Various societies crucified condemned victims from the at least the fifth century BC to the fourth century AD. Herodotus in “History” relates how the Athenians hanged Persian viceroy Artayctes by nailing him to boards, c. 479 BC.

After capturing the Phoenician city Tyre in 332 BC, Alexander the Great crucified 2,000 survivors along the Mediterranean coast, according to Quintus Curtius Rufus in his “Life of Alexander.” The victor of the Third Servile War in 71 BC, Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus crucified 6,000 defeated gladiators and slaves, who had been led by Spartacus, as reported by Appian in “Civil Wars.”

Judeans also suffered this torment, as Josephus reported in “War” and “Antiquities.” Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes attacked Jerusalem in 167 BC (1 Maccabees 1:20-25 and 2 Maccabees 5:11-14), butchering tens of thousands of traditional Jews in 167 BC, many of whom were crucified, according to “Antiquities.”

Exacting revenge for rebellion, Hasmonian king Alexander Jannaeus in 88 BC crucified 800 Pharisee rebels while they witnessed the slaughter of their wives and children. “War” describes Syrian governor Publius Quinctilius Varus (possibly Quirinius in Luke 2:2) crucifying 2,600 to quell unrest following Herod’s death, and Gessius Flores in AD 66 scourged and crucified 3,600. Titus Flavius Caesar tortured and crucified hundreds of scavengers outside Jerusalem over several days four years later, as Josephus relates in “War.”

