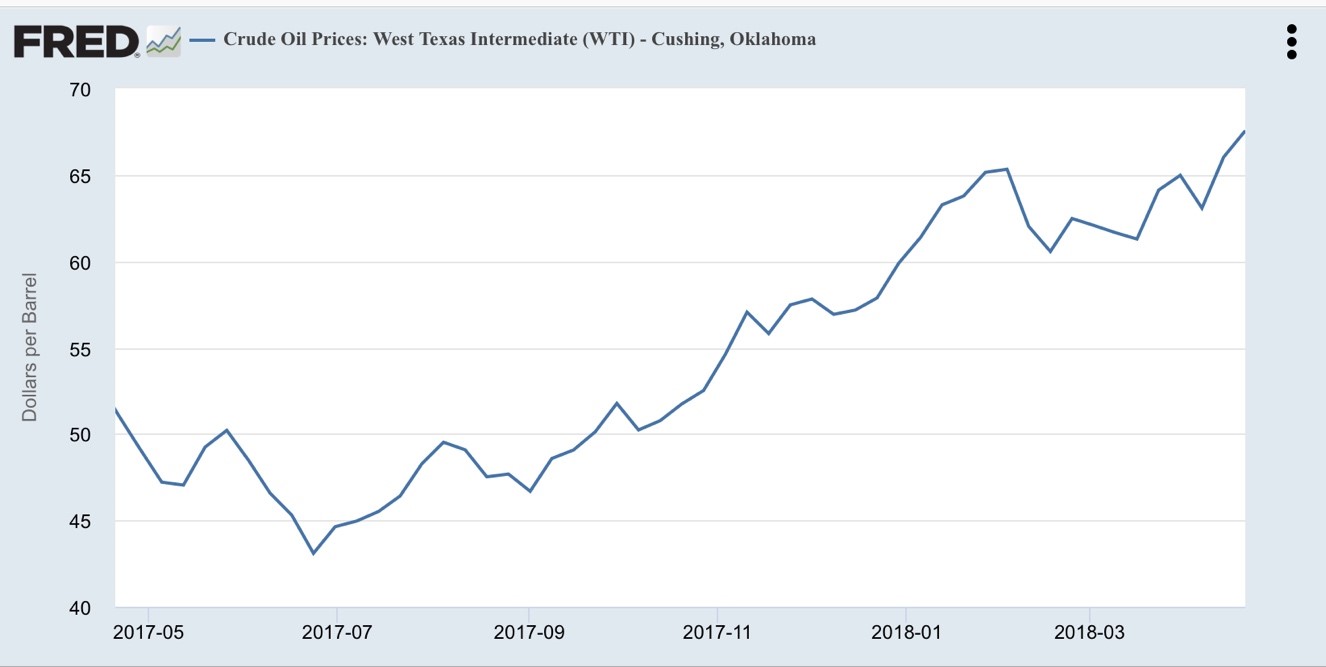

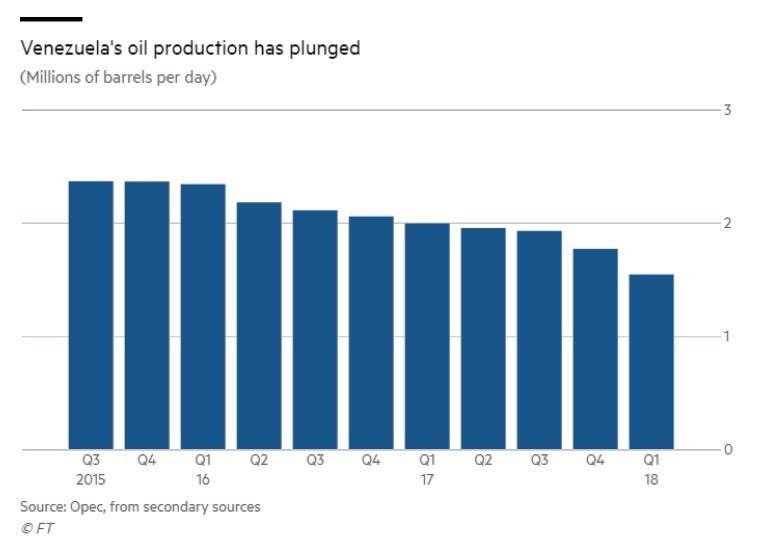

News media have been publishing frequent reports about why Venezuela is doing so badly. Usually they cite falling oil prices. But since September 2017, oil prices have been rising. How much has the Venezuelan economy improved? How much have their oil exports increased? The short answers are, “The economy has gotten worse” and “Oil exports have continued to decline.”

