I can’t remember what was on the menu in the cafeteria that day, but chances are it was either grilled cheese sandwiches or tuna casserole. Back then my public elementary school in Southern California adhered to meatless Fridays.

On November 22, 1963, I was sliding my tray down the laminated lunch table to my appointed spot when Jennifer zeroed in on me out of nowhere – an unusual breach of discipline – and announced: “Stella! Did you hear? President Kennedy was shot today!”

I stood there speechless, watching Jennifer watching me. As the shock deepened on my face, she seemed to take it in with a smile of discovery, like an infant beginning to act out stimulus-response.

“He was killed!” My jaw had already dropped. And she watched me a bit more before adding a detail – in sing-song — to prove it was for real: “In Dallas, Texas.”

She then zipped away, likely in search of another unsuspecting fourth grader before the news became so quickly widespread she was no longer the bearer of it.

I think because of the shock, my senses became sharpened to so much about the day. The jolt of it was not really about John “Jack” Kennedy, the icon. The killing of the president of the United States was quite enough of an earthquake on its own. I grew up among staunch Democrats who detested Richard Nixon, but it would take maybe another week or so for me to sign on to the cult of the man and his martyrdom, after it was kneaded by the media into the culture. But not just yet.

The day itself lives in my memory mainly because it provided another lens through which I could see the people in my world. I saw the flag at half-mast in the blue sky at recess after lunch. It had just been lowered by the school’s custodian, Mr. Landis, a quiet and thoughtful man. I had never seen the flag fly that way before and asked the playground supervisor about it. She softly explained for me, while most of the kids were noisily running around at play, despite the news.

I had a short chat with a classmate, Cindy, alone in the girls’ lavatory. We spoke about how we would always remember where we were that day. But what struck me most about the conversation was that Cindy, a popular girl, didn’t talk to me under normal circumstances. I pondered the fact that bad news made me seem more normal or human to some people.

Then there was the somberness of all the grown-ups. Back in the classroom after recess, my teacher Mrs. Striker wept right in front of us. She sat there with a pocket-size transistor radio, held to her ear and repeated it for us since it was too faint and static-infused for a whole classroom to hear. I learned that the new president would be a man named Johnson. I heard that another guy – his name was Connally – was also shot. We didn’t do much else the rest of the day. As always, I took bus number 9 home, and I remember the familiar smell of it. Two days later I’d hear my mother’s cries of shock in front of the TV as she watched live footage of Jack Ruby killing the suspected assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald.

Big events serve largely as a compass for one’s life, defining markers of who we were, where we’ve been since, and our relationships to others. And maybe that’s an underlying value of these recollections for so many of us, even though we prefer to talk about the externals. When we recall the event, we are able to recall what we were doing, how we were feeling, and maybe gauge how much we’ve changed in the interim. We recollect a different era, older technologies, a seemingly different social order, a discarded outlook.

It seems that people are longing for a certain glory when they mourn Kennedy. We may have all felt the lure, the human urge to idolize certain charismatic people as nearly divine. In the 50 years since, however, we seem to be seeing a bit less of that and more JFK biographies of the “unauthorized” variety that glare less forgiving light on his flaws.

The Day C.S. Lewis Died

In the meantime, a few more people have become aware that November 22, 1963, also marks the day C.S. Lewis died. Like JFK, Lewis was also known affectionately to his friends and family as “Jack.” But the similarity seems to end there.

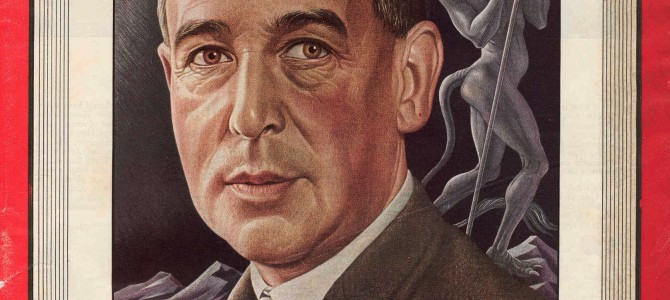

Though Lewis was an intellectual giant of the 20th century and popular Christian apologist whom Time Magazine featured on a cover in 1947, his death was obscured by JFK’s assassination. But his legacy continues to bear fruit. Lewis had a knack for bringing the faith richly to life, clarifying it for any reader or listener to his BBC talks. And as a former atheist, Lewis knew the playbook of the opposition well, which was infuriating to his detractors. Many such detractors are still very busy today.