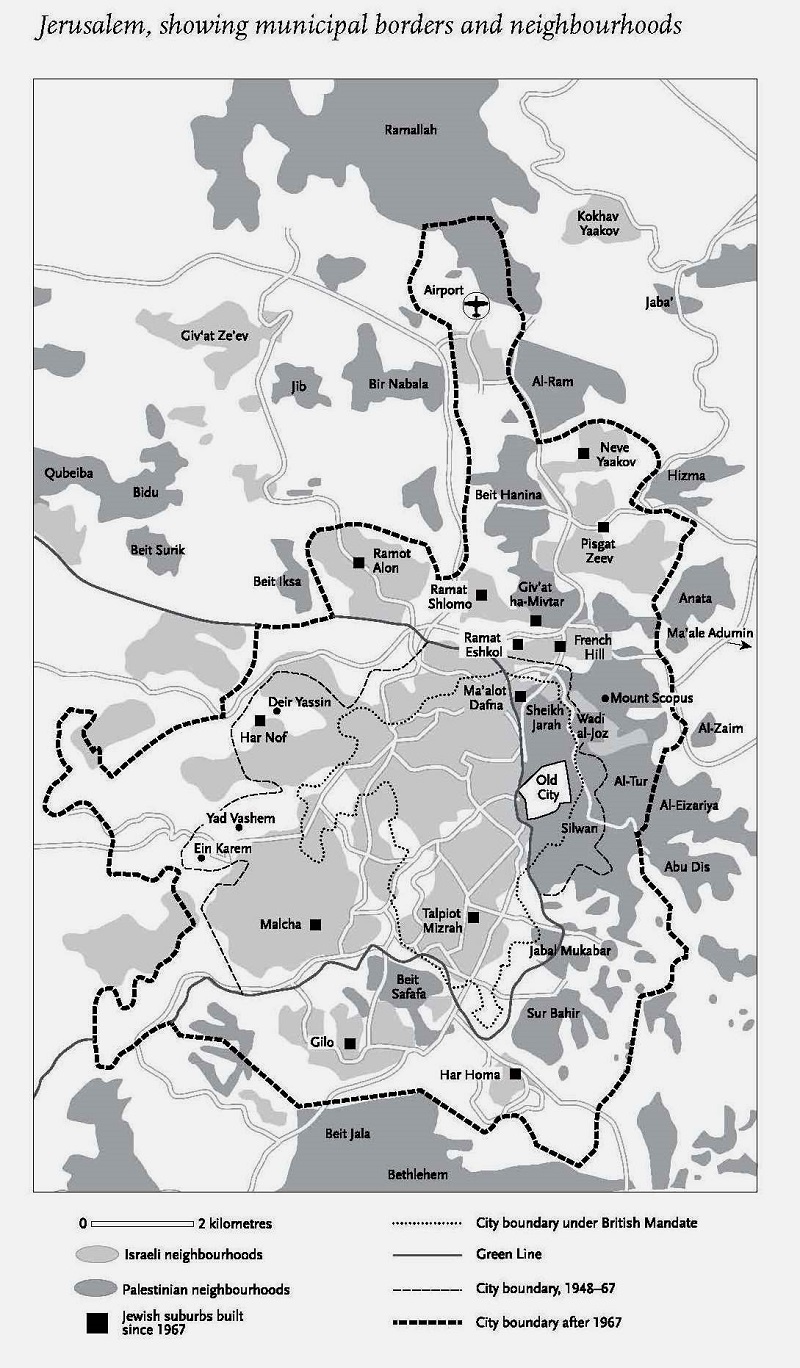

Yet despite literary accounts of hanging persons from a gibbet until their expiration, the paucity of archaeological evidence to verify these executions renders details uncertain. Half-a-century ago this June, archaeologists discovered four tombs hewn into the limestone near Giv‘at ha-Mivtar, about two miles north of the Old City in Jerusalem. Based on the pottery found therein by Vasileios Tzapheres, these burial sites date from the second temple period.

The four tombs held 15 limestone ossuaries, or bone boxes, containing a total of 35 skeletons belonging to 11 adult males, 12 adult females, and 12 children. In Judea, a person’s corpse would be placed on a ledge in a cave, and after the flesh rotted off, the bones were deposited in an ossuary for reburial. According to Nico Haas, three children had died from starvation, one adult male and one child had been killed by a weapon, and one adult male was executed by crucifixion.

