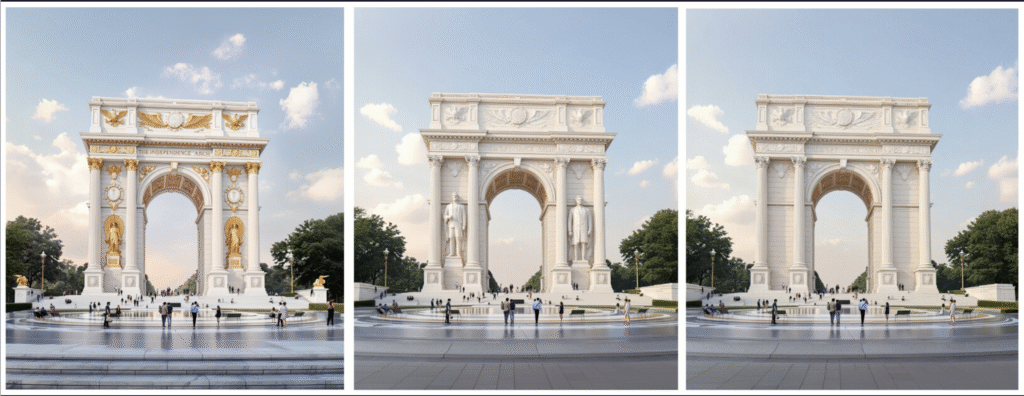

President Trump posted to Truth Social a few weeks ago three renderings for the proposed triumphal arch soon to be erected in Virginia’s Memorial Circle, which will frame the Lincoln Memorial and Arlington National Cemetery together in a tasteful ensemble for America’s 250th Birthday.

Right on cue, the artistic establishment, long a citadel of aesthetic terrorism that possesses a near religious zealotry for modernism, expressed its derision. This is merely predictable given that critics have long panned President Trump’s penchant for Classical Architecture, exemplified in his Mar-a-Lago residence built by the heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post (who also dwelled in Washington’s celebrated Hillwood Estate) as “Temu Baroque,” a cheapened simulacrum of what had once been.

Citadel of Modernism vs. The Classical Revival

While classical architecture at its finest rests on bespoke artisan craftsmanship, something not apparent in the president’s Oval Office renovation, which relies more on pastiche, that is ultimately beside the point. President Trump should be praised for finally addressing an issue long ignored by political and artistic elites: the public’s persistent opposition to ugly, federally funded architecture that fails to live up to the dignity and grandeur of the Republic.

Sadly, leftists who see all art as inherently laden with political implications, such as Rep. Katherine Clark of Massachusetts, the third-highest-ranking Democrat in the House of Representatives, do not see it this way, replying to the president’s renderings with the tired non sequitur that “Americans cannot afford health care.”

This controversy echoes earlier uproar over his 2020 executive order, “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again,” which sought to make neoclassical design the default for federal architecture but was criticized in a New York Times editorial asking, “What’s so great about fake Roman temples?” and warning that mandating a single aesthetic style smacks of “authoritarian overreach rather than democratic pluralism.”

The Arch as Civilizational Language

Motifs of Classical Architecture, such as triumphal arches, however, are not merely artifacts of a bygone empire. It is a declaration of belief, much like our nation’s founding document, that history has meaning, that victory is not achieved by mere accident but through prudence and grit, and that order is not only desirable but a necessary precondition for virtue. When art critics, many of whom C.S. Lewis would probably have called “men without chests,” dismiss proposals to revive such forms as authoritarian nostalgia rooted in kitsch, they commit a fundamental error: the arch has always represented a civilizational language through which the West, confident in its convictions, enacts a triad of truth, beauty, and human flourishing.

This is evident in the apotheosis of modern triumphal arches: the Arch of Constantine, which fused the West’s three great inheritances. From the Greeks came the pursuit of the eternal true, good, and beautiful; from the ancient Jews, the quest for the one, true God and the moral life necessitated from the desire to live in communion with him; and from Rome itself, a desire for nobility and grandeur that elevated public life through form, hierarchy, and law.

Constructed in honor of a Roman emperor whose conversion to Christianity would later earn him the title “Co-Equal to the Apostles” in the Eastern Church, the Arch of Constantine stands at the intersection of these traditions, translating metaphysics into stone. Recycling pagan reliefs while inaugurating a Christian empire, the arch, borrowing a phrase from post-Vatican II conciliar rhetoric, embodies a hermeneutics of continuity, rather than the rupture advocated by adherents of Gibbonian historiography.

