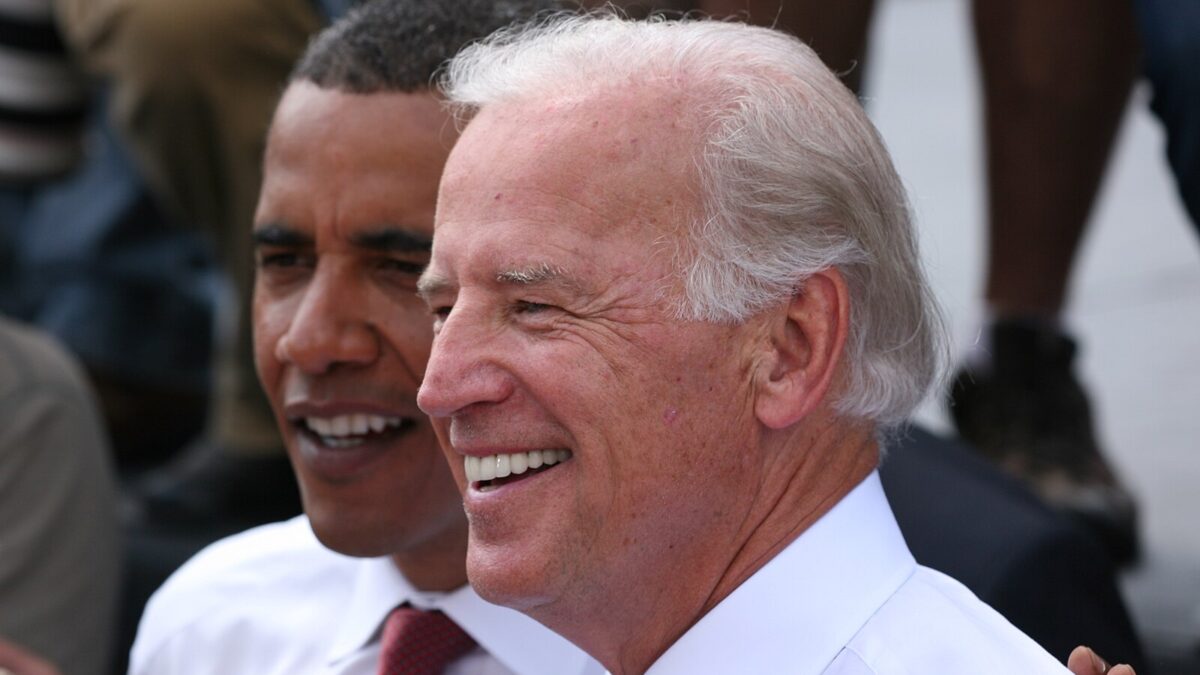

For all the attention to Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s resignation under apparent pressure from President Barack Obama and White House officials, the real questions may be why Mr. Obama appointed him in the first place and what the administration’s handling of Hagel—from start to finish—says about its priorities and the way forward.

Why did President Obama select and then dispose of Hagel? White House spokesman Josh Earnest has essentially said that Hagel was hired to supervise budget cuts and Pentagon reorganization and suggested that the Department of Defense needs different leadership for a war against the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). This is revealing in three important respects.

First, notwithstanding Hagel’s prior management experience in the private sector, the USO and the Veteran’s Administration, it is clear that what the administration really wanted was a Republican who would preside over declining defense spending to provide political cover. Who better for the task than a decorated combat veteran like Hagel who was also a former Senator and government and business executive? As quickly became apparent, however, the White House showed stunningly bad political judgment in expecting Hagel—right as he may have been to be skeptical of the war in Iraq and a potential war with Iran—to win easy confirmation. Democrats thought Hagel was a Republican, but (rather unfairly) many Republicans did not.