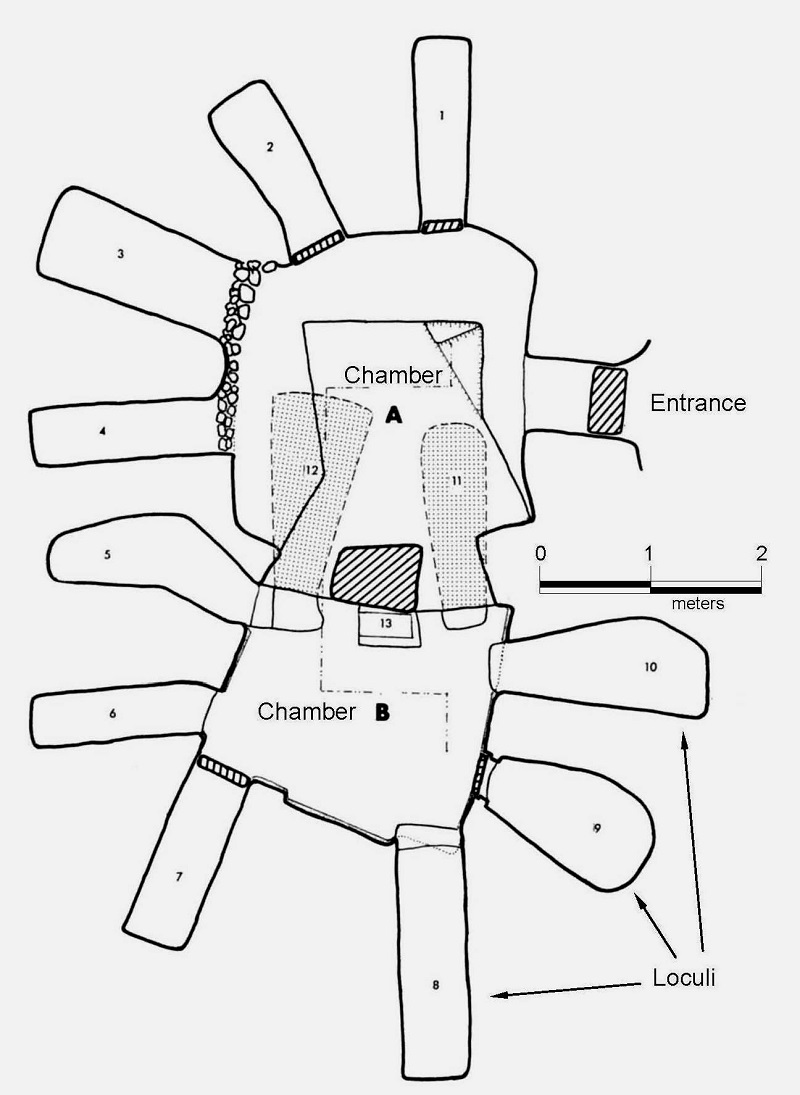

The first tomb, from the first century AD, had two chambers labeled A and B, each with several loculi or niches. At the time of discovery, the ossuaries there were located in chamber B and the ninth loculus. Of particular interest was the fourth ossuary, found in chamber B. This box capped with a flat lid contained skeletons of one adult man and one child of indeterminate sex. An iron nail through the right heel bone showed that the man had been crucified. Due to ultra-Orthodox requirements, only four weeks of forensic analysis was permitted before reburial.

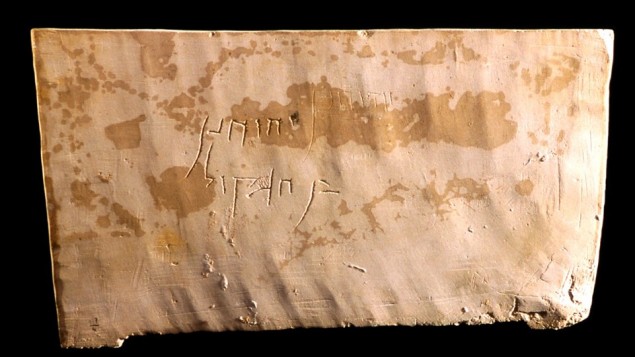

The ossuary that included the crucified man’s bones measured 22.4 inches by 13.4 inches and was topped by a flat unadorned lid. One side featured an inscription: “yhwḥann / yhwḥann bn ḥgqwl,” suggesting that the two skeletons belonged to father and son. The child was between three and four years old at death.

The remains of the crucified man, Jehohanan, indicated that he died between 24 and 26 years of age, about 65.7 inches tall with robust limbs, no diseased bones, and all teeth present without signs of decay. His long narrow skull showed a cleft palate and bilateral asymmetry with the left side of the cranium larger than the right, perhaps resulting from prenatal malnourishment. Both calcanean (heel) bones had been pierced.

