With less than a month to go before Alabama’s special election to fill the Senate seat left vacant by Attorney General Jeff Sessions, Republican candidate Roy Moore refuses to quit the race amid fallout over credible allegations of sexual assault dating from the 1970s, including that he initiated a sexual encounter with a 14-year-old girl when he was 32.

Some polls still show Moore leading his Democratic opponent Doug Jones, while a poll conducted by the National Republican Senate Committee earlier this week shows Moore trailing Jones by 12 points.

Senate Republicans are calling on Moore to withdraw from the race, saying he’s “unfit to serve” and threatening not to seat him if he’s elected, but Moore isn’t backing down. His campaign has called the allegations a politically motivated “witch hunt” and Moore has vowed to stay in the race, which means there’s still a chance the people of Alabama might elect him to the U.S. Senate.

All of this could have been avoided if we’d just repealed the Seventeenth Amendment.

Good Reasons for Allowing States to Elect Senators

The Seventeenth Amendment says U.S. senators must be elected by popular vote, instead of by state legislatures. Adopted in 1913 during the height of the Progressive Era, the amendment supersedes the provisions in the Constitution that required senators to be elected by state legislatures.

The idea that state legislatures would elect senators might seem odd nowadays, but creating some distance between the popular vote and the election of senators was crucial to the Founders’ grand design for the republic. The original idea, spelled out in The Federalist Papers, was that the people would be represented in the House of Representatives and the states would be represented in the Senate. Seats in the House were therefore apportioned according to population while every state, no matter how large its populace, got two seats in the Senate.

The larger concept behind this difference was that Congress needed to be both national and federal in order to reflect not just the sovereignty of the people but also the sovereignty of the states against the federal government. In Federalist No. 62, James Madison explained that Congress shouldn’t pass laws “without the concurrence, first, of a majority of the people, and then of a majority of the states.”

Besides tempering the passions of the electorate, empowering state legislatures to elect senators was meant to protect the states from the encroachments of the federal government. The tension was (and still is) between the dual sovereignty of the national government and the states. Writing in Federalist No. 39, Madison explains that while the House of Representatives is national because it “will derive its powers from the people of America,” the Senate “will derive its powers from the States, as political and coequal societies.” We’ve lost much of this today, but the jurisdiction of the federal government, wrote Madison, “extends to certain enumerated objects only, and leaves to the several States a residuary and inviolable sovereignty over all other objects.”

A Wave of Populism Gave Us the 17th Amendment

The Founders were nearly unanimous in this view of dual sovereignty and why it necessitated the Senate be elected by state legislatures. Only one member of the Constitutional Convention, James Wilson, supported electing senators by popular vote. But it wasn’t long before the idea gained traction. The Seventeenth Amendment was first submitted to the Senate in 1826, amid the country’s first real wave of populism, which culminated in the election of President Andrew Jackson in 1828.

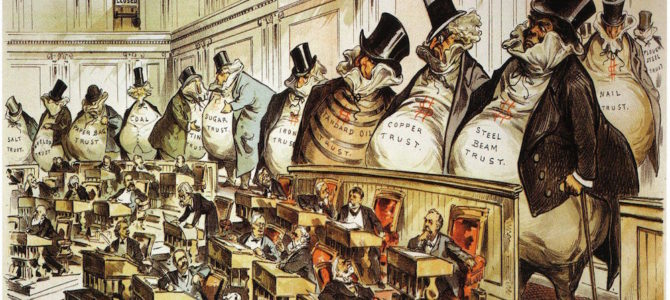

By the time the next big wave of populism swept America in the late nineteenth century, calls to amend the Constitution and elect senators by popular vote had grown much louder. When the House passed a joint resolution proposing an amendment for the election of senators in 1911, it was part of a populist anti-corruption movement that included among its prominent supporters William Jennings Bryan, who as secretary of state certified the amendment after 36 states ratified it in May 1913.

The chief argument in favor of it was that Gilded Age industrial monopolies like Standard Oil exerted too much control over state legislatures, and hence too much control over the U.S. Senate. To be sure, late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century state legislatures were notoriously corrupt. At almost every level of government, rank corruption and machine politics was the norm. President Benjamin Harrison, elected in 1888, said upon learning that much of his support had been bought, “I could not name my own cabinet. They had sold out every position in the cabinet to pay the expenses.” In 1897, Mark Twain famously quipped, “It could probably be shown by facts and figures that there is no distinctly native criminal class except Congress.”

The populist fervor during this time shouldn’t be overstated, though. Ironically, the Seventeenth Amendment, which was purportedly about giving the people a greater voice in government, was passed seven years before the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave half the country (women) the right to vote. And, of course, Jim Crow laws in the South continued to suppress the votes of blacks and poor whites.

The 17th Amendment Hasn’t Been a Huge Success

But we’re no longer living in the era of late-nineteenth-century industrial monopolies. While government corruption was in many ways codified by the New Deal, we also no longer face the same kind of rank corruption as that in the Gilded Age.

It’s time, in other words, to reconsider the Seventeenth Amendment. Given our current wave of populism, it might be wise to reintroduce some of those old ideas about federalism, and temper the passions of the electorate by letting states, not the people, elect senators.

After all, it’s not like the Seventeenth Amendment has reformed the Senate into a serious deliberative body that responds to the wishes of the people. Were it not for the Seventeenth Amendment, we might have never had Strom Thurmond hang around the Senate for 48 years, serving until he was 100 years old. We might not have had former KKK Grand Wizard Robert Byrd serve for 51 years. We might have even escaped the scurrilous and corrupt Theodore G. Bilbo of Mississippi, also a prominent Klansman, who once said “Once a Ku Klux, always a Ku Klux.” And who knows, after Chappaquiddick, the Massachusetts legislature might have picked someone other than Ted Kennedy to represent the state.

Of course, maybe we would have ended up with all those guys anyway. But there’s a decent chance at least some of them eventually would have been voted out by their state legislatures. Just like there’s a decent chance, were it not for the Seventeenth Amendment, we might not be facing the prospect of Senator Roy Moore of Alabama.