That synthesis, however, is not limited to the ecclesiastical. Secularism à la laïcité presents a false binary between Church and State, one that would have left most Western statesmen before 1900 completely confounded. The Arch of Constantine, in particular, served not merely as a historical artifact but as a generative model, instructing Western architects long after Rome’s political fall.

Luminary examples include Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Washington D.C.’s Union Station, and Brussels’ Cinquantenaire Arcade. Each speaks in a distinct historical key, yet all remain mutually intelligible, singing from the same architectural chorus and perpetuating the West’s enduring affirmation that history is intelligible, public life is worthy of elevation, and political order remains inseparable from moral meaning.

Moreover, this continuity reveals something essential: true innovation does not arise from mere abstraction, but from appreciation for inherited form. Constantine’s Arch itself was an act of creative recomposition, demonstrating that originality does not have to entail adoption of a Year Zero mentality. In the Burkean sense, Civilizations innovate not by bulldozing the past, but by re-working it, allowing old forms to be rejuvenated in order to speak to new circumstances. Contemporary artists such as the painter Giorgio Dante, who seeks to revive the style of the Renaissance Old Masters and the sculptor Gaylord Ho, whose work much like Art Deco appears concurrently classical yet strikingly modern in particular, do a wonderful job of making the old seem new again, which, even if not explicitly acknowledged, is profoundly Christian in spirit.

The political philosopher Patrick Deneen captured this sensibility succinctly, observing that the reactionary looks only to the past, the liberal confines himself to the present, and the progressive fixates on the future, while the conservative seeks to bind all three together. That a vision for the future comes from the end-result of productive dialogue between past and present. It remembers what came before, speaks to the present civic order and gestures towards permanence beyond the moment. Thus contrary to art critics who think a duct-taped banana at Art Basel Miami is hunky dory, the triumphal Arch is not nostalgic, but is rather integrative in relation to time and space.

The Body as Metaphysics

At the heart of this integration lies a particular anthropology. Classical and neoclassical architecture are grounded in the human body itself. Proportion, symmetry, and hierarchy derive from embodied reality. Columns echo limbs, façades mirror torsos, and sculptural figures such as atlantes and caryatids quite literally bear weight. These figures are not ornamental flourishes. They dramatize a moral claim: dignity is not found in weightlessness or self-creation, but in strength ordered toward form, burden accepted rather than denied.

This claim is deeply unfashionable in our time. Contemporary art increasingly treats the body not as a gift to be honored, but as raw material to be manipulated. The performance artist Orlan, whose surgical alterations are celebrated as acts of liberation, exemplifies this worldview. Flesh becomes a canvas, pain a medium, and identity something asserted against nature rather than discovered within it. What appears transgressive is, in fact, metaphysically impoverished, perfectly aligned with a technophilic culture that views the body as a platform to be optimized, mutilated in the name of living out “one’s truth” or outright discarded.

Camille Paglia diagnosed this tension decades ago. In Sexual Personae, she wrote that “nature is a brutal force, and culture is an artificial order imposed upon it.” The classical tradition understood this truth without illusion. Culture does not abolish nature; it disciplines it. Form arises not from denial, but from reverence. By contrast, much contemporary aesthetics collapses culture into nature, leaving only manipulation where meaning once stood.

It is here that the triumphal arch reemerges not as nostalgia, but as intervention. It insists that limits are not oppressive, that form is not arbitrary, and that the human body is not a problem to be solved. Where postmodern aesthetics revel in fragmentation and irony, classical architecture insists on harmony. Where our age treats embodiment as an inconvenience, the classical tradition treats it as a mystery.

This is why neoclassicism makes a radical claim today. Its greatness lies not merely in historical memory but in truth. It proposes that beauty is objective, that proportion reflects reality, and that the body, rightly understood, reveals rather than obscures meaning. In theological terms, it aligns with what Pope John Paul II articulated in his Theology of the Body: that the body “makes visible what is invisible.” Architecture, like the Incarnation itself, gives form to metaphysical claims.

The discomfort provoked by monumental classical projects reveals less about their alleged authoritarianism than about our unease with judgment. Beauty implies hierarchy. Proportion implies order. And order implies that not all visions of the human person are equal. In an age of moral relativism, this is an unsettling proposition.

Yet civilizations do not remember themselves through slogans or abstractions. They remember themselves through stone. The triumphal arch, whether ancient or modern, stands as a reminder that the West once believed and could believe, once again, that the human body is deserving of reverence, history has no expiration date, and beauty is worth defending. To recover that language is not to retreat into the past, but to affirm, against abstraction and amnesia, that truth can still be made visible.