Not even Jeeves could save Bertie this time. The censors have come for P.G. Wodehouse, the greatest comic author of the last century. His publisher is rewriting some of his books, including books from the iconic “Jeeves and Wooster” series, to excise content deemed offensive to modern readers.

I feared this was coming, but hoped the new woke censors would overlook Wodehouse — after all, such miserable scolds might not read light comedy. But it seems enough of them work in publishing that someone noticed Wodehouse’s transgressions against pure language and thought, and persuaded Penguin Random House to subject his writing to posthumous sanitation.

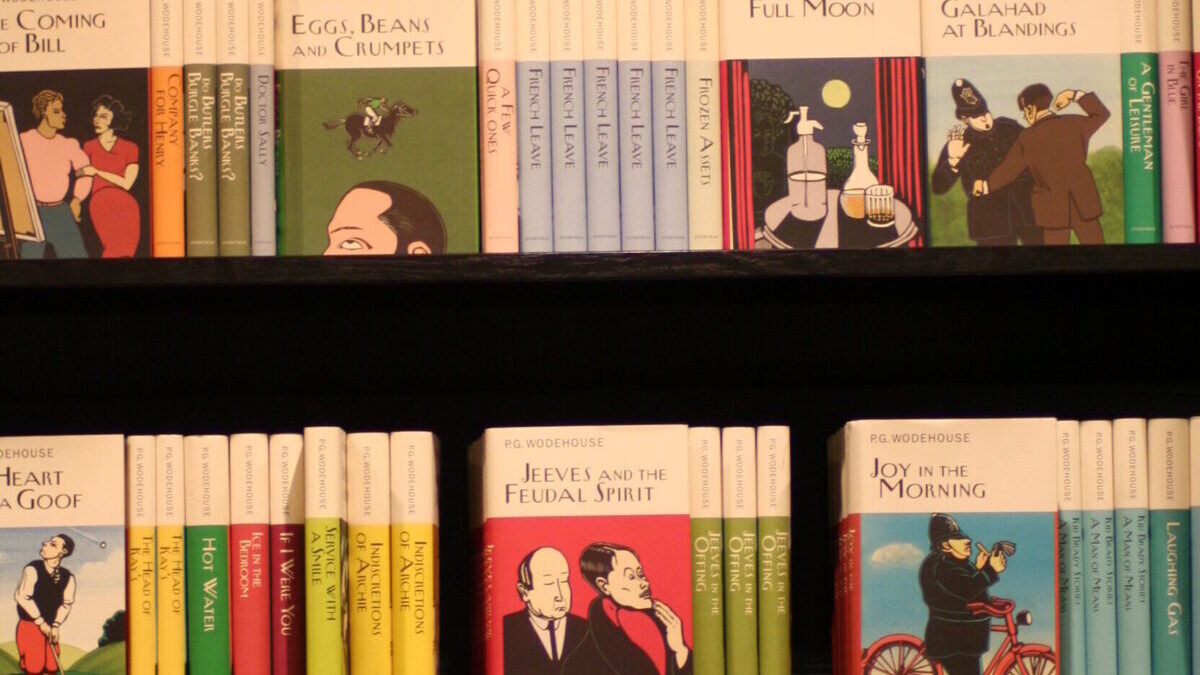

Fortunately, I’ve already got the complete Wodehouse collection. They can’t rewrite what’s on my shelves — though they might eventually take a page from another classic dystopia and try to burn books. Regardless of their approach, woke censors are always convinced they are in the right as they try to sanitize the work of the past. And in this case, they might seem to have a bit of a point. After all, why shouldn’t we get rid of the awkwardness and offense of Bertie Wooster dropping the n-word?

The immediate problem with this is that the woke coterie in the publishing industry has shown no ability to stick to just a little bit of censorship. The Wodehouse rewrites have reportedly already gone beyond just purging the worst racial slurs, and there is no reason to think the censors will stop anytime soon. Just look at what they did to “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” and the rest of Roald Dahl’s works, which they clumsily rewrote to purge anything offensive to hyper-sensitive scolds. It is the nature of wokeness to always seek new sources of offense, and so the woke will always find more thought crimes to erase.

Works Provoke Discussion of Race

Wodehouse’s works should also be left as-is for reasons that even the woke censors would approve of if they were honest and consistent. Wodehouse’s books provide precisely the sort of opportunity for an honest discussion about the history of racism that they claim to want.

For instance, Wodehouse provides an apt illustration of how the n-word, as we now refer to it, used to be less offensive. John McWhorter has chronicled how it has gone from its initial use as “a neutral descriptor” to a “slur” to an “unspeakable obscenity” that is now the closest thing to blasphemy in the English language. During this process, there was “a transitional period” as the word went from normal to impolite to taboo. Wodehouse wrote during this time, and while there are only a few racial slurs in Wodehouse’s nearly 100 published books, his handling of them was usually used to develop his characters.

Thus, In “Thank You, Jeeves,” both Bertie Wooster and his friend Chuffy drop the n-word casually, but without meaning any harm by it. This was entirely in keeping with the norms of 1934, when the book was published. It confirms Bertie as a little insensitive (and certainly less polished than his valet Jeeves), but does not reveal any real racial malice in him. A similar example is found in “Psmith, Journalist,” in which Psmith’s character as a young man who is loquaciously polite and amiable even to his foes extends to using the descriptor “colored gentleman” rather than something cruder.

The ugliest use of a racial slur in Wodehouse is probably in the school story “The White Feather,” published in 1907. This obscure early work was written while Wodehouse was finding his voice as an author, and is only really of interest to someone who is studying his development or is determined to read everything he ever published.

It is jarring to modern readers to have the hero derisively think of a boxing opponent with the n-word. Yet the early Wodehouse is still nuanced and surprisingly true to life, noting that in British public schools of the time (what Americans would now call private schools), this was used as “a term covering every variety of shade from ebony to light lemon.” It was, in short, a generic and mildly derogatory term for those who were non-white (or even just non-English). It might be a bit racist, but it was not necessarily virulently so, and Wodehouse was well aware of the difference.

Nuanced Usage

For example, in the “Kid Brady” stories, published around the same time, he tells of the eponymous hero meeting a black boxer: “The Kid shook hands with the stranger. Being British-born, he had none of the American’s inherited dislike of the colored.” In this line, Wodehouse is almost certainly speaking for himself as well, a premise that is further supported by “The Luck Stone,” a schoolboy adventure story from the same period, in which Wodehouse featured a popular and intelligent (if comically verbose) “dark-skinned” student from India. Wodehouse’s characters, and the author himself, were not above all racial stereotypes and tropes, but there is little animus in them.

Of course, all of this discussion over race is to make much of a small portion of his writing. Race was not a significant theme in Wodehouse’s work, but when it does come up his treatment of it is deliberate and much more nuanced than those expunging his work give him credit for. Better and more learned editors would have taken the opportunity to provide brief, insightful editor’s notes on these points in new editions of the relevant Wodehouse books. Readers could have learned a little about history, racism, and language before moving on to the laughter that Wodehouse elicits.

But contrary to their claims, the current race-obsessed woke scolds don’t really want to learn from the past nor study it with any real care. They would rather denounce and erase the past than try to understand it. Learning from the past implies we have something to learn, and their preferred posture toward both past and present is that of a lecturer taking dim and recalcitrant students to task.

If only we had an all-knowing valet to engineer a way out of this.