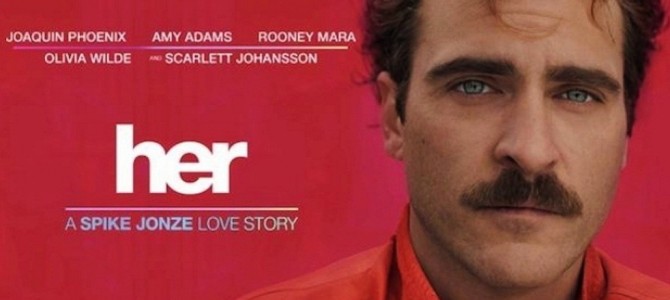

Late in the holiday season, I had the chance to view Her, the new film written and directed by Spike Jonze (whose previous directorial credits include Being John Malkovich and Adaptation). The movie stars Joaquin Phoenix as a down-on-his-luck writer in the Los Angeles of a not-too-distant future. He’s in the midst of a divorce he’s yet to make peace with and has moved from working as a journalist to creating “hand-written” letters (actually just computer-generated facsimiles of written correspondence) for hire.

In the film’s intentionally jarring opening scenes, we get a sense for the jaundiced view the script has of technology’s effect on relationships. Phoenix’s character, Theodore, doesn’t just occasionally string words together for an inarticulate suitor; In some instances, he’s penned both sides of years-long correspondences. This is a world in which it’s possible to outsource the entirety of human intimacy. The fact that Theodore works in an office swarming with other writers engaged in precisely the same craft subtly informs us that this is something more than a niche market.

This bit of background is important for those of you who haven’t seen the film, because it’s easy to infer from the marketing (and even from some reviewers, who should know better) that Phoenix’s character is a socially maladroit loner. If you know anything about the movie, it’s probably the one-sentence takeaway that it’s the story of a man who falls in love with his digital assistant (think of it as a hyper-advanced Siri voiced by an effervescent Scarlett Johansson). If Theodore’s a shut-in, that’s equal parts creepy and simplistic.

That’s not the character, however. Theodore is an affable co-worker. He’s a thoughtful friend. We see him be not only functional, but actually somewhat charming on a date. And the prose he constructs on the job shows us that he has a lyrical grasp of the beauty of human connection. He’s simply a man made gun-shy by the sting of love lost. He is singed perhaps; but not burned.

Theodore’s digital paramour, Samantha, is the product of the world’s first artificial intelligence-based operating system (and it’s a testimony to the film’s craftsmanship that you buy it). She’s charming, witty, solicitous about his feelings—apart from that little wrinkle about the lack of a corporeal presence, she’s the ideal girlfriend. And the film wisely chooses not to make Theodore some kind of freakish aberration. We learn later on that romantic relationships and intense friendships with this quasi-human OS are a widespread phenomenon. Indeed, it’s difficult to imagine that realistic entities created for the purpose of molding to the contours of your personality wouldn’t inspire that kind of devotion.

Upon learning that Theodore’s new love interest resides in his smartphone, his soon-to-be-ex-wife (played by Rooney Mara) utters one of the film’s key lines: “You always wanted to have a wife without actually dealing with anything real.” That seems to be the nub of what the films wants us to ponder: is technology expanding our capacity for meaningful relationships or undermining it?

I’ll put the perfunctory spoiler warning here, but it shouldn’t come as a surprise that a film that takes the subject matter seriously doesn’t deliver a happy ending for Theodore and the virtual object of his affection. No technology, after all, could meaningfully simulate the depths of human interaction without also replicating its liabilities—and that’s precisely what happens in Her.

We talk a lot here at Ricochet about relationships—specifically about the factors influencing the seemingly decreased societal reverence for marriage. We’ve heard a lot of culprits identified: the welfare state’s marginalization of the nuclear family; the unrealistic standards that the “you can have it all” mindset imparts to women; the notion that men no longer have the proper incentives to get married. Yet, while watching Her, it occurred to me that there’s something else we may be missing.

My generation especially (“millennials,” if you prefer a term that makes the group sound as if its existence will end in a cyanide-induced suicide) is utterly conditioned to personalization. Every young person’s iPhone menu is a personality index—an atlas of the self. With every one of our digital interactions calibrated to produce maximum satisfaction, we define adversity down. Who hasn’t reacted to an unwanted pop-up ad as if someone just drove a sedan into the living room? Who hasn’t attempted to fast-forward through commercials only to realize they’re watching live television and had their teeth set slightly on edge? The more our demands are met, the pettier our grievances become.

While this trend has been an economic and technological boon, it’s also lowered our threshold for pain. And pain is the tax that’s applied to love, no matter how deep or how true.

It’s not far-fetched to imagine, as Her does, someone so conditioned to perpetually having the world arranged to flatter his every idiosyncracy that he is willing to entertain the notion of a romance that is fake but effortless over one that is sincere but strenuous. That’s where Her terrifies you: when you realize “my God, people would do this.”

I see this trend in my contemporaries all the time. They’ll disqualify potential mates on the basis of Seinfeldian marginalia. If someone doesn’t tick every box—if they’re not the Match.com wish list made flesh—they may as well be the Elephant Man.

For this segment of the population anyway, we may be over-thinking the hangups with marriage. It’s not necessarily an outgrowth of economics, public policy, sociology, or religious belief. It might just be that love is hard. And, increasingly, ‘hard’ is something we’re not willing to do.

Troy Senik is Senior Editor at Ricochet, where this article originally appeared. He is currently a columnist and member of the editorial board at the Orange County Register, a Senior Fellow at the Center for Individual Freedom and the host of a series of podcasts for the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.