So Senate Democrats held their all-night talkathon on global warming. Which might itself be considered a contribution to global warming, in the form of a massive emission of hot air. This all-night session took the outward form of legislative action—a filibuster, perhaps, or the kind of late-night session in which the Senate passed ObamaCare—but without any substance. As the New York Times report notes:

The members know that serious climate change legislation stands no chance of passage in this divided Congress, where many lawmakers in the Republican-majority House deny the science of human-caused global warming.

Except that this is not an honest description. House Republicans have nothing to do with it. The reason the Senate isn’t voting on global warming is because the Democrats lack support within their own caucus. You have to read down a few column inches to get the real story.

None of the four most vulnerable Democratic incumbent senators in the midterm elections—Mark Begich of Alaska, Kay Hagan of North Carolina, Mary L. Landrieu of Louisiana, and Mark Pryor of Arkansas—were to take part in Monday night’s event. Mr. Begich, Ms. Landrieu, and Mr. Pryor are from states where oil or gas production is a major part of the economy.

So then what was the session about? Well, partly it was a fundraiser.

California hedge fund billionaire Tom Steyer has pledged to spend up to $100 million in this year’s midterm elections to help elect candidates who support strengthened climate policy. His infusion has helped lead to the rise of what advocates call “climate candidates”—mainstream politicians who make climate change a central issue of their platform.

So in between warnings about those evil Koch brothers and the nefarious influence of money in politics, Democratic Senators are competing over who will get Tom Steyer’s millions.

But not all of the Democrats are up for re-election, so there’s more to it than that. Democrats are also attempting to shore up the support of their base by engaging in a ritual display to communicate how much they really, really care about global warming, even if they’re not going to do anything about it.

Or maybe the ritual display is the whole point.

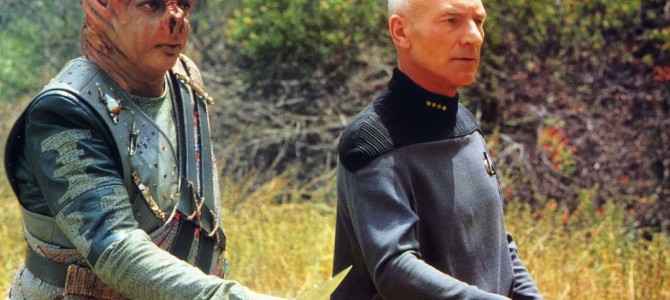

That possibility is suggested by a fascinating blog post from climate skeptic Anthony Watts on why skeptics have such a hard time being heard by global warming believers. He explains it by a long, insightful analogy to a classic episode of “Star Trek: The Next Generation.”

I like a good Star Trek reference as much as the next geek, and I really liked this one because “Darmok” is one of the best, most philosophically interesting episodes the franchise ever produced, and it’s high time someone applied its insights to our cultural debate.

Watts provides a longer plot summary, but I’ll shorten it to essentials. Captain Picard has brought the Enterprise to rendezvous with a spaceship from an “enigmatic” species who call themselves the “Children of Tama.” These Tamarians have attempted to communicate with the Federation, but their language is so unusual that it stumps even the “universal translator.” The Tamarian captain keeps repeating seemingly nonsensical phrases like “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra,” and “Shaka when the walls fell,” while Picard keeps saying things like “Would you be prepared to consider the creation of a mutual non-aggression pact between our two peoples, possibly leading to a trade agreement and cultural interchange?”

The Tamarian captain beams himself and Picard to the surface of an uninhabited planet, where they have to work together to fight off a mysterious beast. Picard then realizes that this is the meaning of “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra,” a reference to a Tamarian legend about two travelers who become friends after fighting a common enemy. The Children of Tama speak entirely in terms of images, metaphors, and allusions to stories and legends. “Imagery is everything to the Tamarians. It embodies their emotional states, their very thought processes. It’s how they communicate, and it’s how they think.” Picard uses this insight to crack the code of the Tamarian language and establish friendly relations with the Children of Tama.

This improbable premise is executed surprisingly well—the whole thing is worth watching, or you can skip to the central scene—and it offers all the philosophical ambition and humanist idealism that we love about Star Trek. So I was happy to see that it has enjoyed a long afterlife among fans, including the T-shirts.

It also provides an interesting way of understanding the clash between a method of thinking based on imagery and narrative, versus one based on facts and logic. Anthony Watts draws the conclusion:

I’m sure readers can see the parallels with climate change debate and its communications problems. One side repeatedly uses metaphors, imagery, and emotional attachments to convey the urgency of fighting the often invisible and fleeting “beast of the planet,” while the other side keeps asking pointed questions, tries to analyze what is being said and the situation, and tries to learn the language of the other side, even though it seems nonsensical. Neither side seems to get much from the other.

Watts hints that this can explain the global warming all-nighter in the Senate, and it’s not hard to see why. In a rant that almost justifies Joe Scarborough’s existence on television, he concludes that Senate Democrats are pretending that “This is 2014’s version of ‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.'” So the purpose wasn’t to accomplish anything or to communicate anything—not in the traditional sense. The purpose was to evoke an image, a metaphor, a narrative. The Senate Democrats are Children of Tama, and if you could translate their proceedings into Tamarian, it would be expressed something like this: “Mr. Smith, when he goes to Washington!”

Tamarian, after all, is the native language of politicians. They tend to talk in emotionally charged metaphors, images, and mythology—especially myths in which they cast themselves as the hero—which take precedence over facts and evidence.

This is an observation with wide application, in many different fields and on both sides of the aisle. I’m sure there are more than a few on the right whose commentary amounts to “Washington, at Valley Forge” or “Chamberlain, at Munich” and the like. On the whole, it’s a better choice of images and metaphors, but the method of thinking and communicating is the same. We all have to guard against the temptation of using narrative to replace evidence and logic.