But I hadn’t even heard of C.S. Lewis until I was in my 20s. Now it astonishes me that his lifetime actually overlapped mine and that I can remember what I was doing on the day he died. His influence has put down very deep roots in me, and so many others, including two generations who have been born since his death. In fact, his children’s books are more popular than ever and have recently been made into major films for the box office.

The coincidence of JFK and C.S. Lewis dying on the same day gives us a lot to ponder. Many people mourned and adored Kennedy for his worldly glory, his seemingly superhuman qualities – brilliance, style, good looks, and being “Mr. Camelot” himself. By contrast, Lewis, the stodgy looking medievalist at Oxford, would have been the actual specialist on the legends of Camelot, and the enchantment it holds for us. But Lewis also might have reminded all who mourn that they are really yearning for something else: an eternal glory. It’s a glory that we can sense through beauty, but it’s elusive, and yet it lives in us. In his essay “The Weight of Glory,” he explains: “We want something else which can hardly be put into words – to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into it, to receive it into ourselves, to bathe in it, to become a part of it.” Yet worldliness stifles us from recognizing this.

“There are no ordinary human beings,” Lewis insisted. And he meant it literally: “ … it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit – immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.”

JFK famously instructed us to “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.” But Lewis was on another plane, showing us the potential of what we might do for each other by recognizing and honoring the glory that lay in each and every human being.

Lewis’s legacy will continue to shape history in ways deeper than JFK’s. (Or, for that matter, more than Aldous Huxley, author of “Brave New World” who, interestingly, also happened to die on that same Friday.) The fact is that so many of Lewis’s insights on human folly and the nature of evil are in brisk circulation, very readable, compelling, and potentially life transforming to whomever may stumble upon them.

And today people are more frequently consulting Lewis’s 1943 lecture “The Abolition of Man” because it’s so breathtaking in its prescience. In it Lewis warns about the debunking of objective reality in education, which amounts to the mocking of virtue and honor. This opens the door to abuses in technologies that doom our humanity. So we end up clamoring “for those very qualities we are rendering impossible.” He illustrates the irony and madness of it all with this splendid line: “We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

Later, Lewis’s children’s books, “The Chronicles of Narnia,” would shed much light on the mysteries of human interactions. “The Screwtape Letters” would serve as Exhibit A on the exploitative nature of evil whenever it gets to cash in on human folly. He also wrote science fiction, poetry, and thoughtful letters back to everyone who took the time to write to him.

Lewis was what many social workers today would call a “caregiver.” His personal life was sacrificial in many ways, as he reached out to alleviate the suffering of others. When a friend was killed in World War I, Lewis took care of the friend’s widowed mother – and lived with her for life. His brother who had alcohol issues also lived with them. And when Lewis was 57, he married a woman who was dying of cancer. She also happened to be divorced, a mother of two boys. Before they were married, Lewis dedicated his masterpiece to her, the novel “Till We Have Faces.”

Both Kennedy and Lewis had very public lives. Kennedy’s of course was a whole lot more so. But C. S. Lewis broadcast well and universally so much insight about what it means to be human. And because of that, the roots of Lewis’s legacy run not only very deep, but very wide.

Lewis also had a profound understanding of women – more than any male author I’ve read. Consider his complex and textured portrayals in “Till We Have Faces” of the extraordinary sisters Orual and Psyche. Orual faces much cruelty as a child but grows into a brilliant ruler who can be very cruel herself. The adored and kind Psyche, chooses a self-sacrificing path of joy that Queen Orual neither understands nor accepts. It captures a picture of what many women go through and feel. But this is likely because Lewis had such a profound understanding of humanity in its wholeness. And also because he was such an astute observer of behavior, particularly patterns of behavior among his own sex. Here he even explains the phenomenon of “the man cold”:

“I have a notion that, apart from actual pain, men and women are quite diversely afflicted by illness. To a woman one of the great evils about it is that she can’t do things. To a man (or anyway a man like me) the great consolation is the reflection ‘Well, anyway, no one can now demand that I should do anything.’”

Much of C. S. Lewis’s writing continues to reach out in love to anybody trying to make sense of the pain and chaos of human relationships and the world we live in. We’d do well to remember his legacy on the 50th anniversary of his death this November 22.

Stella Morabito writes on society, culture, and education.