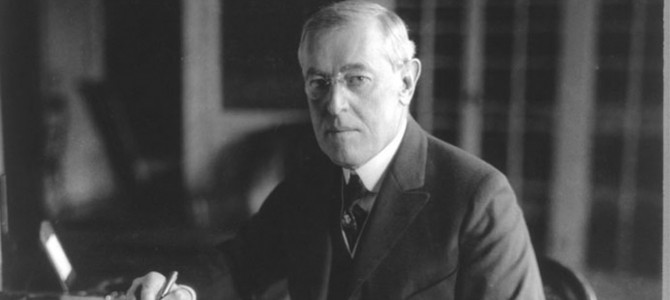

In 1913, Woodrow Wilson claimed that the pace of change in economic life was so rapid that “nothing is done in this country as it was done twenty years ago.” As he drew out the consequences of this radical transformation, he argued that it “calls for creative statesmanship as no age has done since that great age in which we set up the government under which we live…”

The Progressive rallying cry for the century since has been a series of appeals to meet the needs of ever-revolutionizing circumstances, to stay in step with history, and create the government apparatus–power and institutions–necessary to make room for the next wave of “creative statesmanship.”

Yet along the way, the most basic, permanent functions of government have been too often neglected, trivialized, or performed by a faceless bureaucracy that moves from one stack of paper, email, or memo to the next. Leaders are increasingly becoming political front men tending to matters of public relations through the use of rhetorical device.

Some would contend that there is nothing new under the sun: this has always been the way of politics. Who but an Alexander, a Caesar, and a Napoleon was better prepared to communicate affairs of state to their political communities? Add to this that our leaders today operate in a political environment where communication advances have produced a media-driven politics, and you have a solid defense of wag-the-dog statesmanship.

As recent events have illustrated, however, this does not come without a price–nor, as we’ll see without a viable alternative. Jay Carney and friends were in spin overdrive last week with the release of an email that seemed to suggest the White House was behind Susan Rice’s erroneous claim that the Benghazi attack had been inspired by a YouTube video. On Wednesday, Carney claimed that the email was not about Benghazi at all, but about the broader protests occurring at the same time in a number of Middle Eastern nations–which, as one reporter pointed out Thursday, made it an odd email to include in a response to a Freedom of Information Act filing requesting documents related to Benghazi. Better ask the State Department about that, replied Carney.

As the Administration passes the hot potato from the White House to the State Department to the CIA and back, much to the delight of the longtime actors and voyeurs of “As Washington Turns,” the most fundamental failure in the Benghazi attacks all but disappears from view. Hidden in plain sight just below the email’s “Internet video” language is the real heart of the matter: “To show that we will be resolute in bringing people who harm Americans to justice, and standing steadfast through these protests . . .” Twenty months later, whatever the Administration’s degree of resolve, justice has yet to be done.

The same problem is evident in the debate over Secretary of State John Kerry’s recent remarks concerning Israel. After suggesting in a private Trilateral Commission meeting that the nation might devolve into an “apartheid state” in the absence of adopting his preferred two-state solution to its ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, Mr. Kerry expressed regret–principally that his words had opened him up to criticism. Again, the substance of the matter disappeared from view, while Mr. Kerry waxed indignant on the “partisan, political purposes” that had inspired his critics. In concluding his press release with a citation of members of the Israeli government who have also invoked the specter of “apartheid,” Mr. Kerry snuggled into his warm political covers, either oblivious to or simply negligent of the fact that he had committed more than a rhetorical faux pas.

Leaving aside the fact that bad demographic data had led him to pose a false choice for “one-state” Israel between oppressing a future Palestinian majority or being subjugated by one, Mr. Kerry’s remarks before the Trilateral Commission elites, even if never made public, would increase the pressure on Israel to accept not just a two-state solution, but his…now. America’s chief diplomat, in other words, should understand that such remarks cannot be understood as idle academic speculation (“What is the universe of possible futures for Israel?”), but as a means of excluding any alternative to his plan and, thereby, undercutting Israeli efforts to negotiate terms more compatible with her long-term security.

The Administration’s pose in both cases rests upon the pragmatic philosophical premise that the claims it makes matter little unless they produce practical differences. Carney, Kerry, and others presume that no claim is beyond repair if they have a new claim, the next press conference, and another news cycle at their disposal. If you are always prepared to use words to sally, you can always stay ahead of whatever practical difference your words make. Or translated into Obamian millennial speak: that was two years ago, dude.

Thoroughly grounded in the alternative to this alternative reality, aka the real world, James Madison wrote in Federalist 42 that “[i]f we are to be one nation in any respect, it clearly ought to be in respect to other nations.” What follows this claim is a straightforward, even pedestrian defense of the diplomatic powers lodged in the national government by the Constitution–the ability to appoint and receive ambassadors, consuls, and the like.

Unfortunately, the Articles had failed to specify these powers carefully, leaving out any mention of consular officials and therefore suggesting, in keeping with its stated principle of hyper-strict construction, that none but (high-level) ambassadors could be appointed or received by the government.

Progressives at least might ask: why this eyestabby, worse-than-watching-paint-dry excursion into the minutiae of a dusty old, long-replaced government charter? Madison explains:

A list of the cases in which Congress have been betrayed, or forced by the defects of the Confederation, into violations of their chartered authorities, would not a little surprise those who have paid no attention to the subject; and would be no inconsiderable argument in favor of the new Constitution, which seems to have provided no less studiously for the lesser, than the more obvious and striking defects of the old.

Throughout Federalist 42, Madison characterizes the powers conferred upon the Federal government in the Constitution’s attempt to improve upon the Articles of Confederation as “obvious and essential” and speaking “their own propriety.” Given that even the smallest provisions within all constitutions “become important” over time, small errors like the one above had forced the Congress into choosing between usurping unappropriated powers and neglecting necessary duties. The members of the Constitutional Convention labored hard to make such choices unnecessary for the new Congress because they expected American statesmen to be as careful in their implementation of the text as they had been in the framing of it.

Unlike the pragmatists who have come to dominate American political thought and practice a century later, Madison realized that words relate to real things and that people behave accordingly. That truth applies to our nation “if we are to be one nation in any respect.” That truth applies to the Constitutional powers conferred to the federal government. And that truth applies to what happened the night of September 11, 2012.

Jay Carney has said that repeated calls to get to the bottom of what happened that night amount to “a conspiracy theory in search of a conspiracy” and that there is nothing here to see but D.C. business as usual (everyone writes talking points and preps Administration officials for Sunday morning talk shows). But that’s exactly the problem. The Obama Administration can be expected to continue to operate upon the basis that its words and deeds do not matter unless they make a difference. Unfortunately, they often do in unlooked for ways, as, for example, when meaningless “red line” talk regarding Syria turns into a real Russian annexation of Crimea.

The job of a House Select Committee, in retracing the steps of an obscure Benghazi email trail, must be to show the American public the heavy price that ruling class pragmatism has exacted on the government’s ability to carry out its constitutional responsibilities, starting with the four men who died for their country that night twenty months ago. Either way, the rest of the world at least won’t be fooled. As John Jay wrote in Federalist 4, “foreign nations will know and view it [our nation] exactly as it is; and they will act toward us accordingly.”

David Corbin is a Professor of Politics and Matthew Parks an Assistant Professor of Politics at The King’s College, New York City. They are co-authors of “Keeping Our Republic: Principles for a Political Reformation” (2011). You can follow their work on Twitter or Facebook.