But the cultural left has explicitly embraced this kind of narrative thinking, making it central to their worldview. I recently came across a rather amusing example: someone posted to Twitter a picture of a title page for the Critique of Pure Reason, an abstruse work by the 18th-century German philosopher Immanual Kant, stamped at the bottom with the following warning.

This book is a product of its time and does not reflect the same values as it would if it were written today. Parents might wish to discuss with their children how views on race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and interpersonal relations have changed since this book was written before allowing them to read this classic work.

Put aside for a moment the idea that any parent would be discussing Kant’s Critique with children. (It is written in famously impenetrable prose and is the type of book that should only be attempted by a trained professional with proper medical supervision.) This is a parody of modern political correctness, the presumption that the great and timeless works of Western Civilization must be filtered through the trendy “race, class, and gender” politics of the moment.

It is also deeply ironic, because the roots of this modern outlook lie within the pages of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. The essence of Kant’s argument—I’ll save you hundreds of pages of twisted, brain-melting grammar—is the idea that we cannot know reality as it really is, that everything we know comes to us filtered through a collection of mental categories which shape what we see to fit pre-set biases.

To be sure, Kant believed that these categories were inherent in our senses and were the same for everyone, so at least we’re all living in the same delusion. But the philosophers who followed Kant went to work on that assumption. They decided that our mental biases vary with our historical era (Hegel) or our economic relationships (Marx). The sociologists came back to report on exotic tribes who didn’t seem to share our “categories,” and personal subjectivists like Nietzsche claimed that our thinking is shaped by our emotional drives and particularly our “will to power.” By the late 20th century, all of this settled down, in the era of the “postmodernists” and “deconstructionists,” into the idea that our thoughts, our ideas, our very perception of reality is shaped by social power structures, particularly by divisions of “race, class, and gender”—and from this outlook modern political correctness was born.

Notice how this idea subordinates things like facts, evidence, and reason to pre-set narratives about racial oppression, Marxist economics, and sexism. To say that everything we think is determined not by objective reality but by our pre-existing biases is to say that there are no facts, only narrative. And this is precisely the conclusion embraced by the “deconstructionist” literary theorists. Which is to say that they have provided a philosophical justification for the Tamarian method of “narrative thinking.” The Children of Tama are actually the children of Kant.

This embrace of narrative thinking, and the contemporary obsession with narratives about race, class, and gender, explains many things about the left. Take the latest absurdity of political correctness, the “Ban Bossy” campaign. All of its many absurdities make sense if you stop trying to understand it in literal terms, as an attempt to prevent the use of an ordinary descriptive adjective, but see it instead as imagery and narrative about brave women standing up to the “patriarchy.” Translated into Tamarian, it might be, “I am woman, hear me roar.” Or perhaps, “Well behaved women seldom make history,” a slogan you have undoubtedly seen on a bumper sticker, especially if you live in a university town.

Chances are that you saw that bumper sticker on the back of a Prius pasted with a dozen other such slogans, each expressing some part of the imagery and narrative that drives our contemporary politics. These vehicles should be preserved as Rosetta Stones for some future Tamarian-to-English dictionary of the left.

This is the trend that has made education in the humanities increasingly incompatible with science and rational inquiry—a problem identified some years ago as a clash between two cultures speaking two different languages, each unable to understand the other. Which is exactly the situation projected in that Star Trek episode—except that in real life, those who use the language of the Children of Tama are incapable of building an industrial civilization, much less a starship. As one of my readers, Greg Gerig, put it to me, “imagine trying to communicate ‘the plasma conduits have fused, causing the antimatter differential overflow to spill into the Jeffries Tubes,’ via metaphor.” Scientific and technological achievement requires a language that is direct, literal, and precise.

The problem is that our contemporary, real-life Children of Tama have talked themselves into the belief that they are speaking on behalf of science and reason, and they pride themselves in rejecting their own culture’s ancient religious myths. In fact, that is one of their narratives. Expressed in Tamarian, it might be: “Galileo, and the Inquisition.” Which is why they are so unreachable by the skeptics: they don’t even know that they’re speaking a different language.

This particularly explains the visceral reaction against the “skeptical environmentalist” Bjorn Lomborg. His challenge to the environmentalist narrative seems relatively minor: he doesn’t even reject the idea that human activity is causing the globe to warm. Instead, he challenges the proposed solutions and sets out to systematically examine the costs of banning fossil fuels versus other ways to improve the human condition, based on facts and evidence. It’s that method that provokes the reaction. It’s not about challenging the specifics of the narrative. It’s the challenge he poses to the whole method of narrative thinking itself.

The global warming campaign, expressed in Tamarian, might be translated as: “Rachel Carson, and the Silent Spring.” Never mind that the dangers of DDT were exaggerated or invented, while its enormous benefits were ignored. That is just as irrelevant as whether there really were a Darmok and a Jalad, and whether they really went to Tanagra. In this method of thinking and communicating, all that is important is the narrative itself—in this case, a narrative about brave scientists standing up to stop industrial capitalism from “ravaging the earth.” Which itself is just a subset of a wider narrative we might express as: “Blake, and the dark Satanic mill.”

The left is free to indulge in narrative thinking, but it has its disadvantages. Precisely because it is metaphorical and driven more by vague resemblances than by exact truth, it is not taken and cannot be taken seriously as a guide to action.

By building a narrative in which they are the brave defenders of science, the left’s Children of Tama want to have it both ways: to allow themselves the flights of fancy of metaphorical thinking, while claiming the credibility of exact, literal truth. But reality trumps narrative, and they’re going to have to resign themselves to the persistence of these stubborn skeptics who keep challenging them on the rational basis of their theory.