All male criticism of Taylor Swift must be a manifestation of misogynist hyper-masculinity. At least that is the takeaway from Washington Post gender columnist Monica Hesse’s Sept. 28 op-ed regarding the recently reported romance of Swift and tight end Travis Kelce.

Hesse quotes random representatives of the “super-alpha-fragile-istic fringe of the football side,” in support of her claim, and for good measure ropes in a recent Federalist piece by Mark Hemingway on Swift’s music. Hesse, who for some reason refuses to cite Hemingway by name, grossly mischaracterizes his arguments by (falsely) claiming Hemingway’s complaint is only that Swift writes about breakups, heartbreak, and “how things made her feel,” and that his critique is little more than the stereotypical patriarchal double standard foisted upon women.

Not that Hesse’s finger-wagging at male criticism of female celebrities is all that unusual. Whether we are talking about the faltering U.S. women’s soccer team, obese female musicians, or self-obsessed actresses, there is an inevitable chorus speedily rising to defend them and accuse their detractors of sexism and misogyny. Yet this reality exposes a delicious irony of the women’s rights movement since its very beginning: the fragility of the feminist ego.

The Double Standard Often Goes the Other Way

Megan Rapinoe in August forced the exit of the U.S. women’s soccer team from the 2023 World Cup when she missed a penalty kick in the team’s round-of-sixteen match against Sweden. Afterward, midfielder Lindsey Horan declared she was “proud of every player that stepped up to take a penalty today” and that it was “courageous to go take a penalty” kick. First Lady Jill Biden in turn told the women’s team they had inspired “girls everywhere to show up and fight for their dreams.” As The American Conservative’s John Hirschauer noted: “That is the sort of thing you say to a child, not a professional athlete.”

Of course, women’s soccer is not all that unique among professional female sports. Simone Biles was named Time magazine’s 2021 Athlete of the Year, for not continuing to compete in the Tokyo Olympics. Naomi Osaka the same year was lauded for withdrawing from the French Open to address her anxiety and “prioritize her well-being.” Proponents of the WNBA meanwhile vacillate between celebrating higher audience interest in women’s basketball and complaining that the sports industry doesn’t give them enough coverage. (Truth is, 12 million people watched the 2022 NBA finals; the WNBA championship garnered less than half a million).

There are plenty of examples outside of sports. Until Lizzo was (ironically) accused of “weight-shaming” and sexual harassment, many were her defenders as a symbol of the fat-acceptance movement. When their work is questioned, “strong” female journalists such as Felicia Sonmez or Taylor Lorenz immediately play the harassment card — usually citing harmless, anonymous, obnoxious social media users — and claim they suffer from PTSD.

Feminists Want Women to Be Treated Like Men, Except When They Don’t

Since Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 book, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a constant rallying cry has been the demand for equal treatment. “We need to see men and women as equal partners,” 20th-century feminist writer Betty Friedan declared. “Women will only have true equality when men share with them the responsibility of bringing up the next generation,” argued Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

But do feminists actually want equality? Feminists demand that female athletes be celebrated as amazing, unprecedented superstars whether they win or lose. Advocates for gender equality in sports don’t want fair market competition based on customer preference, but to bully and coerce the sports industry to devote as much airtime as men’s sports to indifferent viewers. Male soccer fans who don’t like women’s soccer are sexist — that was the conclusion of a 2021 study at the University of Durham in the United Kingdom. Thus the demand that “change starts with more media coverage,” according to attendees at the 2022 SportsPro’s OTT Summit USA.

When male sports players make big mistakes, they are endlessly ridiculed — ever heard of Bill Buckner, Garo Yepremian, or Scott Norwood? Rapinoe, Biles, and Osaka are instead celebrated even more for underperforming, as if failure is itself a feminist victory. As Hirschauer notes, feminists inhabit an “alternative universe” of professional athletics: Rapinoe once asserted that WNBA point guard Sue Bird — who averaged 7.8 points per game in her career — had “like, arguably the best career that anyone has ever had in the history of any sport ever.”

