In the 15 years since I became a mother, Easter has meant several things: special church services, new spring dresses, dye-stained eggs, dye-stained fingers, Easter candy. Most memorably, it has also always meant a trip to Papa and Nanny’s house.

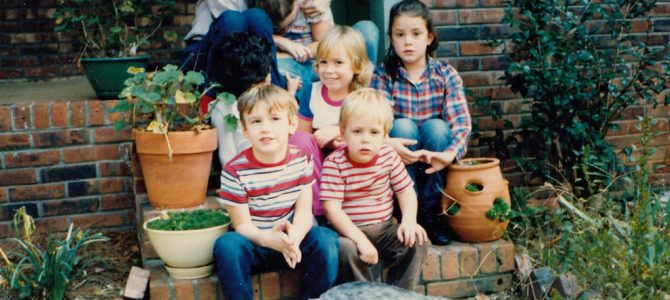

Easter and Thanksgiving have always been the two holidays when my husband’s whole family gets together. Twice a year, everybody gathers at his parents’ Virginia home for a weekend of food, games, music, and general tomfoolery. My husband and I were the first to bring a baby to the party in 2002, and more came along in subsequent years. Our last Easter gathering saw six grandkids hunting eggs on my in-laws’ lush green lawn, surrounded by an acre of forest.

Papa and Nanny’s house—an insignificant spot on the map to anyone else—holds a near-magical charm for my children. The first glimpse of the mailbox elicits squeals of delight after our four-hour drive. Just beyond the front woods lies the little lawn, always soft underfoot, edged by a small pond my father-in-law built years ago. Inside, the open living area boasts cheerful decorations and instant memories of family games, movie nights, and tiny grandkids dancing to bluegrass tunes.

Goodbye to the House in the Woods

Last year, my father-in-law retired from his 20-year teaching job at the local university. That spring, Papa and Nanny broke the news that they planned to move “back home” for their retirement years—to the Tennessee mountains where they’d raised their three children. For them, it meant a return to familiar places, old friends, and family who could care for them as they grow older. But my kids saw only one thing: Papa and Nanny were leaving their magical house in the woods, the only home in which they (or I) had ever known them.

Last month, before the house went up for sale, we held our Easter gathering a little early. The forest was still leafless, but the weather was warm. There was the usual fun: cornhole games on the lawn, an egg hunt, a cousin talent show. Nanny baked two cakes, and Aunt Jen brought crafts for the kids. Beneath the frivolity, though, my children were continually conscious that something was different. This was our last visit to Papa and Nanny’s house. For this little spot that had been the backdrop for so many childhood memories, it was goodbye.

It’s a mark of how stable and happy my kids’ lives have been that this event held so much weight. In a world where babies are murdered by sarin gas and bombs rip through Palm Sunday services, it seems the ultimate privilege to mourn the loss of a grandparents’ house. Yet mourn they did. We had several tearful talks surrounding our final visit. “It’s always been Papa and Nanny themselves who made the house special,” we told them. “Remember that you’re not losing them!”

All Human Lives Bear Losses

My kids aren’t just grieving for a house, though; they’re grieving for the brevity of life. With each passing day, they get closer to the time when they will lose Papa and Nanny. In fact, my in-laws’ decision to move was in many ways a preparation for, and an acknowledgement of, this later season of their lives. This small goodbye foreshadows that future one, reminding us that nothing in this world lasts forever.

My children themselves are living evidence of life’s transience. Those tiny toddlers who twirled to the music in Nanny’s living room are gone, replaced by young ladies with braces and driver’s permits. The days of jumping into Papa’s giant pile of autumn leaves have ended, not just because he’s moving away, but because they’ve become too old. Children grow, their childhoods flying away forever. Parents age. We all are in a slow but dreadfully sure process of losing one another. In a tiny way, it’s the same tragedy that daily plays itself out everywhere around the world: the tragedy of human mortality.

My 13-year-old in particular hates the changes wrought by the inevitable march of time. On our last day at my in-laws’ house, she walked around the property taking photos of every nook and cranny, desperate not to lose anything from her memory. To varying degrees, we’re all like that. Despite all evidence, we still treat death and change as intruding strangers, a violation of the natural order. We chafe against the uncertainty and instability of the world. We get nostalgic for the way things used to be. We want to live forever.

“Most people, if they had really learned to look into their own hearts,” C.S. Lewis observed in “Mere Christianity,” “would know that they do want, and want acutely, something that cannot be had in this world.” He goes on to conclude: “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

That’s what I told my 13-year-old daughter: her longing for an idyllic and unchanging home was really a longing for heaven. It was evidence that a part of her human soul still remembered Eden, and longed to go back. (“I was never in Eden!” she unpoetically pointed out, which is how my motherly talks often go over.)

Thanksgiving and Easter Point to Eternity

The good news—as we Christians say, the gospel—is that this universal human longing can be fulfilled. Christianity acknowledges what our hearts know to be true: death is wrong. We were meant to live forever. Far from being a benevolent part of the circle of life, death is an intruder and an enemy. But it’s an enemy whose days are numbered. “I am the resurrection and the life,” Jesus famously promised a dear friend, who was grieving the loss of her brother. “He who believes in me will live, even though he dies.”

Christians believe that just as Adam’s sin brought the curse of sin and death upon humanity, so Christ’s atoning death and resurrection breaks that curse for all who believe. Because he rose from the grave that first Easter Sunday, we too will rise from the grave and live forever. Death doesn’t get the last word. “The gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

It’s noteworthy, then, that the best comfort for my children over their small loss—and for all who feel the ache of living as immortal souls in mortal bodies—is ultimately found in the two holidays we always celebrate at Papa and Nanny’s house. On Thanksgiving, we remember that each day is a gift to treasure while it lasts, without any expectation for the future. On Easter, we celebrate the only reason mortal man can look toward the future with hope.

This world, with all its beauty and pain, is passing away. But Jesus’ death and resurrection has guaranteed us the eternal, perfect home for which our hearts long—a place where every tear is wiped away, and no one ever says goodbye.