The BBC weighed in with this screaming headline: “Venezuela’s decline fuelled by plunging oil prices.” CNBC offered this succinct analysis:

Oil accounts for 95 percent of Venezuela’s export earnings, and combined with gas, it’s 25 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. As the price of oil hits a four-year low at $70 per barrel, the OPEC nation’s oil-dependent economy is set to implode, experts say, bringing deeper political instability and chaos to the world’s 10th-largest oil exporter.

At least the Financial Times got it a bit right. Writing about Halliburton’s decision to write off the remaining $312 million of their investment in that country, it reported “Venezuela’s financial crisis and mismanagement have wreaked havoc in the country’s energy industry. The result is a downward spiral, in which weak revenues damage oil production, which then weakens revenues further.”

But there’s a major contradiction in all these arguments. For the last year oil prices have been rising.

U.S. Energy Information Administration, Crude Oil Prices: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) – Cushing, Oklahoma [DCOILWTICO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Higher oil prices should mean more export revenue for Venezuela. In addition, standard economic theory says a higher price should increase the quantity supplied.

Venezuela should be selling more oil at a higher price, bringing in much more revenue. So why haven’t conditions improved? Here’s part of the answer:

The Actual Source of the Problems Is Socialism

There are two basic causes of Venezuela’s problems. The first is socialism. When the government owns the means of production, they are effectively managing businesses. And government does a terrible job of this.

It’s pretty clear that Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro administration can’t even keep oil fields pumping. And no major oil company will explore in Venezuela because they know any new oil pools they discover will be immediately confiscated by the government.

Economists often talk about the “calculation problem” as the source of socialist economies’ woes. The idea is that the government must know the tastes, preferences, and incomes of every consumer in the economy, as well as keep track of consumers’ changing attitudes. When a new piece of technology is produced, suddenly people are able to buy something that wasn’t available before. Their preferences are likely to change.

That’s half the calculation problem. The other half is matching consumer demand with production. Goods and services must be produced at a cost low enough that buyers can afford them. A second fact about government is that most are not very good at being efficient.

Let’s think about this in practical terms. Most people have been inside a U.S. supermarket. According to the Food Marketing Institute, the average supermarket carries 38,900 items. Imagine having to figure out how much of each item consumers would buy at a given price. Once you’ve done that, you need to produce that quantity at a cost that’s at least a little less than the price. Good luck.

Venezuela’s second mistake was imposing price controls. That’s why you routinely see pictures of supermarkets with empty shelves. Rather than diving into economic theory, let’s look at an example to see how price controls create shortages.

Why Shortages Exist

Consider the market for Fuji apples. At $2.79 per pound, the supermarket manager is pretty sure they can sell most, if not all, the apples before they go bad. Consumers can buy all the Fuji apples they want (and can afford) at that price. This market is in equilibrium. At this price, the quantity of apples consumers want to buy will be the same as the quantity the supermarket wants to sell.

Now the government decides Fuji apples are good for your health. Government officials believe the current price is too high, so some people who need apples can’t afford them. The government passes a law saying the highest price a supermarket can charge for Fuji is $2.

Two problems will happen. First, when the price of Fuji apples falls, some consumers who had been buying Honeycrisp apples will switch to Fuji. Naturally this also applies to other apple varieties. Some others who had been buying Bosc pears will decide Fujis are a better deal. The result? Consumers will want to buy more Fujis.

What about the supermarket? The manager quickly figures out that his store’s profit margin on Fujis is lower than other apples and other fruit generally. The manager will reduce the quantity of Fujis for sale, while increasing the quantities of other fruits. In other words, the quantity available for sale falls.

Consumers want to buy more. The seller wants to sell less. This creates a true shortage. Buyers who get to the market immediately after Fujis are restocked will buy up most of them, more than they can consume. Those apples will be sold in a black market. The price will be higher than $2.79. And buyers who arrive at the store later will find the Fuji bin empty.