A Controversy that Proves the Point

I once worked in a building with a large sign titled “Ten Ways to Empower Women in the Workplace” conspicuously placed directly outside the cafeteria, so that hundreds of employees would see it every day. Some of the suggestions amounted to little more than simply being respectful and professional to women (no harm in that!). But others (like encouraging women to “be themselves” or empowering them to “speak up”) implicitly communicated the need for men to exhibit deference to members of the opposite sex, as if male employees must treat their female colleagues with kid gloves in case they hurt their feelings or damage their confidence.

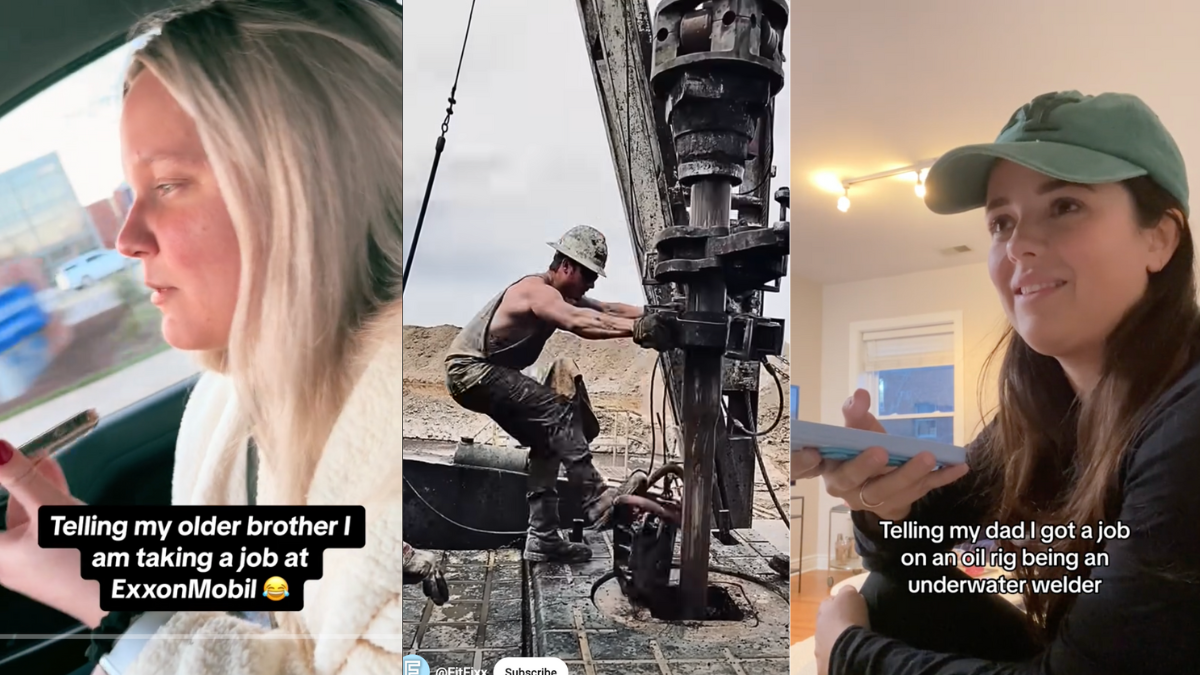

That sign itself was a symbol of an unspoken assumption today: Women must be recognized as the same as men, except they require special treatment that acknowledges and respects their inherent differences from men. Women are just as resilient as men, except when they need to be especially encouraged. They are just as fearless and strong as men, except they are grossly underrepresented in all the most dangerous and physically strenuous jobs. They are just as professionally flexible as men, except when they are pregnant or nursing.

My point is not that women can’t have great professional success, demonstrate remarkable resiliency, or exemplify tremendous courage. Of course, they have done, and do, all these things. Nor is it that female employees shouldn’t be given paid parental leave, nursing rooms, and other benefits to honor their role as mothers (they should be). But the louder feminists assert that they want equal treatment in all things — even in those places where their biological, psychological, and emotional differences are most saliently obvious — the more risible the argument becomes.

Hesse’s calumnies against male critics of Swift (while seemingly oblivious to years of thrown shade against Kelce for being overrated, thus vitiating her double-standard thesis) prove the point. Moreover, the very fact that The Washington Post has a feminist female gender columnist, and no male equivalent to present counterpoint, seems to as well, no?