Earlier this month in a north Dallas suburb, students at Little Elm High School staged a walk-out in protest of a sexual assault allegation they say school administrators failed to address. What started as a peaceful assembly soon escalated into a violent conflict that led to four arrests and the use of pepper spray and tasers on teenagers.

Unlike a similar protest that happened at nearby Guyer High School a month earlier, the protesters at Little Elm High School were mainly students, not adults. Also, instead of marching around the school peacefully, the protesters attempted to enter the school and presumably confront its principal, Dr. Gerald Muhammad, in his office. According to witnesses and videos, students were shouting and banging on windows and doors.

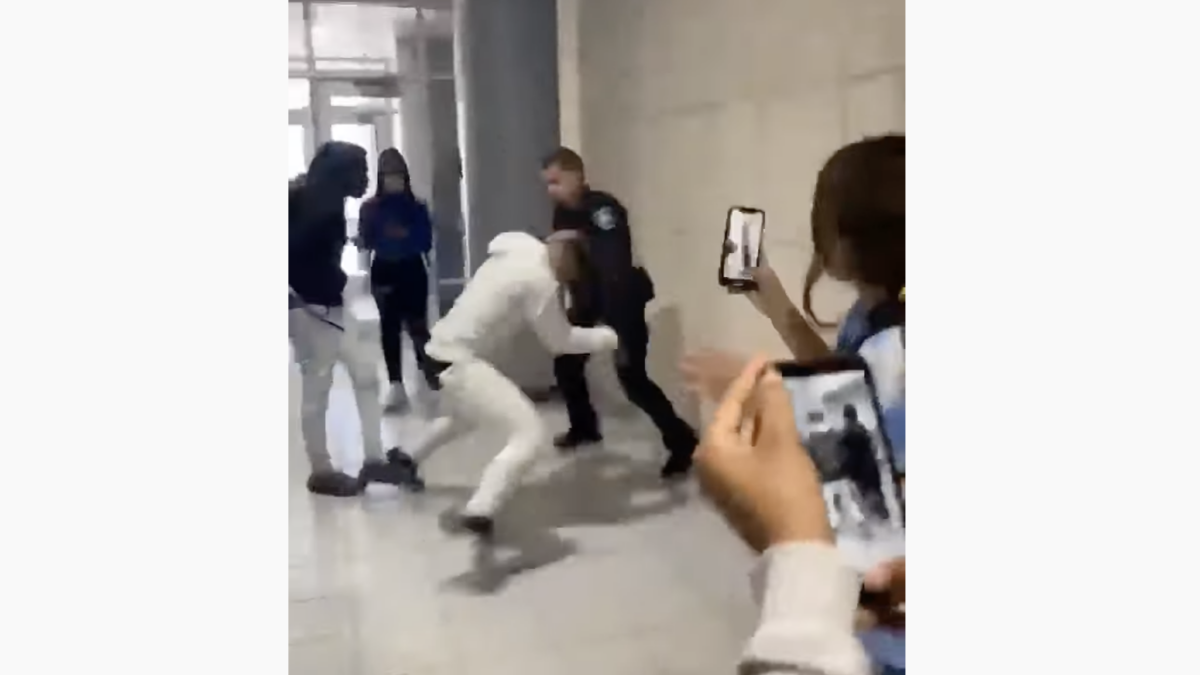

This led administrators to summon the police to “calm” down the situation, which soon became a “major disruption,” according to local news reports. Far from diffusing the tension, police took aggressive action against some of the students, wrestling a young woman to the ground, tasing a young man, and using pepper spray on another student.

By the end of the whole affair, four students were arrested and the district issued a statement taking no responsibility for what transpired. They blamed a social media post for spreading misinformation about the situation and justified their decision to call in law enforcement. Some parents complained of the excessive force and the permissive attitude towards alleged sexual abuse, but there has been no indication that either the school or local authorities will take any further action regarding the alleged victim or her advocates.

