Few institutions are more misunderstood in the 21st century than marriage. Even among devout Christians, it has come to have a multitude of different meanings. Setting aside the usual controversy of the last two decades of whether marriage must be between a man and a woman or simply any combination of people who claim to “love” one another, there are many other ongoing debates on the topic. Is marriage a contract or a sacrament? What are the rules on chastity? What role do children play in the marriage?

Typically, the answers to these questions would be answered by a community’s moral and spiritual authorities and regularly discussed among everyone since marriage is so crucial to a healthy society and happy individuals. However, under the guise of being more “pastoral,” these authorities have instead worsened the confusion, giving their blessings on every kind of definition for marriage — or they scarcely mention marriage at all. Even for an orthodox Catholic like myself who has attended Mass his whole life, much of what I thought about marriage came more from pop culture than the pulpit.

As an antidote to this problem, the Catholic professor and composer Peter Kwasniewski proceeds to systematically define, analyze, and evaluate marriage in his most recent book, Treasuring the Goods of Marriage in a Throwaway Society. As such, Kwasniewski takes a more theological and philosophical approach to the subject, respecting his reader enough to follow along. By the end of the book, he not only debunks the many modern heresies and myths concerning marriage, but he also reveals just how beautiful and holy marriage truly is.

Kwasniewski breaks up his argument into four sections: “Marriage and Family,” “Living Chastely,” “Virginity and Celibacy,” and “Contraception and Abortion.” His first section establishes the foundation and framework of his argument by defining marriage in all its fullness. Above all, he stresses the oneness of marriage, in which both a husband and wife belong to one another in all dimensions: “a nuptial vow is the binding together of two spirits, so that their grace, peace, joy, and charity may overflow into and be reinforced by their bodily togetherness.”

This understanding obviously clashes with modern notions of marriage which seek to affirm a person’s individual good above all. People can repeat the empty slogan, “love is love,” but without a religious context and absent of God’s grace, the marriage quickly becomes precarious and spiritually corrosive: “This is exactly the modern pattern: rampant fornication, promiscuity, multiple divorces, and the enormous heartache caused to spouses, children, and other relatives who must live among the rubble of collapsed marriages.”

Of course, this equally applies to the opposite reality for many adults who never find their soulmate, never marry, and suffer from chronic loneliness. Kwasniewski explains how so much of this is a consequence of a materialistic understanding of marriage. The spirit that gives the relationship life eventually dissipates, leaving emptiness and strife in its wake.

There’s little any believer would argue with in this first section. However, this changes in the following two sections, when Kwasniewski considers the responsibilities and proper limits of marriage. It is here that Kwasniewski handles the thornier questions of marriage like allowing divorced and remarried Catholics to receive Holy Communion, living chastely in marriage, dealing with a culture that’s hostile to traditional Christianity, rejecting all forms of contraception, and honoring priestly celibacy.

Because religious and moral leaders — not least, Pope Francis himself — have either softened on these matters or outright contradicted them, Kwasniewski is forced to take on the unpopular task of articulating what has always been the church’s position: Catholics living in sin cannot receive Holy Communion; they cannot act in lust or tempt others to do the same; they cannot endorse any aspect of the LGBT agenda; they cannot use contraception, inside or outside of marriage; and with very few exceptions, the priesthood must remain celibate.

Along with St. Thomas Aquinas and Aristotle, Kwasniewski cites a number of philosophers and theologians, both ancient and modern, as well as Holy Scripture to bolster his arguments. Besides demonstrating the reasoning behind the church’s seemingly anachronistic positions, this abundance of evidence helps to diffuse the strong feelings that people have about these issues.

Nothing about what he is writing is arbitrary; it is the result of intense reflection and debate throughout the centuries. When such conclusions about marriage are conveniently forgotten for the sake of keeping up with the times, the joy and beauty of marriage become impossible to realize: “We have forgotten what the day [a happy and holy marriage] looks like; we might wonder if the dawn will ever come; we could be deceived by the evil one into believing that night has won and the day has been vanquished.”

