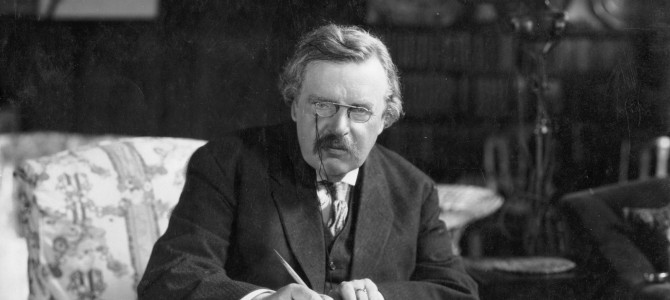

G.K. Chesterton is practically infinitely quotable, a fact that I have put to the test over the past several years curating the Daily Chesterton Quote site and service.

However, when you combine such a prolific writer with a legacy over a century old, plus the Internet, you stumble upon a few misattributed quotes. Some of these have become incredibly popular, taking on a life of their own; but there is no evidence that G.K. Chesterton actually said these things.

Even the well-read experts have mistakenly repeated the misquotes; I am almost certain I have repeated some of these myself.

I had thought of doing a series of Chesterton misquotes in a “Not said by Chesterton” series on GKChestertonQuote.com, but that could just add to the confusion.

“Love means loving the unlovable – or it is no virtue at all.”

The only place I can find attribution on this is the American Chesterton Society, which states it comes fromHeretics – but searching the etext does not turn up any parts of the phrase.

Everyone else cannot seem to find this quote in GKC’s works, even though it comes in a few different forms, such as, “Love means to love that which is unlovable, or it is no virtue at all; forgiving means to pardon that which is unpardonable, or it is no virtue at all,” or “ To love means loving the unlovable. To forgive means pardoning the unpardonable. Faith means believing the unbelievable. Hope means hoping when everything seems hopeless,” or “Love means to love that which is unlovable; or it is no virtue at all.”

The closest thing I have been able to find is in Orthodoxy: “Stated baldly, charity certainly means one of two things–pardoning unpardonable acts, or loving unlovable people.”

“Fairy tales are more than true — not because they tell us dragons exist, but because they tell us dragons can be beaten.”

This one really took on a life of its own, and in recent times. This brief, succinct, beautiful expression is actually first found in the epitaph of Coraline by Neil Gaiman.

This has sparked quite a literary issue on the Internet, but Gaiman actually set the record straight on his blog:

It’s my fault. When I started writing Coraline, I wrote my version of the quote in Tremendous Trifles, meaning to go back later and find the actual quote, as I didn’t own the book, and this was before the Internet. And then ten years went by before I finished the book, and in the meantime I had completely forgotten that the Chesterton quote was mine and not his. I’m perfectly happy for anyone to attribute it to either of us. The sentiment is his, the phrasing is mine.

If you read enough Chesterton and his critics, GKC did the same thing; he could read an entire book in minutes, and often wrote from memory. While exceptional, it was not perfect. So Gaiman “pulled a Chesterton” while paraphrasing GKC.

It is worth mentioning that Gaiman is a big fan of Chesterton, and GKC has directly influenced Gaiman’s Sandman, Coraline, Good Omens, Neverwhere, and probably a lot of other books.

Here is the original that Gaiman cites, from The Red Angel in Tremendous Trifles – quoted a bit more at length than usual for context:

The timidity of the child or the savage is entirely reasonable; they are alarmed at this world, because this world is a very alarming place. They dislike being alone because it is verily and indeed an awful idea to be alone. Barbarians fear the unknown for the same reason that Agnostics worship it– because it is a fact. Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.

Exactly what the fairy tale does is this: it accustoms him for a series of clear pictures to the idea that these limitless terrors had a limit, that these shapeless enemies have enemies in the knights of God, that there is something in the universe more mystical than darkness, and stronger than strong fear. When I was a child I have stared at the darkness until the whole black bulk of it turned into one negro giant taller than heaven. If there was one star in the sky it only made him a Cyclops. But fairy tales restored my mental health, for next day I read an authentic account of how a negro giant with one eye, of quite equal dimensions, had been baffled by a little boy like myself (of similar inexperience and even lower social status) by means of a sword, some bad riddles, and a brave heart. Sometimes the sea at night seemed as dreadful as any dragon. But then I was acquainted with many youngest sons and little sailors to whom a dragon or two was as simple as the sea.

“A man knocking on the door of a brothel is looking for God.”

I heard this one most recently in a Bible study; but it was actually from author Bruce Marshall in The World, The Flesh, and Father Smith, in which the quote appears, “the young man who rings the bell at the brothel is unconsciously looking for God.“

Guess it sounded Chestertonian and someone got it mixed up.

“If there were no God, there would be no atheists.”

This is going to sound like nitpicking, but a single letter changes a word, and a changed word can change the meaning.