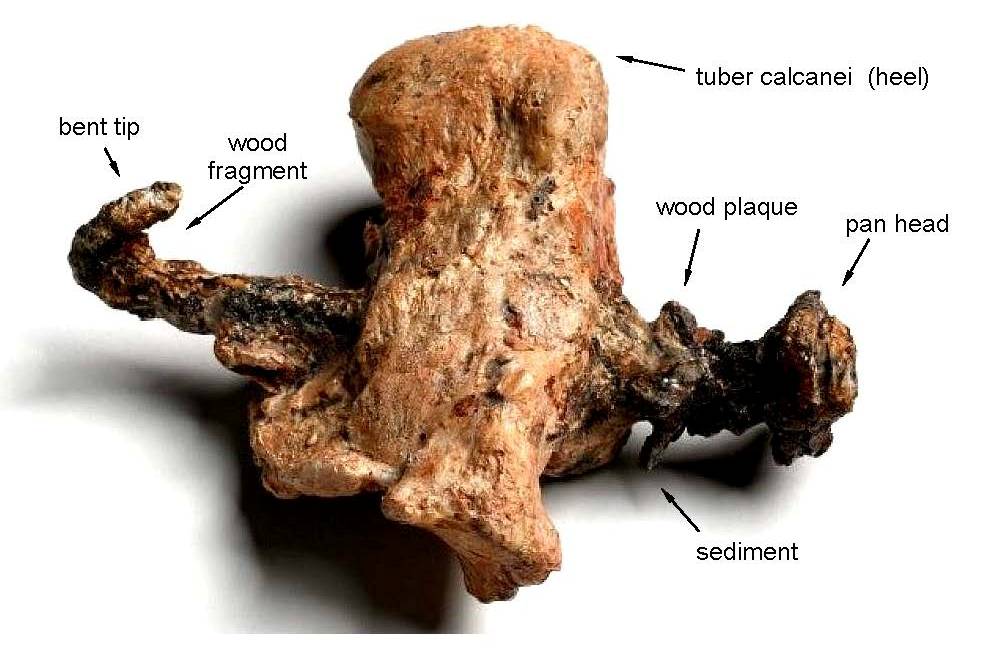

An iron nail 4.5 inches long penetrated through the right calcaneus. The rusty nail had remained embedded because the tip had been bent back, perhaps from striking a knot when being hammered into the stake that fastened the feet thereon.

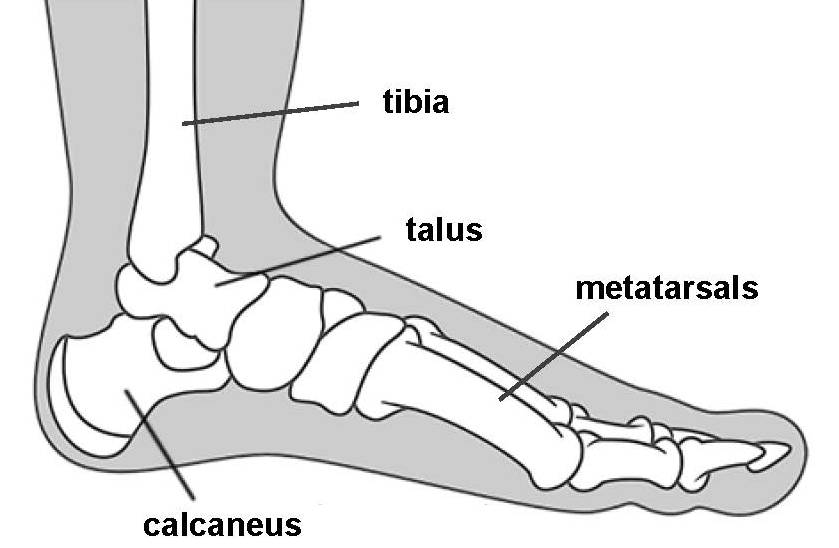

The accompanying illustration shows the arrangement of human foot bones with the talus (ankle bone) joining the calcaneus to the tibia (shin bone). The skeletal right tibia and the left tibia and fibula were broken, which Haas presumed had been to hasten death (John 19:32).