This is universally true. A major function of prices in any market is to get supply to equal demand. Economists call this price rationing. Once price is no longer allowed to ration a good, some other mechanism must be put in place.

In the 1970s the U.S. government put a ceiling price on gasoline. There were long lines with people waiting for hours to buy gasoline. This is rationing by queueing. Those at the end of the line sometimes got no fuel at all. Some gas stations limited purchases to, say, 10 gallons per customer. One of my classmates in the economics program at Stanford had the bright idea of hiring undergraduates to sit in people’s cars, charging the driver for the service. He made a mint. And the rest of us kicked ourselves for not thinking of it.

An entrepreneur in Ohio came up with an alternative rationing scheme. His customers could buy all the gas they wanted, but they first had to buy a stuffed teddy bear for $25. Naturally, the government told him to cut it out.

This Applies to Shortages in Venezuela

In Venezuela, the population is literally starving while government employees, the military, the police, and their pals remain well fed. But there’s another seeming contradiction. Despite price controls, inflation is raging. How can that be? With prices of goods and services controlled by the government, how can the average price level be rising rapidly?

Milton Friedman once famously said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Today we know short-run shocks to the economy can create temporary bursts of inflation. But over the long run, allowing for economic growth, Friedman and Anna Schwartz were pretty much correct.

But one event is always caused by excessive growth in the money supply: hyperinflation. Inflation is an increase in the average price of all goods and services over some period of time. The United States, like most developed economies, has set an inflation target of 2 percent per year. (There are good reasons for this, but the explanation would take us too far afield.)

In a hyperinflation, the inflation rate is at least 50 percent per month. Simple arithmetic says that’s 600 percent per year (50 percent per month times 12 months). A more nuanced calculation takes compounding into account and puts the rate at nearly 1,300 percent per year. The price level will increase by a multiple of 13 during a single year! If that applies to, say, a loaf of bread that cost 1 Bolivar at the beginning of the year, the same loaf would cost 13 Bolivars by the end of the year.

Hyperinflations are always, 100 percent of the time, caused by excessive growth in the money supply. This often happens when a government has run up a huge debt from persistent budget deficits and is suddenly unable to borrow any more. The government will then print money to finance its ongoing deficit, and consequently the country sometimes goes through a hyperinflation.

To put it simply, inflation is too much money chasing too few goods. Hyperinflation is way, way too much money chasing almost no goods.

The Unofficial Monitor of Hyperinflations

Steve Hanke is a professor of applied economics at Johns Hopkins University and a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. Over the years he has created the “Troubled Currencies Project” to track economies that are either experiencing a hyperinflation or seem to be headed in that direction. Here’s what he says about Venezuela:

Venezuela’s inflation has officially become the 57th official, verified episode of hyperinflation and been added to the Hanke-Krus World Hyperinflation Table, which is printed in the authoritative Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History (2013). An episode of hyperinflation occurs when the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50 percent for 30 consecutive days. Venezuela’s monthly inflation rate first exceeded 50 percent on November 3rd and continues to do so, sitting at 131 percent as of December 11, 2016.

Here are the inevitable results:

How Does a Hyperinflation End?

In a word, badly. When Zimbabwe was in the throes of its hyperinflation, their government simply did away with their domestic currency and started using the U.S. dollar. Effectively, they put the Unite States in charge of their monetary policy!

The German hyperinflation after World War I did not end so nicely. Economic historians cite it as one of the factors that led to the rise of Adolf Hitler.

What will happen in Venezuela? Right now, for reasons only Maduro understands, the government seems bent on starving a large part of the population to death. While we’re all horrified at the mere thought of that being a government policy, it’s hard to see it any other way.

Besides the horrific humanitarian implications, there would be consequences for the economy. Producing goods and services takes labor. Reducing the size of the labor force will, at least temporarily, reduce the quantities of goods and services available, which will make the shortages even worse. This is the worst positive feedback loop imaginable. (For anyone who is curious, here’s a link to my blog post that explains Hanke’s methodology in detail.)

Falling oil prices are not the problem in Venezuela. The problem is socialism, price controls, and a money supply spiraling out of control. It’s absolutely tragic. But it’s also the usual outcome. As the late British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher put it, “Socialism is a great system until you run out of other people’s money to spend.”