The correct quote, from the essay Too Simple to Be True, collected in Where All Roads Lead is “If there were not God, there would be no atheists.”

The misquote helps fuel the misconception that GKC’s point was that with out a Creator, there would be no one to deny Him. That is a bit pedantic for Chesterton, and the meaning of the quote is best expressed in the context:

“Atheism is, I suppose, the supreme example of a simple faith. The man says there is no God; if he really says it in his heart, he is a certain sort of man so designated in Scripture. But, anyhow, when he has said it, he has said it; and there seems to be no more to be said. The conversation seems likely to languish. The truth is that the atmosphere of excitement, by which the atheist lived, was an atmosphere of thrilled and shuddering theism, and not of atheism at all; it was an atmosphere of defiance and not of denial. Irreverence is a very servile parasite of reverence; and has starved with its starving lord. After this first fuss about the merely aesthetic effect of blasphemy, the whole thing vanishes into its own void. If there were not God, there would be no atheists.”

Chesterton’s point was not that atheists would not exist without God to create them, but to point out that atheism only subsists because it is a blasphemy or rejection of something real; after all, there is no serious organization or movement that is denying the existence of unicorns or leprechauns.

“Meaninglessness does not come from being weary of pain. Meaninglessness comes from being weary of pleasure.”

A reader asked me about this quote, which he had heard from Ravi Zacharias. It seems to be a repeat of the Gaiman fairy tale quote, where someone beautifully paraphrased a longer, more involved Chesterton quote.

G.K. Chesterton did state in The Everlasting Man:

“Pessimism is not in being tired of evil but in being tired of good. Despair does not lie in being weary of suffering, but in being weary of joy. It is when for some reason or other the good things in a society no longer work that the society

begins to decline; when its food does not feed, when its cures do not cure, when its blessings refuse to bless. We might almost say that in a society without such good things we should hardly have any test by which to register a decline; that is why some of the static commercial oligarchies like Carthage have rather an air in history of standing and staring like mummies, so dried up and swathed and embalmed that no man knows when they are new or old.”

and in Charles Dickens (which I wrote about here):

“There are some men who are dreary because they do not believe in God; but there are many others who are dreary because they do not believe in the devil… The full value of this life can only be got by fighting; the violent take it by storm. And if we have accepted everything we have missed something — war. This life of ours is a very enjoyable fight, but a very miserable truce.”

“When people stop believing in God, they don’t believe in nothing — they believe in anything.”

Wikiquotes has explanation of this and the other form it takes, “The first effect of not believing in God is to believe in anything.”

This quotation actually comes from page 211 of Émile Cammaerts’ book The Laughing Prophet : The Seven Virtues and G. K. Chesterton (1937) in which he quotes Chesterton as having Father Brown say, in “The Oracle of the Dog” (1923): “It’s the first effect of not believing in God that you lose your common sense.” Cammaerts then interposes his own analysis between further quotes from Father Brown: “‘It’s drowning all your old rationalism and scepticism, it’s coming in like a sea; and the name of it is superstition.’ The first effect of not believing in God is to believe in anything: ‘And a dog is an omen and a cat is a mystery.’” Note that the remark about believing in anything is outside the quotation marks — it is Cammaerts.

“What is Wrong With the World?” “Dear Sirs, I am.”

This seems to be the penultimate Chesterton myth, in the truest sense of the word. It was even the inspiration for a documentary entitled I Am that came out a few years ago. However, while it might be full of truth and Chestertonian wit, no one can find it.

The Times and other English papers have been searched through their archives, and yet no one can find the fabled essay request or the incredibly short response from GKC. It could be that the letter was written and not published, but as of the time of this writing no one seems to be able to find the source of the story or any evidence that it is true.

Many theories surround the fact that Chesterton did write a book called What is Wrong With the World. In the dedication, GKC writes:

“I originally called this book “What is Wrong,” and it would have satisfied your sardonic temper to note the number of social misunderstandings that arose from the use of the title. Many a mild lady visitor opened her eyes when I remarked casually, “I have been doing ’What is Wrong’ all this morning.” And one minister of religion moved

quite sharply in his chair when I told him (as he understood it) that I had to run upstairs and do what was wrong, but should be down again in a minute. Exactly of what occult vice they silently accused me I cannot conjecture, but I know of what I accuse myself; and that is, of having written a very shapeless and inadequate book, and one quite unworthy to be dedicated to you. As far as literature goes, this book is what is wrong and no mistake.”

In a review of the book, St. John Ervine wrote, “‘The book is called ‘What’s Wrong with the World,’ by G.K. Chesterton: it should have been called, ‘What’s Wrong with the World’ is G.K. Chesterton’.”

If there are any new sources that are discovered that validate these quotes, however, I would very much like to hear about it! If you want to do your own research on Chesterton quotes, check out the G.K. Chesterton search engine here.