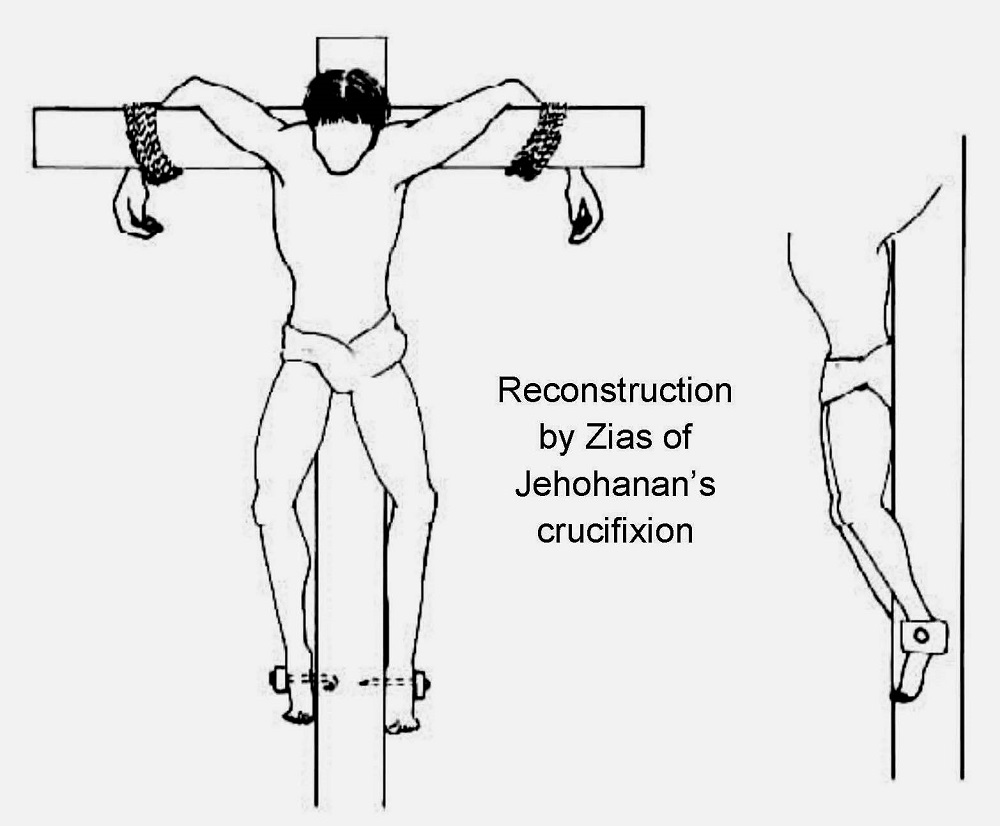

A pan head tops the iron nail, coated by a crust. To prevent the victim from pulling his foot out, the nail passed through a wood plate before penetrating the ankle and into the stake. This was evident by the residue plaque between the head and the calcaneus. Haas determined the plaque as composed of acacia or pistacia and the fragment at the tip as olive, and surmised that both of Jehohanan’s ankles had been fastened to an olive stake by the nail and his arms nailed to a crossbeam.

However, reappraisal of the remains by Joseph Zias concluded that the nail lacked sufficient length to fasten both ankles together, so these were separately fixed on either side of the stake. The plate near the nail head was olive, while the amount of wood fragment near the tip didn’t permit identification. Zias also found that the leg bones had been broken post-mortem. The absence of lacerations on the arm and wrist bones meant the arms had been tied to a crossbeam, as indicated by his sketch.

Romans typically left the condemned wretches to decompose in situ on the gibbet, as noted by the Latin poet Horace in “Epistle” admonishing slaves against ingratitude so as not to “hang on a cross and feed crows.” Given that the cruelty of crucifixion applied primarily to slaves, rebels, and captives, wouldn’t Jehohanan’s body have been discarded, rather than available for archaeological discovery?

Perhaps. However, hewn tombs could only be afforded by prosperous families, and Jehohanan’s bones suggested an ample diet and absence of structural trauma from injury or manual labor. Moreover, Jewish custom in Deuteronomy 21:23 and affirmed in “War” requires the executed to be buried before nightfall, for which “War” presents an example. Roman administration may have ordinarily permitted such burial customs in Judea to ensure tranquility. Nonetheless, presuming that Jehohanan’s cadaver would be treated properly by relatives of means does not strain credulity.

From these examinations, historians can gather some information regarding the most famous crucifixion—that of Jesus of Nazareth by Pontius Pilate, probably in AD 33. That this gruesome practice occurred cannot be doubted, as archaeological evidence (however meager) confirms the ancient literature. In addition, while burial of the hanged bodies might be uncommon, the case of Jehohanan indicates internment could occur for someone who received the attention of others who could intervene.

The synoptic gospels agree that Joseph of Arimathea petitioned (and probably bribed) Pilate to release Jesus’ corpse (Matthew 27:57-60, Mark 15:43-46, Luke 23:50-53). With less flourish, the Apostle Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 15:4 and is quoted in Acts 13:29 to affirm that Jesus had been buried. That forms the basis of the Christian assertion of an empty tomb for their messiah from which to subsequently reemerge.