of his administration. These fits of humanitarian intervention are just temporary punctuation within an overall strategy of withdrawal.

Remember the old expression that if you fail to plan, you plan to fail? The reverse is also true: if you plan to fail, you fail to plan. If your goal is American irrelevance, then you won’t make any plans for how the US can successfully shape events to serve our interests. So we don’t see much evidence of a long-term plan here. Obama announced his new war in Iraq by promising that “I will not allow the United States to be dragged into fighting another war in Iraq.” This war-that-is-not-a-war approach indicates the absence of any strategy in Iraq.

To establish a strategy in Iraq is to establish a long-term end result that America wants to achieve, to pick sides in the current fight, and to commit to doing whatever is necessary to achieve the desired result. In this case, America cannot tolerate the existence of a brutal terrorist state like ISIS, given that this is precisely the kind of organization that mounted the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Even if we act now, I believe it is only a matter of time before ISIS-backed terrorists, probably US or European citizens who were recruited for the jihad, attempt a significant terrorist attack on the United States. They will no doubt cite the current air strikes as provocation, so we might as well get something substantial out of them. Rather than a few airstrikes to protect one small enclave, we need an effort which includes continued airstrikes coordinated by hundreds of American special forces embedded with Kurdish troops at the front—coupled with some serious ultimatums to the central government in Baghdad to get rid of its incompetent, sectarian, Iranian-backed leadership and to reincorporate the Sunni tribes alienated by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki.

But this requires a president willing to set the strategic objective of defeating ISIS, as opposed to just containing its spread and alleviating the latest humanitarian crisis caused by its brutal rule.

That’s the underlying problem with “humanitarian” foreign policy. We cannot react to every humanitarian crisis in the world, and most of the time, such a crisis is merely a symptom of a much bigger problem. But “humanitarians” react to these symptoms ad hoc and emotionally, with no consistency and no follow-up. Often, as in the case of Iraq, this seems to be intended as guilty compensation for the strategic indifference that allowed the country to descend into bloody chaos in the first place.

What would a strategic humanitarianism entail? It would involve a long-term campaign to eliminate the kind of terrorist groups and dictatorial regimes that commit acts of mass slaughter and to replace them with governments that represent their people and have some respect for their rights. Such an approach is generally know by the label “neoconservatism.”

What would be better would be the big-picture approach of the neoconservatives—one that addresses the underlying causes of global threats rather than just the symptoms—combined with a focus on regimes and terrorist groups who pose the greatest threat to the United States. Which would be, more or less, the foreign policy of George W. Bush—who actually did achieve, for a while, a period of peace and stability in Iraq that was consistent with American interests.

But we couldn’t have that now, could we? Better to throw around a few “humanitarian” bombs to make ourselves feel better for a while.

Follow Robert on Twitter.