Second, while it is probably true that new leadership is necessary in the fight against ISIL, the problem seems to be less with the Pentagon’s civilian head but with the commander-in-chief and his close advisors. Few appear to remember that Mr. Obama himself earlier admitted precisely what Hagel was later reportedly complaining about in a memo to National Security Advisor Susan Rice: that the administration did not have a strategy to deal with ISIL. While the administration did develop plans in the intervening period, Hagel was frustrated by enduring and inherent inconsistencies in the White House plan to fight ISIL and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad at the same time. Thus the same president who said “I came to admire his courage and his judgment, his willingness to speak his mind” in appointing Hagel seemed rather less welcoming of Hagel’s real-world dissent.

Third, the White House has been utterly graceless in its treatment of a man who willingly subjected himself to the nastiest side of American politics in no small part to help President Obama and his administration politically. Hagel obviously wanted the job—so the fact that he was prepared to endure the confirmation process was not strictly an act of noble self-sacrifice—but as a prominent former Senator he could likely have found several more pleasant ways to spend the last two years. Instead, he endured mean-spirited personal attacks, often from interventionists in his own party who disagreed with his more calibrated approach to foreign policy or questioned his support for Israel, in order to win Senate confirmation. (Of course, Hagel’s purported comments about Israel now look quite friendly in comparison those of White House advisors using profanity to refer to Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu. Some outside observers even view him as Israel’s closest partner in the administration). Despite all this, anonymous senior officials are attacking Hagel’s performance and his reputation rather than allowing the president’s positive comments in his formal remarks to stand on their own. Chuck Hagel deserved much better from the president and the administration he served. This diminishes Mr. Obama.

Finding a Replacement Could Prove Challenging

It is unsurprising that administration officials have focused attention on former Deputy Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter and former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Michele Flournoy as potential successors to Hagel. While both look like competent and respected public servants, and each has already served in the administration, neither has the kind of high profile that would allow a significant challenge to White House (in the person of National Security Advisor Susan Rice) micromanagement of the Pentagon on ISIL and other issues.

More startling is that President Obama and Ms. Rice would readily embrace Senate confirmation hearings for a new Pentagon nominee in the current political environment. It’s not simply the fact that Republicans now control the Senate, that Mr. Obama is well on the way to alienating many Republicans over his executive order on immigration, or even that Senator John McCain—one of the administration’s harshest foreign policy and national security critics—is expected to become Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee and therefore to lead the hearings with Hagel’s successor. The big problem for the White House and for its eventual nominee is that the Obama administration’s foreign policy offers far too many opportunities for legitimate and very tough questions. Offering up Mr. Hagel as a sacrifice will not help the administration to dodge this.

More startling is that President Obama and Ms. Rice would readily embrace Senate confirmation hearings for a new Pentagon nominee in the current political environment.Hagel’s query—how to reconcile the administration’s war against ISIL inside Syria with its stated aim of ousting Assad, who currently seems to be one of the principal beneficiaries of U.S. policy—will be only the beginning of the pointed challenges to the president during the confirmation process. (One option would be to focus on the one that threatens U.S. security interests, ISIL, and to put more effort into a political solution in Syria since it should be clear by now that without a level of U.S. involvement that few want, only ISIL can defeat Assad.) The administration’s broader policy toward ISIL remains unclear too.

Beyond this, Mr. Obama’s approach to Russia and Ukraine has been ineffective and lacks well-defined practical goals; what does the administration think that economic sanctions will actually accomplish—and when? In dealing with China, the president has under-resourced a pivot to Asia that in retrospect looks less like a policy and more like an unsuccessful excuse to disengage from the Middle East. Moreover, while continued talks with Iran are probably better than the alternatives, the administration has not clearly articulated how it will prevent Iran from dragging out the process to its strategic advantage, not only by providing Tehran with more time to advance its nuclear program, but also by allowing Iran’s leaders to continue to dangle the prospect of cooperation against ISIL. When is the end of the road and what will happen when we get there?

In the end, for an administration that seems to base so many foreign policy decisions on its political convenience, finding a replacement for Chuck Hagel may prove quite inconvenient indeed.