Most people know about the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO’s) Article 5 pledge of collective defense: An attack on a NATO member is considered an attack on all members. Undergirding Article 5 is the promise all NATO members made to maintain defense spending at 2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

The idea behind the 2 percent rule is simple: No NATO member can come anywhere near America’s $700 billion Pentagon budget, but America has a much larger economy than the other NATO members do. By requiring each NATO member to contribute according to the size of their respective economies, the alliance ensures every country contributes its “fair share.”

This rule attempts to cut down on free riders. Germany, for example, might think that given America’s commitment to defend them—and a never-higher American defense budget, surpassing U.S. defense spending even at the height of the Cold War in real (inflation-adjusted) terms—allows Germany’s politicians to sit back and let America do all the work.

But the rule is being ignored. Right now, countries in the NATO alliance are largely not meeting their obligations—and there’s no indication they plan to do so.

In 2017, America spent 3.58 percent of GDP on defense. Germany spent 1.22 percent of GDP, Belgium spent 0.91 percent, Italy spent 1.13, Spain spent 0.92, and the Czech Republic spent 1.07 percent. France, meanwhile, spent a relatively better 1.79 percent of GDP on its defense tab. Our neighbor to the north, Canada, controls huge amounts of relatively unpopulated territory with oodles of natural resources, but only spends 1.31 percent of GDP on defense.

Of NATO’s 28 members that existed in the full year of 2017, the only five countries (aside from America) that met their 2 percent obligation were the United Kingdom., Romania, Poland, Greece, and Estonia. Even this list requires an asterisk, as Greece meeting its target has much to do with that country’s beleaguered economy shrinking in the last decade.

None of this is a new development. After the Trump administration’s focus on this issue, these numbers are actually a slight improvement from years past. That’s why the Trump administration continues to push the issue. Advocating for greater burden-sharing, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo just met with other NATO members’ foreign ministers in Brussels. The Trump administration would like each NATO member to hit the 2 percent target by 2024. But there is notable pushback.

In but one example, Germany—Europe’s largest economy—plans to increase defense spending to only 1.25 percent of GDP by 2021. That’s a real problem. Germany’s economy is about 2.5 times the size of Russia’s, the country that is the chief justification for NATO’s continued existence. But Russia spends almost $80 billion on defense, while Germany spends about $45 billion.

And it isn’t just about dollars spent. It’s easy to hire soldiers or bureaucrats, but NATO also requires that 20 percent of military spending go to heavy equipment. Germany again is the poster boy for why the latter part of this “2 and 20” rule exists. Right now, due to a technology problem and the lack of missiles, only four of Germany’s 128 Eurofighter jets are combat-ready.

America benefits from capable partners, not wealthy client-states dependent on our good graces. Article 5’s commitment to common defense means nothing if other NATO members aren’t making, or actively trying to make, their contributions to the club.

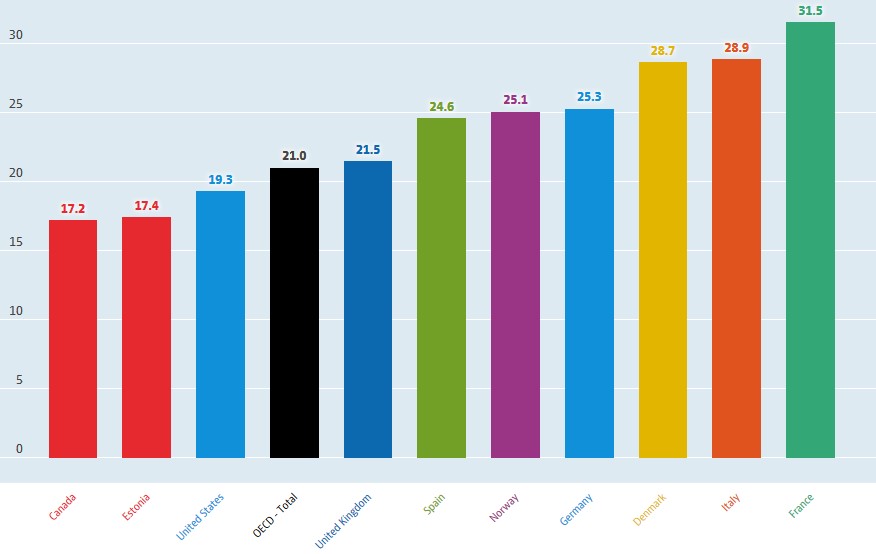

When America picks up the tab Germany’s defense, wealthy Germany gets to spend the money elsewhere. Better yet for Germany, spending less on defense helps it to have a balanced budget. But these European governments aren’t running frugal democratic-republics. On the contrary, many NATO members are spendthrift welfare states. In other words, the United States, through NATO, subsidizes Europe’s massive safety net.

Public social (welfare) spending of select NATO members, percent of GDP, 2016 or latest available. Source: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

That must stop. Whether or not one thinks Europe’s welfare state is advantageous to society at large is not the issue. Very simply, U.S. taxpayers shouldn’t be subsidizing European largess. America’s budget deficit—the amount our federal government spends in excess of what it takes in per year—is fast approaching $1 trillion, with no end in sight. This level of overspending is unprecedented outside of a recession.

It might be a state issue, but many of America’s roads, bridges, and canals are in disrepair. And America needs a new program of technical and trades education to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century. All this will cost even more money.

On the campaign trail, Trump called NATO “obsolete.” That comment received a good deal of pushback from the halls of power and cable television prognosticators. Yet because NATO members refuse to uphold their end of the bargain, then-candidate Trump was, and is, right.

As the major power in existing alliances, America should be providing support to regional allies, but we should not act as wealthy Europe’s first-responder. Our rich European allies must become partners with high-end capabilities that defend their own neighborhoods. Allowing NATO allies to continue to drain precious resources, which should be used to deter greater threats to American security, is not acceptable.