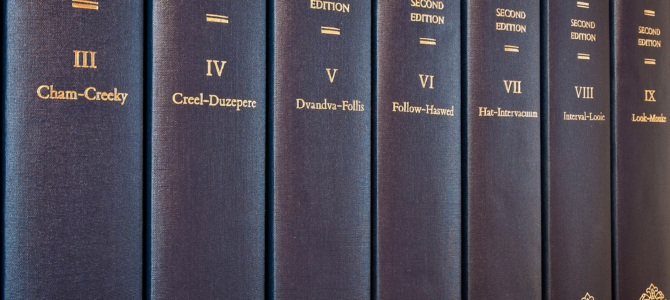

The next time you hear someone describe antisemitism as a problem of the uneducated, suggest they flip through the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The august dictionary recently published a slew of new words for inclusion, many with a Jewish connection. That would all be ho-hum, if it weren’t for the way some of these words are presented, underscoring that even something as mundane as a dictionary can help elevate and circulate bigoted language.

What’s clear, if you read OED’s explanation for how words are added to its lofty ranks, is that these decisions are not made in haste. “Editors consider thousands of word suggestions from these sources every year. … [S]uggestions for words with sufficiently sustained and widespread use are assigned to an editor.” Research is conducted involving “several specialist teams.” It’s a whole process.

Yet, amazingly, in spite of significant attention, it appears no one at OED looked askance at how it displayed some incredibly charged words. I say “appears” because OED did not respond to my query in time for publication.

New OED Definitions Are Problematic

The problems with OED’s new words fall into three main categories. First, I have trouble believing some of these words are widely used and deserve a spot in the dictionary that calls itself “the definitive record of the English language.”

Take “anti-Semiticism,” which is an unnecessarily clunky way to say antisemitism. There’s also “kibitz,” which OED primarily defines as an American way to describe the spectator of a game. The only usage this American is familiar with resembles OED’s second definition and should be spelled “kibbitz.” I’d define it as aimlessly conversing in a jovial and joking manner.

Second are entries that require clarification. “Yekke,” a term for German Jews, can be used anywhere there’s a Jewish community, so it’s unclear why OED cites “Israeli Jewish usage.” This Jewish mother, of course, also couldn’t help but notice that “Jewish mother” is considered a “sometimes derogatory and offensive” epithet, described as “overprotective, overbearing, or interfering.” I know myriad Jewish mothers who defy that defaming definition, but negative stereotypes never care about real-world particulars.

“Jewish joke” is poorly explained as “a joke told by or considered characteristic of Jewish people,” without detailing that Jewish humor skews dark and is the ultimate coping mechanism. And defining “Jewish question” as “a question or debate about the appropriate status, rights, and treatment of Jewish people within a nation state or in society in general (often in anti-Semitic contexts),” remarkably underplays that this “debate” about Jews helped fuel the Holocaust.

Finally are terms best categorized as slurs. The OED includes ugly language for other religious, racial, and ethnic groups — I checked — but why doesn’t it consistently highlight that none of these words should ever be used in polite conversation?

OED’s Editors Don’t Understand What’s Offensive

OED’s editors clearly label “Papist” as “chiefly derogatory” and tell us “Wop” is “now considered offensive” — as if that hadn’t been true for at least a century. But you have to read deep into the N-word’s definition to learn it “only began to acquire a derogatory connotation from the mid 18th [century] onwards.” Oddly, the editors didn’t flag this as one of the 21st century’s most incendiary words.

Among the new Jewish terms, “Jew town” and “Jew York” are Exhibits A and B. They are not positive or even neutral terms, as OED staff might observe from the “Hymietown” scandal of 1984. “Jew town” is described as “colloquial (now potentially offensive even when used without derogatory intent).” Forget potentially, OED; the term is offensive.

I’d also like to know when anyone would say “Jew-free,” which OED defines as “characterized by the absence of Jewish people” and references the German Judenfrei, without wanting to convey hostility toward Jews. Dictionary users should be advised this phrase is laden with huge historical baggage.

“Jew-like,” which OED calls “often derogatory and offensive” — as opposed to always derogatory, apparently — should also raise eyebrows. OED explains it as “in a manner (stereotypically) regarded as characteristic of a Jewish person.” Whoever uses this term must not understand that Jews, like people everywhere, vary widely. Of course, these may be the same people who regularly make “Jew jokes,” defined as jokes “making fun of Jewish people” and that likely miss all the real humor inherent in Jewish jokes.

OED Editors Must Be More Responsible

There’s something to be said for a dictionary encompassing a wide array of words, so all English speakers can fully understand what’s being written and said across the English-speaking world. Given resurgent antisemitism and the loaded nature of many of the aforementioned terms, however, responsible editors bear an extra burden to clarify which words would be welcome in conversation with or about Jews versus which ones are likely to cause offense.

If the OED wants to include fraught words for the sake of the linguistic record, it should be consistently explicit about any charged associations. Otherwise, with all its labor and resources, the OED will have failed not only in its mission to clearly define all of the English language but also as a force for upholding civilization.