While it would be easy to write off the whole thing as a group of juvenile delinquents using an online rumor as a pretext to rampage through their high school, this would ignore some troubling issues that have become systemic in schools, particularly this year.

First, it must be understood that many school campuses, even those in the suburbs, are not safe places anymore. Fights between students, bullying, and even gun violence are becoming more common, and students are understandably more anxious and depressed. The National Association of School Resource Officers reports that gun-related incidents tripled this year compared to 2019.

This protest is already the third public instance of campus safety being compromised in a Texan high school within the past month. The first was the shooting at Timberview High School in Mansfield ISD. The second concerned an alleged serial sexual abuser at Guyer High School in Denton ISD. The third was the sexual assault allegation and subsequent outcry in Little Elm ISD.

Whatever side one takes in these matters, it’s clear that all students, particularly female students, are running increasing risks of being bullied, harassed, or assaulted when they go to school. This has been made worse by school shutdowns that have delayed maturity and introduced antisocial habits in many students at the most formative time of their lives.

A recent online petition addressing the Little Elm uproar alleges a freshmen boy targeted a sophomore girl and violated her personal space, first through harassment and then through unwanted touching and groping on a school bus. Whether the allegations prove to be true or not, the adults in charge should have intervened in this situation, investigated the matter, and disciplined any found responsible accordingly.

But they didn’t. When the girl reported the abuse to an administrator and school resource officer, she simply wasn’t believed, a local outlet reports. Instead, they took the side of the boy who was accused and assigned the girl three days of in-school suspension because she made a false accusation and apparently confronted the boy when she was told not to.

Based on my years of experience teaching in public schools, this happens all the time. School administrators can always claim there’s “insufficient evidence” to punish an accused student. If they seriously investigated the issue, it would require police work such as looking at camera footage, taking statements from other students, and reviewing student disciplinary records. What’s more, if they find the accused student guilty, there would be even more paperwork to determine and carry out the proper punishment.

Furthermore, if school administrators are willing to punish this student, then they need to start doing the same for the other guilty students, resulting in more work, more suspensions, and potential charges of racism if the guilty students happen to be black.

In a political environment that stresses equity and minimizing consequences for criminal behavior, there is far more incentive to ignore and discourage reports of bullying and sexual assault than suspending or expelling any bad students. This pressure is why so many school districts have adopted various forms of “restorative discipline” in which they stress therapy and dialogue over investigation and punishment. Restorative discipline does cut down the number of referrals and suspensions, but it also results in much more chaotic campuses.

All this leaves victimized students and their parents with few options. Either they can enlist the help of fellow students to fight on their behalf or they can organize a protest and try to gain public attention. What happened at Little Elm High School seemed to be a mix of both: in one sense, it was a protest against the administrators’ inaction; in another sense, it was a mob intending to intimidate authority.

This makes it difficult to fairly judge the whole thing. The students had every right to assemble and demand justice, but provoking police officers detracts from their cause. Any demand for accountability is undermined by anarchic behavior. Instead of banging on windows and threatening administrators, the students should have involved more adults and spokespeople to articulate and publicize their grievances and call for action.

That said, the protest has succeeded in reopening the investigation of the case that prompted the protest and has resulted in the creation of an independent committee to review sexual assault cases. This is only one step in the right direction. There is still more to do to prevent these cases in the first place. After all, the goal should be to make schools safer, not improve the district’s optics in order to fend off any more protests.

In much the same way that cities have become crime-ridden danger zones due to the literal and rhetorical diminishment of law enforcement, schools are now falling into the same patterns for the same reason. Teachers and administrators are portrayed as perpetrators of injustice if they take serious action against the bullies and predators on their campuses, so they have stepped back.

Until this dangerous cultural dynamic is resolved, or until the government empowers parents to choose where they send their children to school, we can expect more protests and outbreaks of violence, as well as a precipitous decline in the quality of instruction. Hopefully, political and educational leaders can take heed from the lessons of Little Elm High School and restore order, if not for the sake of justice, then at least for the sake of the children.