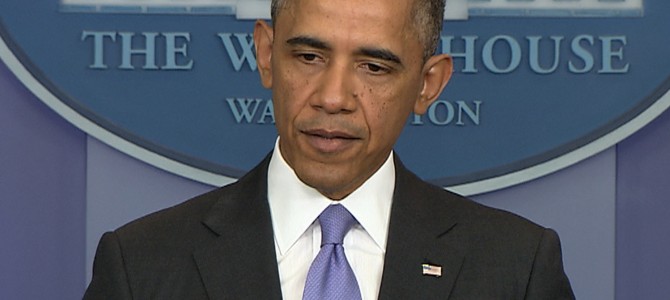

President Obama turned to the first play in the pragmatic progressive playbook this week in an attempt to redirect attention away from the failure of the Affordable Care Act. Rather than discuss a law that has as many devils as details, he dialed up “Hope and Change, 2008” with a cause so big joined to policies so vague that none could object: “the defining challenge of our time” is “making sure our economy works for every working American.”

This narrative is as old as American Progressivism itself (see Herbert Croly’s The Promise of American Life). It goes something like this. The Founders’ combination of political equality and economic liberty had run its course by the end of the 19th century because industrialization had undermined social mobility. The rich and poor lived completely separate lives, creating differences at the starting line in the race of life than made meaningless the legal right to compete with one another on equal terms. The Federal government, therefore, was duty bound to discriminate against advantages of talent and circumstance in an effort to more fully realize the promise of American democracy.

Of course, many a political and economic fortune would be made in the enterprise. But this is the rightful price that we pay for government action, which like the president’s health care reform, in his words, “can make an enormous difference in increasing opportunity and bolstering ladders into the middle class.”

But what of the opening premise of the president’s address, namely that economic inequality is more problematic now than ever? Has a century of progressive governance–and five years of the president’s own leadership–helped make the American people less rather than more equal, and all the while led us toward bankruptcy?

Consider, for example, the IMF’s latest debt statistics (go ahead, indulge yourself!), revealing the sobering realities of America’s march to insolvency. In 2008, the United States and the advanced economies of the Eurozone (combined) had almost identical levels of debt (73.3% and 70.3% of GDP, respectively). In the last five years, Europe, led by headline-grabbing basket cases like Ireland, Greece, Portugal, and Spain, has increased its debt rate by 25%–and the U.S. by 33%.

Still ahead for the U.S., of course: absorbing almost the entire Baby Boomer generation into Social Security and Medicare–and the fiscal impact of Obamacare, all the greater because of the massive growth in Medicaidenrollment it has inspired, even in states that have not chosen to expand eligibility.

All this will only add to the pressure for tax increases. Yet who and how much to tax? No worries, the IMF suggests that the top income tax rate in the United States is 10-25% lower than the rate likely to maximize income tax revenue. What is more interesting still is the fact that this calculation is based on the (IMF: “contentious to say the least”) assumption that “changes in welfare of those with the top incomes are not valued by policymakers.” Governments, in other words, want the money of the rich not happiness for the rich. Yet pursuing wealth redistribution through taxation has made neither rich nor poor happy.

We need not look far to see what the regime of a free and equal people looks like.

However much he is regarded as the “big government” founder today, Alexander Hamilton showed in Federalist 21 that his views on taxation were very far removed from the progressive ideology captured perfectly in the IMF’s calculations.

Under the Articles of Confederation, the national government had no taxing power at all. Instead, it issued requisitions to state governments, which were to raise the funds through local taxation. Although obliged by their own consent to supply the funds requested, the states very often did not. The results were nearly disastrous. Only the character and calming words of George Washington prevented soldiers from marching on Congress to demand their unpaid wages. Only the dextrous diplomacy of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, among others, prevented national insolvency when foreign loans came due.

As a result, nearly everyone agreed during the debate over the Constitution that the federal government needed a power to tax. But many sensibly feared that this necessary tool of government might become the tool of government oppression it had so recently been in the hands of the British Parliament. In response, Hamilton outlined principles of taxation for a free people that we would do well to heed today.

In the economic circumstances of his day (and before the income tax-authorizing 16th Amendment), Hamilton projected that most government revenue would come from taxes on consumption. These sorts of taxes had two noteworthy advantages. First, they were at least partially voluntary: “The amount to be contributed by each citizen will in a degree be at his own option, and can be regulated by an attention to his resources.” All consumption taxes, of course, can be avoided by saving, rather than spending money. But, as Hamilton notes, if the tax is confined to non-essential items, it can be voluntary in another way–anyone wishing to avoid the tax can simply avoid the items taxed.

Moreover, as Hamilton further argues, consumption taxes are naturally self-limiting: “If duties are too high, they lessen the consumption, the collection is eluded, and the product to the treasury is not so great as when they are confined within proper and moderate bounds. This forms a complete barrier against any material oppression of the citizens by taxes of this class, and is itself a natural limitation of the power of imposing them.” If you put a high tax on boats, some people will decide they don’t need a boat. Tax newspapers and the demand for magazines will rise.

There is a sense, of course, in which all taxes are self-limiting: people change their behavior when tax laws change. That’s why, for example, the revenue-maximizing top income tax rate calculated by the IMF is not 100 percent. But not all taxes are equally self-limiting. Those that are less obvious can only be minimized with careful attention. Those that touch necessary goods and income can only be minimized with pain. Insofar as the Progressive pragmatist recognizes these limits (and the track record of Democratic politicians on this point is not good), he does so reluctantly, with unmistakable moral judgment against the tax “dodger” and every effort to maximize the trouble and pain necessary to dodge. He naturally advocates an income tax system in which the government quietly keeps your first dollar.

On the other hand, Hamilton considers the (legal) tax “dodger” a guardian of liberty, protecting himself and his fellow citizens from oppression. He lauds consumption taxes precisely because they are so obvious and easily avoided.

Applied to present-day politics, Hamilton’s discussion of taxation would represent a complete rejection of the Administration’s attempt to persuade young Americans to enroll in Obamacare. Rather than lecture young Americans for choosing to pay a $95/month non-enrollment penalty in order to avoid a worse economic fate, Hamilton would praise their appropriate response to what amounts to an unfair, impractical, and unreasonable tax. Instead of reminding millenials of their vulnerability, Hamilton would remind the Administration that a government that asks too much of its citizenry makes itself vulnerable to just criticism.

Progressives expect equals to accept inequality as the starting point for what they deem moral and practical: for young people to embrace paying too much for health insurance so that others can pay too little. It should come as no surprise that millennials are not enrolling in Obamacare for the same reason they don’t fill their older model vehicles with super unleaded: they can’t afford to. Eventually we may all come to see such Progressive schemes as impractical. But of greater importance is that we all recognize the deeper, moral argument against Progressivism: that it is wrong to treat equals unequally–especially in the name of equality.

David Corbin is a Professor of Politics and Matthew Parks an Assistant Professor of Politics at The King’s College, New York City. They are co-authors of “Keeping Our Republic: Principles for a Political Reformation” (2011). You can follow their work on Twitter orFacebook.