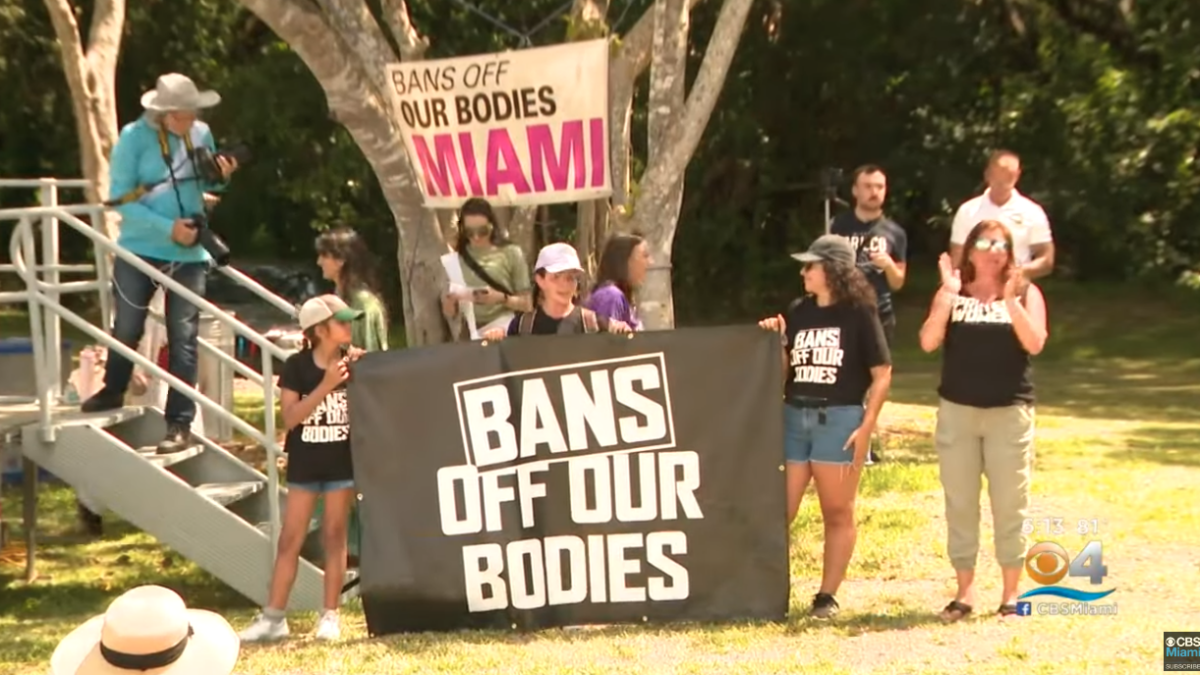

In the fourth and final section, Kwasniewski takes up the horror of abortion, a crisis that stems directly from today’s distortion and corruption of marriage. After all, once marriage serves the personal needs of individual adults and ceases to be about children, those children become an intolerable burden, thrown away like trash. On this front, Kwasniewski’s words cut through the equivocations and distortions of the pro-abortion left and get to the heart of the matter: “Materialism … is a system that can only be abused because it only leads downward, into the pit of utilitarian egoism. There is no possible room for human dignity and human rights.”

Overall, Kwasniewski is largely successful in his goal of recovering the traditional meaning of marriage and clearing away the misconceptions that cropped up in the past few decades. However, in his efforts to set the record straight, his book suffers from two flaws. First is his tendency to stray into some of the more obscure points of Catholic theology and, second, his lack of sensitivity to his opponents.

The first flaw is not a major problem, especially if the reader happens to be a traditionalist Catholic who has read some of the Summa Theologica, but for anyone outside this tiny group, some of Kwasniewski’s claims seem to appear out of nowhere. Such is the case when he touches on issues like St. John Paul II’s “Theology of the Body,” the sacramental superiority of the holy orders over marriage, the disastrous liturgical reforms of Vatican II, or the appropriate use of natural family planning. Although there are spirited debates on these issues in certain corners of the internet, they’re not exactly essential to Kwasniewski’s argument, nor are they inherently interesting.

The second flaw is also not major, nor is it really Kwasniewski’s fault. He is speaking “hard sayings” to an unserious culture, and his words are bound to rattle even the most sympathetic audience. Nevertheless, there are points in the book where he could be more charitable to his opponents and give them the benefit of the doubt.

For instance, even if people who divorce their abusive spouses or use contraception to space out pregnancies might be ultimately in the wrong according to Catholic teaching, it’s unfair to assume they’re just selfish or hateful. These teachings are serious stumbling blocks for many believers, and they deserve more compassion and patience from people like Kwasniewski who actually know enough to answer their objections.

Aside from these drawbacks, Treasuring the Goods of Marriage in a Throwaway Society is an important book that speaks to a critical problem threatening the stability, and indeed the very future, of the developed world. For so long, society’s leading intellectuals pointed out what’s wrong with marriage and sought to redefine it, which precipitated today’s crisis. Finally, there’s a book taking the major step of explaining what’s right with marriage, recovering its true definition, and restoring it to a place of honor.